Stupidity and Credibility In the Time of a Pandemic

A dark comedy of errors

Dipankar Gupta

Dipankar Gupta

Dipankar Gupta

|

23 Apr, 2021

Dipankar Gupta

|

23 Apr, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Darkcomedy.jpg)

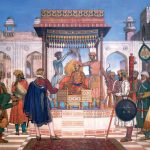

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

COVID AND THE KUMBH MELA provide near-laboratory conditions to figure out why social policies go wrong. In this, we cannot but recall Amos Tversky, Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman’s colleague, who said that most of the time we don’t study artificial intelligence but natural stupidity. Social scientists, planners and political leaders are loath to accept this, but it is true; we are either studying stupidity or manipulating it. Economics, Political Science, Sociology, each studies its own brand of stupidity and disciplines are built on that foundation.

However, in general we can distil the various stupidities that exist around us into two main categories. The first is to believe that people are comprehensively ignorant and only scientific advice can save them. Smart as this may seem, at first sight, it is actually stupid, for it does not take into account the context of social interventions. The second goes in the reverse direction but it is again stupid. It holds that people’s choices are inviolable, even sacred, and it would be incorrect, if not immoral, to disregard them. Both these errors arise from ‘fast thinking’.

Our recent experiences with the Covid pandemic give enough ground to demonstrate our contention.

Are people comprehensively stupid to resist science? A slum dweller may not be stupid in disregarding social distancing norms but ignores them because they are impractical and very difficult to observe. Likewise, poor workers may resist inoculation for fear they would lose wages, first on account of the effort needed to get the shot and then to recover from its after-effects. The science is good, but the context makes them suspect. As we see, following science has major, measurable inconveniences for unclear benefits. So are poor workers stupid? Not really.

The second error is when policymakers, leaders and intellectuals swing to the other extreme and consider people’s choice as ultimate, not to be trifled with. Milton Friedman famously advocated this approach with the clever caveat that choice exercised should not hurt others. However, no clarity here about the hurt to those whose choices have been denied. For example, disallowing Kumbh Mela’s shahi snaan may constitute hurt to devotees, but it can also spread the disease. So, which hurt is greater, as hurt cuts both ways?

It’s time now to bring in another critical variable besides stupidity, and that is ‘credibility’. Credibility, or lack of it, further thickens the plot and that often creates a comedy of errors when advocating social policy. Apart from lifetime experiences that are a strong conditioning factor, accepting information depends more on the credibility of the source than on the content or the knowledge given out. If I win your trust, say on language rights, I might also get you to campaign for the environment, even though you may have never earlier thought of it.

Sources that have won credibility, either because of their economic sagacity, cultural purity or military heroism or incorruptibility, influence people more than scientists ever can. This is because science takes long but once your mind has decided, after deliberation, to trust a source of information, it is much easier to go with it. After credibility is secured, the same source can dispense other information and the chances are that they will be accepted without further scrutiny. The credibility test, once won, has a long shelf life.

Sadly, political leaders who are considered credible sources of information and wisdom spoil it all by not fully trusting their powers. Consequently, they go on trying to win people over when they no longer need to, resulting in what may be called ‘campaigning redundancy’. On account of this, popular views get a further boost from leaders who could have just as easily used their ‘source credibility’ status to scorch them. By giving in to ‘campaign redundancy’, high source-credible leaders needlessly cede much of the advantages they toiled so hard to acquire.

Sadly, political leaders who are considered credible sources of information and wisdom spoil it all by not fully trusting their powers. Consequently, they go on trying to win people over when they no longer need to. On account of this, popular views get a further boost from leaders who could have just as easily used their ‘source credibility’ status to scorch them

While no amount of source credibility could have made leaders enforce social distancing in slums, matters may have been different in the case of the Kumbh Mela or in election shoutouts. However, because of campaign redundancy, leaders did not want to offend what they believed was the popular mood and went ahead with both these events. As a result, given the source credibility of leaders, masses found no reason to stay away from Haridwar or from the election battle grounds, both of which attracted lakhs of people.

This was a near-perfect staging of a comedy of errors. Leaders did not want to risk dialling down pilgrimages and election rallies for fear of switching off people. So they played to what they thought was the gallery, little realising the redundancy of it all. As they already had credibility in the bag, the masses would comply if election canvassing were made virtual or the Kumbh Mela largely ‘symbolic’. Therefore, the masses need not have been pampered and pampering ended up actually hurting the masses.

Our brain has a way of discouraging difficult decisions and promoting easy ones. This is why Amos Tversky said that most of the time he studied natural stupidity. In one case, our brain chooses the stupid route of trusting past practice and being more comfortable with what is tried, tested and familiar. In another case, we depend on others to provide us with thought leadership, especially those who have proven their credibility, even if that were only on one significant, momentous occasion. This is also a stupid move, but it happens all the time.

This kind of mass suspension of difficult decision-making is usually the preserve of the young because they come to conclusions swiftly and mistake conviction for correctness. The older one gets the slower is one’s response and thus greater the possibilities of coming to decisions which need deliberations. In such instances, a leader’s source credibility will not carry as much weight as it would with the young who are quick to react. In all likelihood, this has to do with the consciousness of age where physical infirmity also tells the mind to go slow and think more.

Those who believe in scientific advice are also willing to change their opinion if science changes its mind and if its recommendations are properly contextualised. This is difficult, for a majority of people want certainty all the time. That is why when they see a source-credible leader without a mask and disinterested in social distancing, they feel the old, comfortable world is still around and they need not panic. Established behavioural practices continue because source-credible leaders are afraid to test their strength and that helps the coronavirus to happily multiply.

ARE THERE WAYS we can overcome this tendency towards choosing the easiest of all options? Remember, some of democracy’s major advances happened because leaders did not just kick the tyres to see if the vehicle was travel worthy. Instead, they took a hard look at the machine, tuned it up, even changed some of its parts. This is how democracy grew to include women, minorities and propertyless people. One could add to this list the banning of child labour. Today, many take these features for granted, forgetting that they did not come easy.

Given the crisis-laden situation in India today, it is time leaders realised how wasteful ‘campaign redundancy’ is and prepared themselves to smash the mirror. We have dithered for years on major social reforms, making room instead for what we thought were ‘popular beliefs’. That led to wasting resources on needless subsidies, both to the rich and the poor

Most important of all, these great changes happened because leaders with source credibility did not waste their advantage in ‘campaign redundancy’, but used it to alter people’s ways. None of the significant milestones of democracy, mentioned earlier, came about because that is what people wanted. In fact, the majority often did not, but source-credible leaders persisted and that is why democracy is what it is today. What Bertolt Brecht said about art is equally valid for democracy. For Brecht, art should not mirror the world but, like a hammer, smash it.

Source-credible leaders too, should not waste their advantage in mirroring the world and indulging in campaign redundancy. They should, like good artists, instead break the mirror for the greater good. There is no ideal moment either to break the mirror for ducks will never, on their own, stand in a row. When child labour was abolished in Britain, poor coal miners did not like it. It took at least 15 years for the benefits of school education to show up, but leaders persisted and weathered that storm and today they are admired for holding up their end.

This process of abolishing child labour began in Britain in 1833, but it took the 1878 Factory Act and the 1880 Education Act to finally eradicate it. It was a long struggle and much of this was achieved, not by people pressure, but because leaders with source credibility fired. Without mass support, these heroes pulled with their teeth till they finally succeeded. This is true for practically every major democratic achievement, including India’s fight against untouchability, where Gandhi stood firm and took on majority prejudices.

Given the crisis-laden situation in India today, it is time leaders realised how wasteful ‘campaign redundancy’ is and prepared themselves, instead, to smash the mirror. We have dithered for years on major social reforms, making room instead for what we thought were ‘popular beliefs’. That led to wasting resources on needless subsidies, both to the rich and the poor. We spend more in real terms than the US does in subsidising the farming sector in India, but it is still so poor. The comedy of errors plays out in so many diverse settings.

Instituting measures that would rid our economy of informal labour, setting up universal health and insurance schemes, making quality education available to all, require leadership. This is not the work of a maverick who gambles or opts for the first rattle out of the box. None of these happened easily elsewhere for they required leaders to take gutsy risks in order to secure long-term gains. The mirror only reflects the status quo, no matter how tarty the subject makes itself out to be. ‘Campaign redundancy’ bolsters this tendency and it is time we acknowledged that.

Once the mirror is smashed, a new world opens up, especially for leaders who already have a bagful of credibility at hand. They can now leverage their advantage to accomplish tasks whose significance does not strike masses who want instant gratification. We have had many leaders blessed with source credibility, yet very few junked campaign redundancy to help people out of their stupidity and set up a true welfare state. If they had, workers would not be scurrying to their villages today fearing another de facto, if not de jure, lockdown.

What is clearly not stupid is democracy because democracy’s fundamental precept is fraternity. Unfortunately, like everything not stupid, it takes time, diligence and contemplation to realise its worth. Fast thinking, which encourages campaign redundancy, must be given a rest. When we link our individual fates to those of

others, all of us are better served

The first wave of the current pandemic was clearly not enough to break the thrall of campaign redundancy. Murphy’s law is still in full operation here for all that can go wrong has gone wrong. Yes, it will require time and effort to rid informal labour and set up universal healthcare and education. But leaders with source credibility can, at least, take the lead in terms of Covid-appropriate behaviour and keep people from doing what comes naturally to them, that is, being stupid. For this, our elected representatives need to call campaign redundancy’s bluff.

Milton Friedman’s votaries are wrong because individual choices do not add up to social good. The powers of the ‘unseen hand’ are vastly exaggerated much like the way we hope ‘herd immunity’ will finally deliver us from the pandemic. What we now know is that if herd immunity were to happen on its own, without the ‘seen hand’ of inoculation, millions would die before that kind of cover is achieved. Is all that suffering really worth it? Even those who live through it will have lost loved ones and such losses are irreparable.

Individuals on their own exhibit stupidity at nearly every turn and rarely rise above that level. The belief that individuals are rational and rationalities add up to make society rational is a dangerous proposition that Friedman encouraged. The wisest thing humans can do is to encourage solidarity for we live together in this limited planet and nature always does what it has to do. Which is why nature is neither good nor bad, wise or stupid, and that is true for viruses as well. It is for us to be wise for, unlike nature, we have also the choice to be stupid.

What is clearly not stupid is democracy because democracy’s fundamental precept is fraternity. Unfortunately, like everything not stupid, it takes time, diligence and contemplation to realise its worth. Fast thinking, which encourages campaign redundancy, must be given a rest. When we link our individual fates to those of others, all of us are better served. Just think: private hospitals and schools would be of a higher standard, if they survived at all, once universal health and education were offered at quality levels.

This is the time, if there ever was one, for leaders to recognise the severe negative fallout of campaign redundancy and gear up, in full consciousness, to maximise their social credibility. If people have to be helped out of their stupidity, leaders must take the lead and realise their role as fraternity’s pom-pom bearers. Source credibility takes long to acquire which is why it is a real pity if it is squandered in campaign redundancy and in yielding to popular impulses that move from issue to issue with great rapidity and with little thought.

Sadly, it is not just leaders who often squander their source credibility. In these Covid times we find that doctors too are undermining their institutional and personal source credibility. So many of them are needlessly, dangerously too, prescribing remdesivir to fight Covid-19 just because their patients pressure them to do so.

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai

Love and Longing Nandini Nair

An assault in Parliament Rajeev Deshpande