Arpana Caur: Time Refreshed

IN 1981, HAVING sold a few paintings, artist Arpana Caur, then aged 27, plunged into the world of Indian miniature art. Money she'd earned, she spent on books on the subject, and when offered a barter, she readily accepted. A book for a painting of her own seemed like a reasonable exchange. It was through such a deal that she acquired a volume of Court Paintings of India 16th-19th Centuries by Pratapaditya Pal, published by Navin Kumar. She also bought several books by BN Goswami, an authority on Pahari paintings.

With time, as she sold more of her own work, she began buying original miniature art. The boom in the Indian art market that began in the late 1980s helped. In the early 1990s, a collector offered to exchange his prized Sikh miniatures for one work from each of her five series. Other art dealers made similar exchanges with her. At the same time, she continued to buy.

Today, her 250 miniatures make up the collection at the free, Museum of Miniatures (now online, thanks to the efforts of the Google Cultural Institute) housed at the Academy of Fine Arts and Literature, Delhi, that was founded by Caur's mother, noted Punjabi writer, Ajeet Caur in 1975. The Academy, which is a cultural centre, also has a Museum of Folk and Tribal art, as well as a collection of Caur's own work.

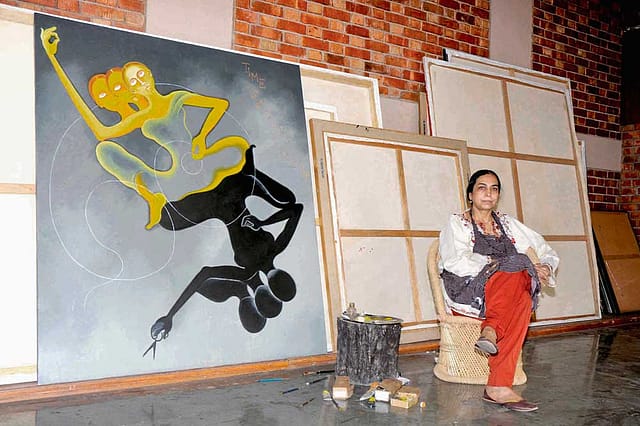

All this is testament to the passion and deep humanism that Caur shares with her mother, qualities that also animate her art. The leafy environs of the National Gallery of Modern Art in Bengaluru are host to an ongoing retrospective of Arpana Caur's works spanning four decades, including 25 large oils on canvas from the Swaraj Art Archive, Noida, as well as 17 works from the artist's mother's collection.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The rounded figures of her large canvases leap out, crouch in corners, swim across dark expanses, or lie motionless. Some have transcended time, while others play their part, caught between earth and sky, reality and longing. And then are those who mark time and destiny, like the female Fates of Greek myth.

It is easy to see the effects of Indian miniature art on Caur's canvases—from the use of gem-like colours, simple figuration devoid of Western camera realism and the absence of light and shade to the stylistic treatment of trees and water bodies and the use of curved horizons. Deer, tigers and peacocks reminiscent of those of the Pahari school leap across or fall off her canvases. Persian and Rajasthani miniatures that depict horses or elephants containing multitudes within, inspired the imagery of several human figures within a single figure. In the early 1980s, Caur took a leaf from Punjab miniatures that portrayed stark white architecture with the fourth wall sliced away to present unusual perspectives.

Even the depiction of water using swirls in Water Weaver—a dark canvas in which a figure in a foreground weaves a watery blanket to douse the flames of communal hatred that have ravaged a city in the background—takes from miniature tradition. She pays homage to folk art like Warli, Madhubani and Gond art and artists, and there are glimpses of her childhood steeped in Punjabi culture, folk literature, and her mother's writings, in her art.

"We've inherited all these things. How can you show reverence for traditions you have inherited? By incorporating its elements in your work," she says. Her early canvases were dominated by large sculptural figures, but it wasn't long before she began to look beyond the figure to the space around.

"I can't get away from the figure; it flows in the blood. But 10 to 15 years ago, I realised that unless you introduce an element of abstraction, your figuration will not have mystery," she says, speaking admiringly of the Chola bronzes that combine simplification and abstraction.

Despite the borrowings and references to tradition, her art is firmly contemporary and replete with startling iconic imagery that is very much her own. Scissors stand for time, knives and weapons for threats and danger, matkaas or mud pots for the mortal body, and a fallen leaf for nature. Feet transcend time, epitomising our twin desires to be both rooted and to fly. Her art speaks directly with moving sincerity, reminding us of our morality, mortality, and oft-forgotten humanism, addressing socio-economic inequality and our growing distance from nature. 'My art may be abstract figuration, it might talk about contemporary issues, but my form of expression, the imagery and style, is very Indian,' writes Caur in the catalogue of work. In the way she has arrived at a contemporary Indian idiom that pays homage to folk artistic and narrative traditions, she shares a kinship with post-Independence artists such as Nandalal Bose, Jamini Roy, KG Subramanyan and MF Husain.

It was Husain who first selected a young Arpana Caur in 1974 to participate in a group show from a pool of applicants. A few years later in 1980, he bought her painting on the rape of Maya Tyagi by policemen titled Custodians of the Law.

For Caur, there are some paintings that she has literally "painted out of her system". Many of her early works are such cathartic expressions of pain. Outside the Blue Gallery, from the early 1970s is a rude awakening to the divide between the haves and have-nots. The 'World Goes On' series was born of the lived experience of the brutal violence against Sikhs in 1984 following the assassination of Indira Gandhi. In the series titled Widows of Vrindaban, she attempts to make sense of the dismal state of widows in a town ironically fabled for the romance of Krishna and Radha.

Some themes continue to inspire her, such as the Day and Night series, a philosophical rumination on time, and the Love Beyond Measure series, which is based on an ancient folk tale from Sindh and Punjab. Sohni, a potter born in Aknoor 500 years ago, and Mahiwal, a visiting trader from the East, fall in love. Her family disapproves and arranges her marriage to a potter. Mahiwal sets up home across the river from Sohni's marital home and Sohni crosses the river every night using an earthen pot to stay afloat, which she hides near the river. When her sister-in-law discovers her secret, she quietly replaces the pot with one of unbaked clay. That night, Sohni drowns in her attempt to reach Mahiwal. But Mahiwal jumps in to join her, and they are united in death. The story is tragic and poignant, but also speaks of courage to go beyond and often against people's expectations.

Caur has several canvases inspired by the Buddha, Guru Nanak, Kabir, the mystical bauls, yogis and yoginis. Much of the meaning in Caur's art lies between dualities, both thematic and visual. In wrestling with themes such as day and night, life and death, rootedness and flight, apathy and empathy, she pits the organic against the linear; a deer, a representation of innocence and nature, juxtaposed with an arrow, a symbol of man's capacity for violence.

Ultimately, the creative process is a mysterious one. "You don't create, you are created in the process of painting," says Caur. "With each painting, you plumb new depths, explore previously unexplored areas of the self. It is like stretching a rubber band that has no limits." n

('Four Decades: A Painter's Journey' will run till December 4th, National Gallery of Modern Art, Bengaluru)