Pakistan’s Alien Roots

The Islamic revivalism that birthed the nation was decidedly Middle Eastern in spirit

J Sai Deepak

J Sai Deepak

J Sai Deepak

J Sai Deepak

|

24 Feb, 2023

|

24 Feb, 2023

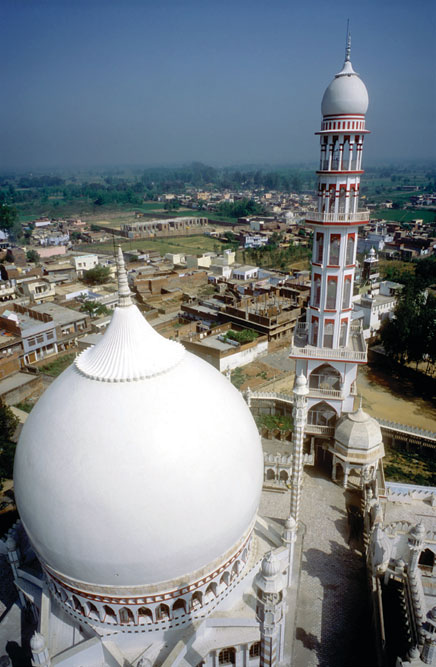

/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Pakistan1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

IN MY FIRST BOOK, India That Is Bharat, I introduced the concept of Middle Eastern coloniality and briefly touched upon its concrete manifestation in the history of Bharat, namely the birth of the idea of Pakistan. I took the view that the creation of Pakistan must be seen as part of Middle Eastern coloniality’s long, troubled and continuing encounter/interaction with the Indic civilisation. The violent creation of Pakistan has been the subject of tomes of literature. So, to avoid being redundant, I intend to view it through the prism of Middle Eastern coloniality to examine its impact on the shaping of Bharat, especially its legal and constitutional infrastructure.

In popular discourse, the Partition of Bengal in 1905 on religious lines by the British is credited with sowing the seeds of the idea of Pakistan. This has created the false impression of communal harmony having existed between Hindus and Muslims prior to the employment of the so-called divide and rule policy by the British in 1905. While British motivations behind the Partition of Bengal and their subsequent hand in nurturing the idea of Pakistan must and will be examined in some detail, an exclusive focus on British machinations creates the erroneous notion of Hindus and Muslims being equal victims of British rule, drawing attention away from express attempts to restore Islamic rule over Bharat. It bears noting that an Anglocentric approach, which gives Middle Eastern coloniality a free pass in the context of Bharat’s Partition, is largely a product of the postcolonial school; this, therefore, reinforces the need for a decolonial approach to Bharat’s history to prevent the sugar-coating of facts with generous dollops of postcolonial secularisation.

To understand the larger backdrop against which the pan-Islamic movements of the 1800s—such as the lesser-known Faraizi Movement (which was largely limited to Eastern Bengal) and the better-known Wahhabi Movement (which started in Delhi and spread to different parts of Bharat)—were set, we must travel further back in time. A clear understanding of the origins, nature, inspiration and aims of both the movements and their successors is called for in order to grasp the full extent of the psychology and pathology of Middle Eastern coloniality. I have consciously chosen to write about these movements since their profound impact on the revival of Middle Eastern coloniality’s quest to regain control over Bharat is rarely mentioned, let alone discussed, in contemporary discourse, out of a misplaced sense of political correctness, aka ‘Indian secularism’. This is despite the Indian Wahhabi Movement’s manifest and critical contribution to the laying of a fertile ground for Islamism not just in undivided Bharat but also in the larger Indian subcontinent, the impact of which is still being felt in one way or another. Perhaps there is discomfiture in certain ‘secular’ quarters in recognising the fact that the Wahhabi mindset had and continues to have a strong Indian base.

In the absence of this big picture, the Bharatiya mind, which is currently buried deep under three layers of coloniality— European, Middle Eastern and Nehruvian Marxist/postcolonial—will continue to consume popular, comforting and infantile fictions. One such fiction is the existence of a ‘Ganga–Jamuni tehzeeb’, the much-touted composite cultural creature that is the supposed product of a syncretic relationship between Hinduism and Islam, creating the so-called unique Indian Islam. To precisely overcome these perception barriers so that facts finally have a chance to breathe and shape the truth, I will touch upon the circumstances which led to the rise of pan-Islamic movements in Bharat. While there is a larger and troubled history of Islam in Bharat which warrants examination, I have chosen to focus on the most proximal cause of the rise of such movements—the decline of the Mughal empire—which had a direct bearing on the Partition of Bharat, so as to assess the latter’s impact, if any, on the making of independent Bharat’s Constitution.

The simultaneous decline of two Islamic empires was a cause for concern among Muslim intellectuals of the time. This churn threw up two individuals of consequence—Muhammad Ibn Abd Al-Wahhab in Central Arabia and Shah Waliullah Dehlawi in Bharat. According to them, Islam was due for a ‘reformation’, which meant going back to its ‘pristine form’ without the heresies and the deviances that had crept into its practice by virtue of its contact with the infidels

The other reason for choosing this period of history is that the age of monarchies and dynasties was gradually drawing to a close and the world was being reshaped on European/Western lines. Middle Eastern coloniality too had to grudgingly adapt to these changed circumstances, which translated to a greater involvement of the Muslim masses (the Ajlafs and Arzals, typically of Indian ancestry) in politics, which was hitherto the primary or perhaps even the exclusive preserve of the Muslim nobility and religious elites (the Ashrafs, who claimed non-Indian ancestry). For the purposes of this discussion, I have drawn primarily from the works of R.C. Majumdar, W.W. Hunter, H.V. Seshadri, Qeyamuddin Ahmad, Muin-ud-Din Ahmad Khan, Girish Chandra Pandey, Maulana Syed Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi, Barbara Metcalf and other authors on the subject, including researchers and academics of Pakistani origin, such as Ayesha Jalal, Sana Haroon and Yusuf Abbasi.

The disintegration of the Mughal empire, which began under Aurangzeb, largely due to his disastrous campaign in the Deccan (‘the graveyard of the Mughal empire’) against the Marathas and his murderous crusade against the Sikh gurus, was expedited after his death, thereby loosening the grip of Islam over Bharat significantly. The clearest sign of the terminal decline of the Mughal empire was its Balkanisation through the establishment of the Asaf Jahi dynasty in the Deccan (also known as the Nizam ul- Mulk of Hyderabad) in 1713, the Awadh dynasty under Nawab Sadat Ali Khan (Burhan ul-Mulk) in 1723 and the Bengal dynasty under Nawab Aliwardi Khan in 1740. To add to it, Nadir Shah’s sack of Delhi in 1739 had rendered the Mughal empire hollow and exposed its own decrepitude. In less than 200 years of Babur’s victory in the First Battle of Panipat in 1526, Mughal influence was largely limited to Delhi as a result of the growing power of the Marathas, the Jats, the Sikhs and the English. The Battles of Plassey (1757) and Buxar (1764), in particular, established the English as an aspiring contender for religio-political supremacy over Bharat. It was around then that the Ottoman empire too saw a general decline, with its inability to keep pace with the Habsburg and Russian empires becoming more evident.

The simultaneous decline of two avowedly Islamic empires was a cause for concern among Muslim intellectuals of the time. This churn threw up two individuals of consequence— Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792) in central Arabia and Shah Waliullah Dehlawi (1703–1762) in Bharat, both of whom attributed the decline of their respective Muslim empires to the corrosion of their religio-social foundations. Therefore, according to them, Islam was due for a ‘Reformation’, which meant going back to its ‘pristine form’ without the heresies and the deviances that had crept into its practice by virtue of its contact with the infidels. Where Christian Reformation meant going back to the basics by undoing the Catholic Church’s monopoly over the ‘true faith’, Islamic Reformation meant recreating Islam, also ‘the true faith’, as it existed during the Islamic Prophet’s life and time.

According to Qeyamuddin Ahmad, Wahhabis are not essentially different from the rest of the Muslims. However, they place greater emphasis on the following aspects, and here I quote Ahmad:

Monotheism: God is self-existent and the Creator of all other beings. He is unequalled in his attributes. Spiritual eminence and salvation consist in strict adherence to the commands of God as given in the Quran and laid down in the Shariat and not in developing mystical feelings of communion and mingling in His feeling.

Ijtehad: The Wahhabis admit the right of ‘interpretation’ as given to the Muslims and stress the desirability of exercising this right. They hold that the followers of the four great Imams have, in effect, given up this right. Abdul Wahab wrote several treatises on the subject criticising the advocates of slavish imitation.

Intercession: The Wahhabis do not believe in the theory of intercession or prayer on another’s behalf, by intermediaries that might be of saintly eminence and hence supposedly nearer to God. Passive belief in the principles of Islam is decidedly insufficient.

Innovation: The Wahhabis condemn and oppose many of the existing religious and social practices for which there is no precedent or justification in the Shariat. Prominent among these are tomb worship, exaggerated veneration of Pirs, excessive dowries in marriages, the general show of pomp on festive occasions such as circumcision and Milad (celebration of the Islamic Prophet’s birthday) and prohibition of widow-remarriages.

When these four salient features are read together, especially in view of the prohibition on innovation, it becomes clear that the room for ijtehad is limited since it permits only the Quran and the Hadith, as opposed to later legal treatises on Islam, to be treated as authorities so that life in contemporary times may be lived as close as possible to the lives of the earliest followers of Islam. This, as stated earlier, is to preserve the ‘purity’ of an Islamic life.

Wahhab’s ideas influenced later Islamic movements in Bharat founded by religious leaders who had travelled to Arabia during Wahhab’s lifetime or had been exposed to his teachings during their Haj pilgrimage. However, Dehlawi may be treated as the more direct progenitor of Islamic revivalism in the Bharatiya subcontinent and—incorrectly, or perhaps for the sake of convenience—this revivalism has been dubbed as Indian Wahhabism. While Wahhab’s movement was named after him and his followers were called Wahhabis, the movement started by Dehlawi, which was more systematically established by his spiritual successor, Syed Ahmad Shahid Barelvi, was called the Tariqa-i-Muhammadiyyah, or the Path of Muhammad, and its followers were initially called Muhammadis. However, the latter movement too was branded ‘Wahhabi’ later on, in view of its similarities with the more prominent Middle Eastern variant.

Some scholars have attributed the similarities between Wahhab’s and Dehlawi’s views to the fact that both were exposed to the works of the thirteenth-century Sunni Islamic scholar Ibn Taymiyyah as part of their education on the Hadith in Medina around the same period. In fact, Wahhab and Dehlawi may have been contemporary students of Hadith in Medina, which could explain the similarities in their hard-line positions. Among Taymiyyah’s primary contributions to Islamic jurisprudence was his pronouncement that jihad could be waged against Muslim rulers too if they did not live as true Muslims and by the Shariat. This fatwa was issued in the context of fighting Muslim Mongol rulers when the Muslims of the Levant were unsure if jihad was permitted in Islam against co-religionists. Taymiyyah’s views themselves were mostly drawn from the wider Hanbali Movement in Baghdad and Syria, which started in the ninth century. This movement insisted on literal acceptance of the Hadith, avoidance of theology, repression of popular Sufi practices and intense criticism of corrupt (read ‘un-Islamic’) Muslim states. Therefore, it could be said that Wahhab and Dehlawi were proponents of Taymiyyah’s Hanbalist views, which makes Wahhabism a misnomer, and Taymiyyism or Hanbalism the more accurate term. However, since the literature on the subject refers to the movement as Wahhabism, and in view of its more recognised association with Wahhab, I too shall do the same in the interest of literary consistency and recall value.

Coming to Islamic revivalism in the Bharatiya subcontinent, Dehlawi stands out as much for his antecedents as he does for his investment in and contribution to the cause, which, as we shall see, influenced Muslim thought in the subcontinent for generations to come. This includes successor ‘reform’ Sunni movements such as the Ahl-i-Hadith, Ahl-i-Quran, Deobandi, Barelvi, Nadwah, Aligarh, Tablighi and Pakistan Movement. Dehlawi was the son of Shah Abdul Rahim, one of the founders of Madrasah-i-Rahimiyah in Delhi and a prominent Islamic scholar who was part of the committee appointed by Aurangzeb to compile the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri. This compilation remains the go-to commentary till date on the Shariat for Sunni Muslims of the Bharatiya subcontinent.

Coming to Islamic revivalism in the Bharatiya subcontinent, Dehlawi stands out as much for his antecedents as he does for his investment in and contribution to the cause, which influenced Muslim thought in the subcontinent for generations to come. This includes successor ‘reform’ Sunni movements such as the Deobandi, Tablighi and Pakistan movement

Dehlawi was trained by his father in Islamic studies before he (Dehlawi) left for Arabia in 1730 for his higher education. After his return to Delhi in 1732, he wrote prolifically in Persian and Arabic, and engaged in spreading his knowledge of Islam. In the words of Saiyid Athar Abbas Rizvi, the following was Dehlawi’s conception of Islam:

“The reason which prompted Allah to create the Islamic community originally was, according to Shah, mainly a political one. Allah wished that no religion superior to Islam should exist on earth and that Islamic law including those regarding different forms of punishment, should be adhered to wherever people lived a communal life. In this regard, he stated that the chief reason for fixing the blood-money for killing an infidel at half that of killing a Muslim was necessary in order to firmly establish the superiority of the latter; moreover, the slaughter of infidels, diminished evil amongst Muslims.”

In his work Tafhimat-i Ilahiyya, addressing Muslim rulers of his time, Dehlawi’s fervent exhortation to them on their duty to preserve Islamic purity in a multi-religious society was as follows:

“Oh Kings! Mala’a’la’ urges you to draw your swords and not put them back in their sheaths again until Allah has separated the Muslims from the polytheists and the rebellious Kafirs and the sinners are made absolutely feeble and helpless.”

It is no wonder then that Dehlawi, as part of his teachings, exhorted Muslims of the subcontinent not to integrate into society, since contact with Hindus would contaminate their Islamic purity. He urged them to see themselves as part of the global ummah. To this end, although he himself was a sanad-holding Sunni Sufi of the Naqshbandiyah Order, Dehlawi wanted Muslims of this part of the world to rid themselves of bida’a, i.e. Hindu influenced Sufi practices and mores which tended to be retained by converts to Islam from the Hindu fold. In other words, only that version of Sufism which was rooted in the Quran and the Hadith was the ‘right’ one since it was consistent with Islam; non-Islamic and external influences were treated as un-Islamic. Here, Islamic refers to Sunni Islam, as Dehlawi had no love lost for the influence of Shias either on the Muslim identity.

He mandated that Muslims of the subcontinent follow the customs and mores of the early Arab Muslims since they were the immediate followers of the Islamic Prophet. These were his views on the subject:

“I hail from a foreign country. My forebears came to India as emigrants. I am proud of my Arab origin and my knowledge of Arabic, for both of these bring a person close to ‘the sayyid (master) of the Ancients and the Moderns’, ‘the most excellent of the prophets sent by God’ and ‘the pride of the whole creation’. In gratitude for this great favour I ought to conform to the habits and customs of the early Arabs and the Prophet himself as much as I can, and to abstain from the customs of the Turks (‘ajam’) and the habits of the Indians.”

Clearly, birth in Bharat alone does not make someone Bharatiya, since more than race or ethnicity, it is the consciousness of being Bharatiya that matters. As long as the consciousness refuses to embrace the Indic element, it remains alien, notwithstanding claims of accrual of nativity by birth. Dehlawi’s commitment to Middle Eastern consciousness is clear from his will, in which he called upon his heirs to give up the customs of pre-Islamic Arabs and the hunud, which, of course, was a reference to Hindus.

(This is an edited excerpt from India, Bharat and Pakistan: The Constitutional Journey of a Sandwiched Civilisation by J Sai Deepak)

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

On Being Young Surya San

Why Are Children Still Dying of Rabies in India? V Shoba

India holds the upper hand as hostilities with Pakistan end Rajeev Deshpande