The Culture of Caste

The sociology of violence in popular cinema

/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Caste1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

JAI BHIM IS LIGHT. Jai Bhim is love. Jai Bhim is a path from darkness to light. Jai Bhim is the tear drop of millions of people.” With these words, ascribed to a Marathi poet and scripted on the screen as the lights flicker on, TJ Gnanavel’s Jai Bhim (2021) draws to a close. Tamil cinema, if Jai Bhim and some other recent films are anything to go by, has left Bollywood and even Marathi cinema far behind in its treatment of the vexed question of caste domination, caste inequality and a landscape not only of shifting caste alliances but of what may be called the cultures of caste. If no one can pretend to have mastered the intricacies of caste in India, modern Tamil cinema has at least carved out a distinct though scarcely complete roadmap to the peculiarities and politics of caste in Tamil Nadu—and it does so with the awareness of how the language of cinema may be deployed to create new sympathies and generate the vicarious experience of the sentiments and sensations of someone else.

It is characteristic of the contemporary writing on caste, and indeed of so much of the commentary on Jai Bhim, that it has become nearly impossible for many to think of caste except in relation to violence. Activists, advocates of human rights and others who are rightly alarmed by the increasing brutalisation of everyday life in India have been drawing attention for decades to “caste atrocities”. There is a growing literature on caste wars, and sexual violence unleashed on lower-caste women is increasingly being reported from all corners of India, making its way into the footnotes in a legion of reports issued by government agencies, “concerned academics”, and non-governmental organisations. Many commentators have, of course, a richer and more nuanced understanding of the violence to which lower castes are subjected, considering the untold number of ways in which notions of caste hierarchy insinuate themselves into the transactions that comprise everyday life and the myriad ways in which lower-caste people are stripped of their dignity. What is remarkable about the treatment of caste in Tamil cinema, taking Jai Bhim as my illustration, is that it makes us aware of caste as more than a narrative about violence—even if the films under discussion offer unflinching portrayals of the violence that caste inspires. Viewers have understandably recoiled at scenes of police brutality in Karnan (2021) and especially Jai Bhim, but it requires looking beyond this violence to come to grips with the various idioms in which the cultures and community of caste come to the fore.

What is remarkable about the treatment of caste in Tamil cinema, taking Jai Bhim as my illustration, is that it makes us aware of caste as more than a narrative about violence—even if the film offers unflinching portrayals of the violence that caste inspires. Viewers have understandably recoiled at scenes of police brutality but it requires looking beyond this violence to come to grips with the various idioms in which the cultures and community of caste come to the fore

The storyline of Jai Bhim is easily understood. A tribal woman from the Irula community, Sengani (Lijomol Jose) is on a quest to find her husband, Rajakannu (Manikandan), who has been falsely implicated in a theft case and is alleged to have escaped along with two other men, one his brother, from a police station where they were being tortured in an attempt to extract confessions from them. The three men remain missing and Sengani, who is pregnant with her second child, is beside herself with grief and anxiety. Owing to the intercession by a teacher who has been working with the community, Sengani is able to enlist the services of a lawyer, Chandru (Suriya), who advocates for the rights of the tribals and decides to file a habeas corpus writ in court. Despite efforts by the state prosecutor to have the writ thrown out, it is admitted: the body must be produced. And yet it cannot be, since Rajakannu is among the thousands in India who die in police custody every year. Sengani rejects the entreaties by the police to accept compensation and is determined to seek justice for her husband. The elaborate case built by the police, designed to project Irula men as “habitual offenders” who are accustomed to a life of theft unravels with each sitting of the court until the policemen responsible for Rajakannu’s custodial death are finally taken into police custody and Sengani is inter alia given a gift of land as recompense.

Thus far, it may seem that Jai Bhim conforms to many elements of the mainstream cinema and is accepting of the mythic structuring of good versus evil in the form of a wholly adversarial and indeed violent relationship between the state and its most downtrodden subjects. The film appears to endorse a conventional politics of representation: whatever the self-respect with which Sengani wages her quest for justice, Chandru becomes the voice for the voiceless, yet the latest instantiation of the omnipresent hero who saves the day for the oppressed. As Marx famously put it in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, “They cannot represent themselves; they must be represented.” The feminist and the purportedly radical critic might further object that the film—even as it vindicates Sengani and gives succour to those who stand by the idea that the law is not merely an instrument of the powerful—embraces a savarna, patriarchal and bourgeois conception of justice. In this respect, the criticisms of Jai Bhim can be entirely anticipated: the film puts forward an idealist conception of the Indian judiciary, is rather oblivious to the deep structuring of the violence of the state in which nearly all institutions are implicated, and subtly if unself-consciously embodies the very upper-caste world of privilege that it apparently seeks to put into question. The upper-caste status of the men, and it is almost all men who, for instance, work the court system, whether as judges, advocates or prosecutors, is never mentioned but only implied—and this because, as the French structuralist Roland Barthes noted, the privileged in any society do not have to be named, they are the ex-nominated and their privilege is part of the common sense of a society.

It is doubtless the case that the record of the Indian judiciary has been far from spotless in its advocacy of the rights of those suffering from caste oppression and the sexual violence visited upon women who seek to question caste norms or patriarchal authority. The 1972 sexual assault case of Mathura, an orphaned minor Adivasi girl, and similarly the 1992 case of the lower-caste Bhanwari Devi who came from a family of potters come to mind. In both cases, the men charged with gangrape were acquitted: in the former case, the court declared that Mathura was evidently “habituated to sexual intercourse” and therefore could not have been raped, while Bhanwari’s tormentors were acquitted on the grounds that it was inconceivable that her husband could have watched passively while his wife was being gangraped. There have been a great many other cases from recent years which point only to the fact that the institutions of a society reflect to a great extent the norms to which the society subscribes, but nevertheless the infirmities of the Indian judicial system do not ipso facto become the grounds for supposing that the law is always in principle compromised and merely a conduit for further oppression. Indeed, what is ironically salient, even touching, about Jai Bhim where some of the violence may seem gratuitous and voyeuristic is its resolute refusal of the temptation to violence—the temptation, all too common, to suppose that the only way to check state power is through the recourse to arms. What is thus compelling about Jai Bhim is its self-awareness that even as one is called upon not to give up on the law as a way to curb the state’s instinct to be unaccountable in its use of power, it would be naïve not to recognise the immense reach of the state. Here, as in the case of a Scheduled Tribe such as the Irulas, this extends to the state’s power to effectively shape their very existence and identity. They bear neither identity nor ration cards; they have no land to their name; their names do not appear on any voters’ list: they may as well not exist, or that is how it appears to the haughty officer before whom a group of Irula men appear as humble suppliants only to be told that they cannot be issued a community certificate.

The upper-caste status of the men, and it is almost all men who, for instance, work the court system, whether as judges, advocates or prosecutors, is never mentioned but only implied—and this because, as the French structuralist Roland Barthes noted, the privileged in any society do not have to be named, they are the ex-nominated and their privilege is part of the common sense of a society

Jai Bhim’s beginning, split in half by the credits that roll through the frames, gestures at the various registers of caste as it operates in everyday life. One is tempted to say that the crispness of the opening scene nearly echoes the selection process at Auschwitz, the gate to which bore the ominous sign, “Arbeit Macht Frei” (“Work Sets You Free”), and where upon arrival the fit were sent to the labour camp and others were at once condemned to the gas chamber. As men emerge from a prison compound, each is asked his caste: Koravars, Irulas and Ottars—backward communities all—are retained, while Gounders, Mudaliars and Vanniyars are among the backward yet dominant castes who are released to their families. Why, asks one young police recruit of another policeman as he looks at those held back, “Has no one come to receive them? Are they orphans?” “You could say that,” replies the other with a faint smile on his face. Those from the powerless backward communities are herded into a bus; their few relatives wail and plead for their lives. “I am as good as dead, Dad, the cops won’t let me live anymore, take care of my family.” So says one young man on the bus, his face set behind the window grill. The bus rolls away; the young man’s father, an old man with flowing white hair, takes some haltering steps after it, his outstretched hands pleading for his son’s life; the scene dissolves into a raised fist, the banner of revolt of the Ambedkarites; and around the fist the title forms in white against a darkened background: Jai Bhim!

The film then cuts to a pastoral background of verdant green, rolling hills and neatly laid paddy fields. A girl, two men, a woman: a family of rat-catchers, skilled at smoking out the rats who scurry down the tunnels and into the hands of the rat-catchers. Rats are the daily food of the Irulas and the scourge of farmers who wish for a bountiful harvest. This is skilled work, since the rat-catcher must know the lay of the land and discern where the rats have built their tunnels. Sengani releases a baby rat, telling her irate husband: “Should we ease our hunger with that little thing?” Other men and women, also rat-catchers, come into the frame: this is an occupation-based caste community, one whose very work suggests just how far down they are in the hierarchy of caste. Besides being rat-catchers, they are snake-catchers, and they alone understand that some rats must be caught while others must be set at liberty, and the same holds true for snakes. Summoned to the home of the village pradhan (headman) to remove a snake, Rajakannu tells him as he bundles up the snake so he can release it into the fields, “God smeared venom on its fangs and it gets whacked everywhere it goes. If not for it, the town would be infested with rats.” Rajakannu has a flair for language, and here and there we have a visceral demonstration of the proverbial fondness of the rustic Indian for the proverb; and the cynic might even add that the filmmaker has unwittingly fallen prey to the cliched idea that the tribal lives in harmony with nature rather than seeing himself as the owner of all that he surveys. But there is something far more to all this since, as the film suggests, the pradhan—and modern man—cannot recognise a knowledge system other than his own. It is from the home of the pradhan that some jewels are lifted; the blame falls upon Rajakannu and male members of his family. And it is this which sets the rest of the story in motion, a story of the hunted and the hunters. And then it dawns on us that the men on the bus are but the rats on the fields—all caged, caged utterly.

One hundred fifty years ago, the colonial state passed the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871, amended to the Criminal Tribes Act, 1911 to encompass the Madras Presidency. Treated under its terms, entire communities or tribes were stigmatised as criminal; anyone born into such a tribe—the word was deployed here not in the precise sense of tribes as communities outside caste or averse to settled agriculture and prone to wandering around, but rather to designate certain caste communities as much as Muslims—was presumed to be a ‘born criminal’

The Irulas, however, are not just another Scheduled Tribe—at least not according to the colonial sociology of knowledge. One hundred fifty years ago, the colonial state passed the Criminal Tribes Act, 1871, amended to the Criminal Tribes Act, 1911 to encompass the Madras Presidency. Under its terms, entire communities or tribes were stigmatised as criminal; anyone born into such a tribe—the word was deployed here not in the precise sense of tribes as communities outside caste or averse to settled agriculture and prone to wandering around, but rather to designate certain caste communities as much as Muslims—was presumed to be a “born criminal”. Such supposed criminal castes and tribes were subjected to draconian regimes of registration, surveillance and control, and their members were assumed to be “addicted to the systematic commission of non-bailable offences”. A community so designated or “notified” had no judicial recourse and therefore there was little if anything to restrain the police from exercising sweeping powers against members of the said community. In the aftermath of Independence, the Criminal Tribes Act was repealed and various though not all communities were “denotified”; however, the Habitual Offenders Act was brought in its place in 1952, and the advocate general prosecuting on behalf of the state in Jai Bhim on several occasions contemptuously refers to Irulas as “habitual offenders”. That the film’s director, TJ Gnanavel, is sensitive to the history and implications of a language which delivers people into a world of social death is indicated all too clearly in a conversation that transpires between advocate Chandru and Natraj, a policeman assigned to assist Inspector General Perumalsamy in an inquiry into this case:

Chandru: What is your perception of this case?

Natraj: The [sub-inspector] made a lot of mistakes. Besides, it’s quite common for many in their caste to be convicted in theft cases.

Chandru: Is any caste devoid of thieves, Natraj? In yours, in mine… there are thieves in every caste. First, stop branding people based on their caste.

Natraj: Sorry, Sir, I didn’t mean it that way.

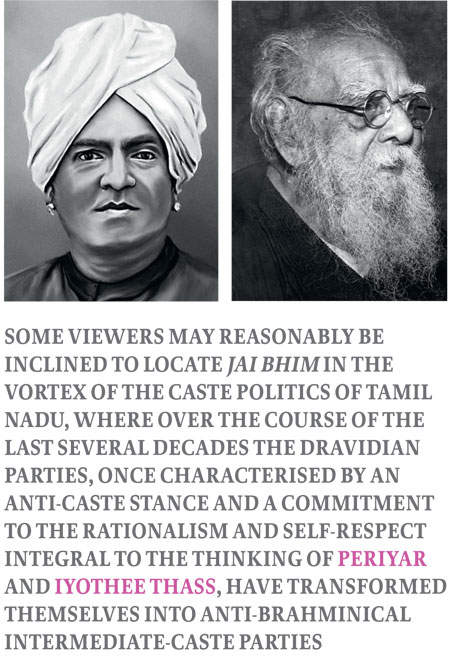

It may be that Natraj’s viewpoint is that of the savarna or upper caste and that it embodies the commonsense of that culture. That may be the most insidious part of the story of caste hierarchy. Some viewers may, however, reasonably be inclined to locate Jai Bhim in the vortex of the caste politics of Tamil Nadu, where over the course of the last several decades the Dravidian parties, once characterised by an anti-caste stance and a commitment to the rationalism and self-respect integral to the thinking of Periyar and Iyothee Thass, have transformed themselves into anti-Brahminical intermediate-caste parties. Let us recall the previously discussed opening scene, where some other backward communities are separated from the Vanniyars—itself a backward but nevertheless dominant caste that in the 1980s wreaked violence across the state in an attempt to secure recognition as a Most Backward Caste that would be entitled to enhanced reservations. Tamil Nadu’s chief minister, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam’s MK Stalin, has recently announced state support for a memorial in Villupuram to the memory of the Vanniyars who were killed in the 1987 clashes, but he also, only days after Jai Bhim was released on November 2nd, visited Irular and Narikuravar villages where he handed out land allotment certificates and ration cards to scores of residents. Villupuram is in the proximity to Cuddalore district where the real-life incident in 1993 after which Jai Bhim has been modelled took place. More to the point, Vanniyars have been vociferous in voicing their objection to the film, partly because a scene in the film hints at the affiliation of the sadistic Sub-Inspector Gurumoorthy, at whose hands Rajakannu dies, to the Vanniyar community.

It is all too tempting to subject Jai Bhim to such analysis; similarly, inescapable as is the sensation of the violence that the viewer experiences vicariously, the film is yet able to call forth a reading of caste that is not inextricably tied to the imagination of caste as merely the instrument of sanctioned violence. Jai Bhim’s cinematographer, SR Kathir, makes adept use of the camera to drive home this point. The policemen, especially when they are mercilessly pounding the Irular men in lockup in an effort to extract confessions from them, are shot in low angle: this makes them look gigantic, much larger than the emaciated tribal men who scatter to the corners of their prison cells like rats, but the effect of the shot is to fill the viewer with revulsion at the perpetrators of violence. Never does Gurumoorthy look so repulsive as when he looms large over them; yet, in another shot, precipitated by a scene where Gurumoorthy and two policemen working under him are cajoling Sengani to withdraw the case and accept compensation, Kathir places the camera overhead and the policemen seem diminished not only by the diminutive Sengani and her daughter, whose backs are to the camera, but by the unwieldy stash of files stacked on top of almirahs.

MK Stalin recently announced state support for a memorial in Villupuram to the memory of the Vanniyars who were killed in the 1987 clashes, but he also, only days after Jai Bhim was released on November 2nd, visited Irular and Narikuravar villages where he handed out land allotment certificates and ration cards to scores of residents. Villupuram is in the proximity to Cuddalore district where the real-life incident in 1993 after which Jai Bhim has been modelled took place

As I have argued, what in the last analysis is far more arresting, perhaps compelling, in Jai Bhim than the narrative of caste violence is its exploration of what I have termed the culture of caste and its implied invocation of caste as community. Throughout, notwithstanding the torments and hardships to which they are subjected, Irulas retain a keen sense of their self-respect and an awareness of what would be at stake in a capitulation to naked power. Let us confess, Rajakannu’s two companions urge, so that we may be spared this terrible chastisement, the pummelling of the flesh and the relentless attempts to rob us of our dignity. But Rajakannu knows better: our wounds will heal in a few days, he replies, but a false confession will stamp us as thieves for eternity. Caste oppresses but caste also permits one to constitute community. Ganavel takes you into the huts of the Irulas, gives you a glimpse of their mourning rites and transmutes caste as social structure into the castes of mind. Jai Bhim is not singularly alone among Tamil films in daring to probe the cultures of caste, but that is a story for another time.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Cover_Kumbh.jpg)

More Columns

The lament of a blue-suited social media platform Chindu Sreedharan

Pixxel launches India’s first private commercial satellite constellation V Shoba

What does the launch of a new political party with radical background mean for Punjab? Rahul Pandita