The Ideal Against the Political

The making—and the almost unmaking—of the Constitution

Zareer Masani

Zareer Masani

Zareer Masani

Zareer Masani

|

16 Jul, 2021

|

16 Jul, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Nehru1.jpg)

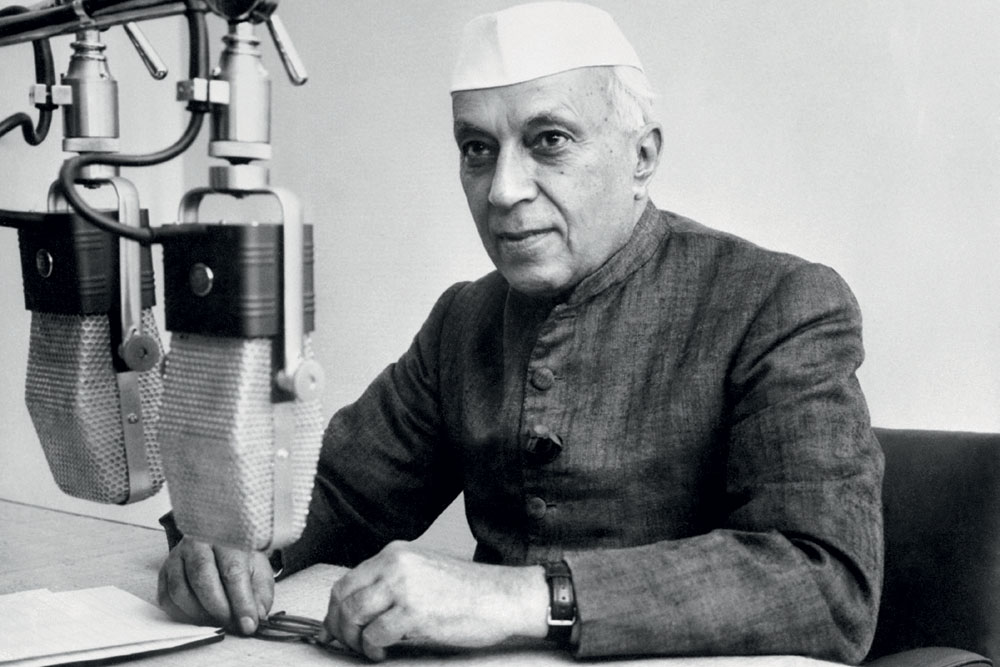

Jawaharlal Nehru moves the resolution for an independent republic in the Constituent Assembly, New Delhi, February 8, 1947 (Photo: Getty Images)

IS THE USUALLY dry history of written constitutions really a surprisingly suspenseful tale of unexpected encounters? We are all familiar with Magna Carta in 1215, but we forget that it was motivated, not by any democratic urge, but by King John’s need for taxes from his barons. It was an early expression of the rule of law, whereby peers of the realm imposed legal curbs on a sovereign executive, in return for taxes and military service.

We have often assumed that this process of what we call constitutionalism is derived from a Western commitment to democracy, exemplified by Magna Carta, then followed after an interval of five centuries by the English Civil War of 1649, and then by the Glorious Revolution of 1689. This is often called the Whig theory of history, with the world progressing to democracy, led by Britain. That’s pretty much the constitutional history we learned at school and university, with the 19th century British historian Walter Bagehot looming large. Bagehot laid down the principles of representative and responsible government, the former referring to legislation by elected bodies, the other to governments being responsible to those legislatures.

More recent scholarship suggests that constitutionalism, long assumed to be the product of Western democracy, was more closely related to the growth of modern, largescale, especially naval, warfare, the high costs that entailed and the consequent need for aspiring military powers to seek constitutional legitimacy with the citizens they were taxing. It also explains why it took so long to concede the vote to women, because they were not deemed necessary for military service.

Rules of government are as ancient as the famous code of the Assyrian emperor, Hammurabi, in 1750 BCE. But it was only from the 18th century onwards that written constitutions began to be seen as a trademark of modern, progressive nationhood. The late 18th century was the period of what’s called the European Enlightenment, when philosophers like Rousseau, Voltaire, Diderot, Locke and Hume all advocated the rule of reason, with laws, institutions and governments chosen by the enlightened. An early outcome was the American constitution, with its emphasis on fundamental human rights, derived from British liberals like Tom Paine. It was the modern world’s first written constitution, unlike the informal British version it replaced, and it set the fashion for written constitutions the world over.

Far less successful were the series of constitutions that followed the French Revolution in 1789, inspired in part by the American constitution and partly by the unwritten British model. Led, not by the masses, but by liberal aristocrats, the French Revolution initially devised a constitutional monarchy, modelled partly on Britain’s and partly on the American presidency. It had a National Assembly, elected by universal manhood suffrage, with an executive appointed by the monarch, then the indecisive but good-natured Louis XVI, who retained a right of veto on legislation.

We are used to thinking of 1950 as the year when independent India enacted its Constitution, but its roots, for better and worse, go much further back. Arguably, the process began in the 1870s with local self-government, based on municipalities and city fathers elected by middle-class Indians and running key cities like Bombay and Calcutta

But this infant French constitution, enacted in 1791, ground to a halt only two years later by 1793, when the king used his veto to defend the Catholic Church. His ministers failed to command a majority in the Assembly, and the Paris mob rioted, invaded the Tuileries Palace and brought down the monarchy. A highly misogynistic and chauvinistic French gutter press pinned the blame on the more decisive, Austrian-born Queen Marie Antoinette, first labelled Madame Deficit, for her reputed extravagance, and later, equally unfairly, Madame Veto. She bravely paid the price, stoically bearing harsh imprisonment, the loss of her husband and children and finally her life.

There followed a series of republican constitutions, much reducing the powers of the Assembly in favour of the so-called Committee of Public Safety and its Reign of Terror. Then came Napoleon’s empire, and finally the wheel turned full circle in 1815 with the Bourbon Monarchy restored under Louis XVIII.

Fifteen years later in 1830, that was replaced by the more limited Orleanist monarchy of his cousin, then came the second empire of Napoleon’s nephew in 1852, and finally the chronically unstable Third, Fourth and Fifth Republics of modern France.

Not surprisingly, Macaulay took a very dim view of such extravagant French constitutionalism, complaining that the French couldn’t resist overthrowing more democratic regimes for more repressive ones. What this French saga certainly demonstrates is how constitutions could be used just as often to shore up monarchies and empires as to safeguard popular republics.

One example we rarely hear of was the constitution that Russia almost got way back in the 1780s. It was the great Nakaz of Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia. Catherine began life as a minor German princess, was married off to a sadistic, half-mad Tsar, Peter III, and was resourceful enough to lead a military coup against her brutal husband. She crowned herself empress in her own right and led Russia for three decades, making it a great power with huge, new territorial conquests.

Alongside her military achievements, Catherine was also a very widely read intellectual who corresponded with French Enlightenment philosophers and led a major programme of Russian modernisation along rational, European lines. The Nakaz was her personally handwritten code of several volumes of regulations for her officials. She rose at dawn every morning to work on it for several hours each day, contrary to the misogynistic, tabloid myth of her as a sexually insatiable, pleasure-loving monarch. In a move unprecedented in Russian history, Catherine submitted her Nakaz to be debated and voted upon in a referendum by Russia’s provincial gentry, including women for the first time in world history. But Catherine’s plans to democratise Russia were rudely interrupted by the French Revolution. The execution of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette was a warning of what could happen to constitutional monarchs in emerging democracies, and Catherine decided to abandon her constitutional experiments.

The Russian Nakaz was the first of many ill-fated constitutional experiments across Latin America, Asia and Africa through most of the 19th century. These could begin like the newly liberated Black slaves on the island of Haiti, which became a republic like its former French revolutionary rulers, and then a few years later set up its own Black monarchy, which rapidly descended into civil war and anarchy. But the Haitian revolution, despite its failings, encouraged the South American colonies of Spain and Portugal to secede from their mother-countries and set up republics, which started off with democratic constitutions that all too often degenerated into military dictatorships. Their constitutions were modelled partly on their northern neighbour, the US, and partly on the so-called Cádiz Constitution, which Spanish liberals had briefly imposed on their own Bourbon dynasty in Spain.

A well-kept secret in our constitutional history is how Jawaharlal Nehru neutralised the American-style chapter on human rights. Hardly had the ink dried on our constitution when, in 1951, Nehru moved the long forgotten First Amendment, undercutting the fundamental rights and the powers of the judiciary

One exception was Brazil, which seceded from Portugal, with its own monarchical constitution and an emperor imported from the Portuguese royal house of Braganza. Other examples of monarchies adopting constitutions as protection from Western intervention were Tunisia and Ethiopia in Africa, Hawaii in the Pacific and, of course, the highly successful Meiji Restoration in late 19th century Japan.

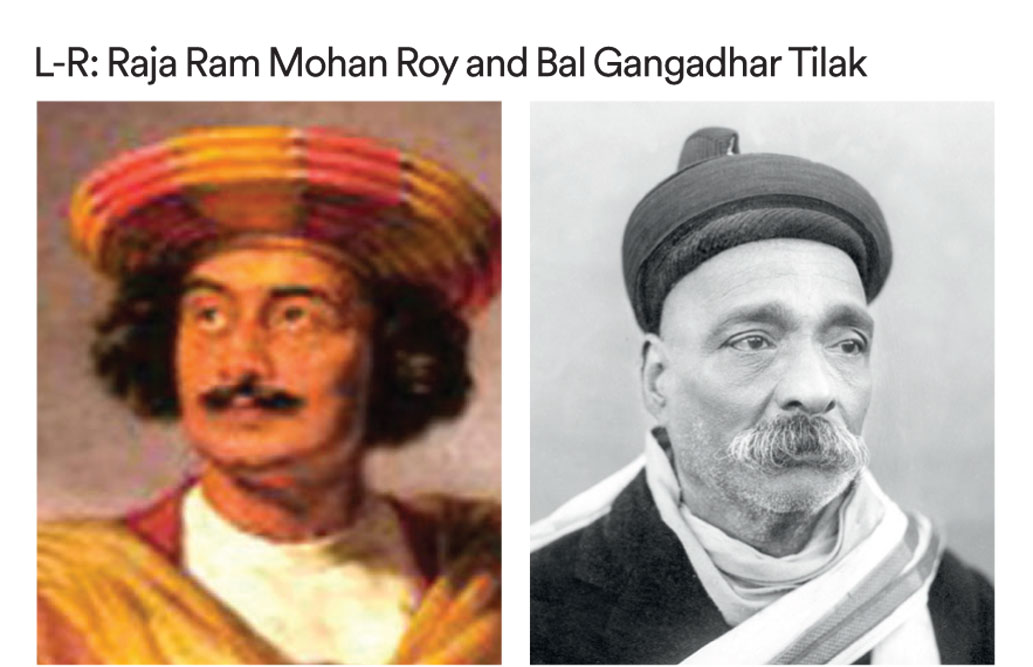

HOW MUCH DID any of this affect constitutional developments in India? Quite a lot more than one might imagine. As far back as the 1820s, the Calcutta Journal published by Raja Ram Mohan Roy was reporting and debating constitutional developments in South America, with its growing enfranchisement of native populations. Roy was an ardent supporter of British education and culture, but also an advocate of reforms to enforce the rule of law on the East India Company by limiting its powers. Although the Company evaded Roy’s more radical demands, the reforming Governor General Lord Bentinck worked closely with him to outlaw sati and female infanticide and to allow the remarriage of Hindu widows.

Another early example of British-inspired constitutionalism in colonial India dates to 1895, when Bal Gangadhar Tilak launched a Swaraj Bill, aiming at Home Rule within the British Empire. His bill aimed to democratise India, much as Irish Home Rulers were demanding for themselves, while retaining the Queen Empress as a constitutional monarch. The history of both India and Ireland might have been very different had such efforts succeeded in making them self-governing Dominions early on.

It’s an interesting paradox that the world’s earliest unwritten constitution, namely Britain’s, has inspired so many offshoots in other parts of the Commonwealth, most countries of which, in contrast with other former colonies, have retained parliamentary democracy in some form. There have been several reasons for this. One has been the flexibility of the British model, making elected legislatures sovereign, with the executive having to retain the confidence of the legislature. The second is the independence, at least theoretical, of the judiciary in enforcing the law on the executive itself. A third factor has been the gradualism with which British parliamentary democracy has evolved, over seven centuries for Britain itself, with the franchise gradually expanding to universal suffrage, while the power of elected legislatures to control the executive also grew over those centuries.

We are used to thinking of 1950 as the year when independent India enacted its Constitution, but its roots, for better and worse, go much further back. Arguably, the process began way back in the 1870s with local self-government, based on municipalities and city fathers elected by middle-class Indians and running key cities like Bombay and Calcutta. Many who later went on to become nationalist leaders cut their teeth in these municipalities, people like Subhas Chandra Bose and Pherozeshah Mehta. My own father began as a Bombay municipal corporator while in and out of jail for Congress civil disobedience. He was elected mayor of Bombay in 1943 and then in 1945 became a front-bench Congress MLA in the then Imperial Legislative Assembly in Delhi, later our Constituent Assembly. Father was elected to every Indian Parliament for the next two decades till 1971, but he maintained that this imperial legislature was the most democratic one in which he ever served.

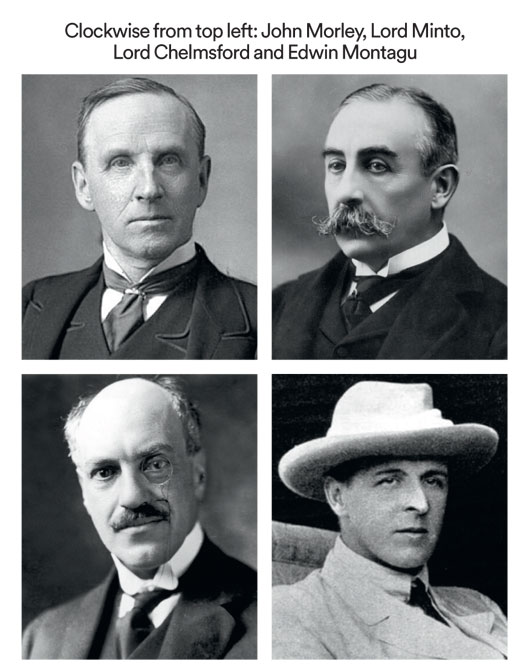

The process of municipal democracy reached the provincial and national spheres in 1909 with the Morley-Minto Reforms, devised by a Liberal secretary of state in Britain and a reformist viceroy in India to introduce advisory legislative councils with Indian nominees at both provincial and an all-India level. However cautiously, the seed had been sown. Although the councils’ powers were advisory, they did allow articulate Congress moderates like Gopal Krishna Gokhale to function as an outspoken if loyal opposition to governors and viceroys.

Ten years later, the important role of the Indian army in World War I prompted another major dose of constitutional liberalisation, the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms, named after another Liberal secretary of state and viceroy. For the first time, India was given the goal of self-governing Dominion Status, or virtual independence on the lines of the White dominions. Central and provincial legislatures were established, all with a majority of Indian legislators elected for the first time, though on a franchise limited to the educated and propertied classes, very similar to the franchise in mid-19th century Britain itself.

The Montford Constitution, as it came to be popularly known, was initially welcomed by most of Congress, including Mahatma Gandhi, but this initial welcome was soon overshadowed by the political fallout of the 1919 Amritsar massacre. The massacre transformed the mood in Congress and eased Gandhi’s path to capturing the organisation for his campaign of non-cooperation.

As far back as the 1820s, the Calcutta Journal published by Raja Ram Mohan Roy was debating constitutional developments in South America. Another early example of British-inspired constitutionalism dates to 1895, when Bal Gangadhar Tilak launched a Swaraj Bill, aiming at home rule

Although the reforms could not have come at a worse time politically, they nevertheless did achieve some practical results. A substantial number of Congress moderates, led by people like Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru and Srinivasa Sastri, seceded from Congress to form the Indian Liberal Party, which contested elections to the new legislatures and accepted ministerial posts in a provincial system known as dyarchy. Under this dual system, elected Indian ministers were appointed to certain “transferred” portfolios like health and education, while sensitive subjects like home affairs and policing were “reserved” for safe British hands.

India was nonetheless given its own seat at the League of Nations and control of its own national budget. In 1922, following the collapse of Gandhian satyagraha, the Liberals were joined, and often replaced in the legislatures, by the Swaraj Party, set up by Congressmen like Motilal Nehru and Chittaranjan Das, who wanted to use the infant legislatures as platforms for further reforms.

Although dominion status was implicit in these reforms, one major hurdle remained. How could Britain transfer power to elected Indian governments and legislatures while also protecting minorities like Muslims, Dalits and Sikhs from Hindu domination? The primary constitutional concern was to avoid the sort of Hindu majoritarian domination we see today, thanks to the first-past-the-post system, in which Muslims number 15-18 per cent of our population, but only 2 per cent of our Parliament.

In 1930-33, the British government hosted a series of Round Table Conferences in London, designed to wean Congress away from civil disobedience and towards a negotiated settlement with the Muslims, Dalits, Liberals and of course the 540 semi-independent princes. Gandhi had insisted on being the sole Congress representative at the conferences, but he found himself outmanoeuvred by people like Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the Dalit leader BR Ambedkar, both of whom insisted on separate electorates for their voters under a first-past-the-post system. Communal electorates had been demanded by Muslim leaders from the turn of the century, conceded by Congress in its Lucknow Pact with the Muslim League in 1916, and incorporated into the new electorates of the Montford Reforms.

The so-called Communal Award of British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald in 1932 also conceded Ambedkar’s demand for separate electorates for Dalits. But then Gandhi resorted to one of his threatened fasts unto death, whereupon Ambedkar, fearing massive retaliatory violence if Gandhi died, gave up his demand for separate electorates for Dalits. Instead, he got the deal under which Dalits have had reserved quotas.

IN 1935, THE latest round of constitutional concessions were embodied in a new Government of India Act, which introduced provincial autonomy and provided for a federal Centre, forming the basis of our very own independence Constitution of 1950, the post-colonial world’s longest surviving constitution.

We forget that Magna Carta in 1215 was motivated, not by any democratic urge, but by King John’s need for taxes from his barons. It was an early expression of the rule of law, whereby peers of the realm imposed legal curbs on a sovereign executive, in return for taxes and military service

The 1935 Act expanded the Indian electorate to 30 million men and women, who either had to pay taxes or hold a matriculation certificate. This may seem small for India, but was still substantial by global standards, and the enfranchisement of women was well ahead of its time. The provincial assemblies were to be wholly elected, ministers were to be responsible to those legislatures, and there were to be no reserved subjects, except defence, finance and foreign affairs, reserved for the Viceroy’s Executive Council at the Centre, still appointed by him, but with more Indian members. The Imperial Legislative Assembly, housed in the wonderful new Lutyens building in New Delhi, now had a majority of elected Indian members and additional legislative powers.

Unlike the Montford Reforms, Congress agreed to work the 1935 Act, contested the elections and won majorities in seven provinces where it formed ministries. Contrary to expectations, the new Congress ministers got on very well with their British governors and ICS officers, and the ministries functioned smoothly for the next two years. The one blot on the landscape was the Congress refusal to form a coalition with the Muslim League in the United Provinces, where the two parties had contested on a united platform. Contrary to expectations, Congress won a thumping majority on its own, no longer needed the Muslim League and unceremoniously dumped them, to the lasting bitterness of Jinnah, who never trusted Congress or Jawaharlal Nehru thereafter.

The 1935 Act had set up a Chamber of Princes, and its all-India provisions envisaged a federal Central government, including Congress, the Muslim League and the princes. It’s just possible this might have emerged, had it not been for the outbreak of World War II and the resignation of Congress ministries in protest at not being consulted about India’s entry. Whether one considers this an act of pique or principle, it did more than anything else to open the way for Partition. Congress withdrawal from constitutional politics, followed by the Quit India movement, proved to be something of an own goal in handing power to the Muslim League. The League now adopted its famous Pakistan Resolution in 1940 and cooperated fully with the Raj, rapidly expanding its power base across Muslim India.

With the Congress return to constitutional politics in 1945 and fresh elections, the Imperial Legislative Assembly at the Centre became the main arena for political activity, and two years later, in 1947, it became the Constituent Assembly of independent India. This came after the failure of the Cabinet Mission Plan, a last- ditch attempt by the British government to hold the subcontinent together with an ingenious constitutional experiment. It envisaged a loose federal Centre for defence and foreign affairs, with strong provinces, which could form groupings of their own and which had the right to secede after 10 years. The hope was that this cooling-off period might enable politics to coalesce around non-sectarian lines, with time healing those sectarian divisions.

The American Constitution, with its emphasis on fundamental human rights, was the modern world’s first written constitution, unlike the informal British version it replaced, and it set the fashion for written constitutions the world over

Given the holocaust of Partition, even a temporary constitutional sticking plaster like the Cabinet Mission Plan might have been worth trying, but Nehru, by then interim prime minister, would have none of it. As a committed socialist, he was set on having a strong Central government that would implement his economic policies, instead of having to share power with Jinnah and his commitment to free markets.

A hugely important but well-kept secret in our constitutional history is how Nehru later succeeded in neutralising the Constitution’s American-style chapter on human rights, which Ambedkar and my own father had done so much to draft. Hardly had the ink dried on our Constitution when, in the summer of 1951, Nehru moved the long forgotten First Amendment, undercutting the Fundamental Rights guaranteed in the Constitution and the powers of the judiciary to enforce them. Moving the amendment on May 16th, 1951, Nehru declared that Fundamental Rights, such as rights to property and freedom of expression, were ideas of the 19th century, now overtaken by 20th century ideals of social reform enshrined in the Constitution’s Directive Principles of State Policy, which reflected the radical programmes of Congress. The political compulsions behind this rhetoric lay in the stalling of the Government’s social and economic policies by a wide-ranging coalition of litigants, including zamindars, businessmen, newspaper editors and communist campaigners, all of whom had successfully challenged Central and state legislation in the courts, thereby limiting government attempts to curb civil liberties, regulate the press and confiscate zamindari lands without proper compensation.

THAT NEHRU SHOULD have chosen to prioritise such socialist reforms so dear to his heart is no surprise. He had, after all, rejected power-sharing with Jinnah’s Muslim League, partly because it represented what he considered conservative elements. Nehru had preferred Partition, so that Congress led by him could be master in its own house, free to implement its socialist policies. Despite Nehru’s frequent reference to Westminster-style parliamentary norms, he had little patience with multi-party democracy, and his model of centralised state planning owed more to the Soviet example of one-party rule. The First Amendment was instrumental in constructing such a one-party state by neutralising at one stroke all the political opponents of left and right who might have clubbed together an effective parliamentary opposition.

What is surprising is how Nehru overcame reservations among some of his own close colleagues and parliamentary backbenchers and faced down opposition from some fearless critics. Foremost among them was Sardar Patel, who died just a few months before the Amendment, but whose reservations had been overcome by his own desire to suppress communist insurgency through preventive detention without judicial intervention. Similar concerns may have persuaded his successor as home minister, C Rajagopalachari, into supporting Nehru, surprisingly so given his later championship of liberal opposition by the Swatantra Party. And then there was Nehru’s law minister, BR Ambedkar, chief architect of the Constitution and once the champion of its Fundamental Rights, which he had formerly described as “the very heart and soul of the Constitution”. His support for Nehru’s Amendment was secured by the promise of reservations in public services for Dalits, otherwise likely to have been found ultra vires of fundamental rights to employment.

Finally, there was the president of the republic, Rajendra Prasad, himself a small zamindar and staunchly opposed to measures to sweep away zamindari without proper compensation. The president made several attempts to advise and warn his ministers against this assault on Fundamental Rights, although he stopped short of a public challenge after Nehru threatened to resign and force a constitutional crisis.

The process of municipal democracy reached the provincial and national spheres in 1909 with the Morley-Minto reforms. Ten years later, the important role of the Indian Army in world war I prompted another major dose of constitutional liberalisation, the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms

It’s little realised today that the First Amendment, virtually a second constitution, created a special schedule where laws could be placed to make them immune to judicial review, according to one jurist “an obscenity created by wilful resolve”, the mother of all subsequent breaches of our Fundamental Rights. The heroic if disparate opposition the Bill provoked ranged from Syama Prasad Mookerjee and his Hindu Mahasabha to remnants of the Muslim League, representatives of the zamindars, socialist politicians like Jayaprakash Narayan and Acharya Kripalani and communist journalists like Romesh Thapar. Some of Congress’ own backbenchers questioned the wisdom of a provisional Parliament, elected on a limited franchise in 1945 as the Imperial Legislative Assembly, enacting such a momentous measure. But when the final vote came, most Congress MPs fell in line or abstained.

Ironically, a horrendous thunderstorm broke over New Delhi as Parliament debated the Bill, with MPs drenched in rain through open skylights and the chamber plunged into darkness because of an electrical failure. This battle, fought almost 70 years ago, has cast a long shadow on our post-Independence politics, providing the constitutional basis for elective, one-party dictatorships under Nehru, his daughter Indira and the Bharatiya Janata Party today. As my fellow-historian Tripurdaman Singh has so cogently argued, what was lost in this assertion of unlimited parliamentary sovereignty was the independence of the judiciary and the rights of the individual against the state. It has meant that the executive arm of the state, provided it has the necessary parliamentary numbers, can expropriate private property,

nationalise private companies, ban newspapers, arrest dissidents without trial and impose caste-based quotas on employment, and all this in the name of democracy.

It may seem ironical today how eager most Congress leaders were to resume the autocratic reserve powers of the colonial rulers they had just evicted. The result may have been the death-knell of the old landed aristocracy via land reforms, but it has also seen the rise of corrupt, new elites based on a competitive scramble for job reservations for proliferating “backward” castes. The results of Nehru’s emasculation of the Constitution and the judiciary’s helplessness to enforce it are amply demonstrated today in the Supreme Court turning a blind eye to the subversion of fundamental freedoms in Kashmir.

Ultimately, constitutions are only as powerful as the political will to implement them. The prime example of a paper constitution never implemented was the one Stalin commandeered in 1936 for his Soviet dictatorship. But perhaps even such paper exercises are a useful text to which democratic reformers can and do turn. One optimistic example is how human rights campaigners against the (Vladimir) Putin dictatorship still hold up copies of the Russian constitution with the rights it promises. Is it time for liberal Indians to do the same, preferably with our own unadulterated, original Constitution, minus Nehru’s destructive First Amendment?

(This essay is based on a lecture to the Museum Society of Mumbai delivered on June 24th, 2021)

/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Cover_Kumbh.jpg)

More Columns

The lament of a blue-suited social media platform Chindu Sreedharan

Pixxel launches India’s first private commercial satellite constellation V Shoba

What does the launch of a new political party with radical background mean for Punjab? Rahul Pandita