SCOTTISH AUTHOR Douglas Stuart’s debut novel Shuggie Bain, a coming-of-age story about a young, queer boy and his alcoholic mother, won the Booker Prize last week. The book is set in Glasgow in 1981, and so our titular hero grows up during Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s tenure. Throughout the narrative, we see how Thatcher’s economic policies have affected the lives of working-class people in the region. Early in the novel, the protagonist’s parents have to move out of their city flat and into a rundown neighbourhood called Sighthill. And because the protagonist’s father, Hugh ‘Big Shug’ Bain, is a taxi driver, we see evidence of a town’s economic collapse through his eyes: droves of people out of work, buildings falling into disrepair, rampant drug abuse and alcoholism.

Thatcher’s time as Prime Minister (1979-1990)—especially during the Falklands War—has inspired many writers and artists. Notable examples include Pink Floyd’s 1983 album The Final Cut, Jorge Luis Borges’ poem ‘Juan Lopez and John Ward’, the Denzel Washington film For Queen and Country and David Mitchell’s coming-of-age novel Black Swan Green. Recently, Gillian Anderson played Thatcher in the fourth season of Peter Morgan’s Netflix series The Crown. Thirty years after she was voted out of office, Thatcher continues to evoke impassioned, visceral responses from fans, detractors—and creators such as Morgan and Stuart. Her devotees, mostly older, wealthier commentators, see her as the strongwilled leader who rescued the British economy from its post-war stagnation. Her detractors point towards the high social cost of this enterprise: unemployment doubled in her first three years in office, while other social benefits were slashed, too. Thatcher, quite simply, was responsible for infusing ruthlessness and a cult of personality into British politics and society.

Stuart, on the evidence of Shuggie Bain, a firm believer in ‘show, don’t tell’, never critiques Thatcherite economics explicitly. Instead, we see out-of-work miners hanging around their old workplace. The overgrown ‘weedy grass’, the decrepit iron gate and, of course, the profanity against the Tories. Stuart says what he has to say with minimum fuss and no expository dialogue. ‘At the back of the car park sat a high brick wall with an old iron gate set into it, held tight with a heavy padlock and chain. The guard’s booth at the side was tilting at a funny angle, and a thick layer of weedy grass grew on its roof. The mine was shut. Someone had painted ‘Fuck the Tories’ on the plywood barrier. It looked like it was closed for good… They all wore the same black donkey jackets and were holding large amber pints and sucking on stubby doubts. The miners had scrubbed faces and pink hands that looked free of work. It seemed wrong, these men being the only clean thing for miles.’

One of the few outright jokes at the former Prime Minister’s expense happens when an unemployed man’s mother tells ‘Big Shug’ about being asked to ‘try South Africa’ if her son’s looking for work. The angry woman lets loose a volley of abuse directed at the government. She says: ‘Go all the way to South Africa so they can build cheap boats there and send them home to put more of our boys out of work? The shower of swine.’

The South Africa bit is a reference to one of the scandals Thatcher had to contend with while in office. After it became clear that she was not in favour of imposing economic sanctions on apartheid-era South Africa, there were accusations that her stance was influenced by her son Mark’s

business dealings in the country. In 2005, Mark was given a four-year suspended sentence for funding a coup d’état attempt in Equatorial Guinea (while he was living in South Africa).

Thatcher’s misguided and convoluted opinions about gender turn up frequently in pop culture depictions. Her public persona was a curious mixture: the words and the actions themselves were modelled after male authoritarian leaders, whereas the voice, the diction and the mannerisms, even her signature purse, were all part of a self-consciously ‘feminine performance’. Hilary Mantel, the British author and two-time winner of the Booker Prize, had made the same remark about Thatcher in a 2014 interview with The Guardian, published shortly after the release of her short story collection The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher. ‘She imitated masculine qualities to the extent that she had to get herself a good war… The idea that women must imitate men to succeed is anti-feminist. She was not of woman born. She was a psychological transvestite.’

IN THE TITULAR story from Mantel’s collection, a would-be Thatcher assassin from the Irish Republican Army (IRA) enters the unnamed female protagonist’s flat because it offers the best possible shot at the Prime Minister, who’s scheduled to pass by the neighbourhood shortly. Initially fearful, even dismissive of the young man’s motives, the protagonist eventually warms up to the young man with a working-class Liverpool accent. His sardonic jokes about the Prime Minister make her understand just how much Thatcherite economics hurt working-class families.

Indeed, in most works of art that reference Thatcher, the working-class hero’s lament is a formal feature. The societal conflict and resentment that grew out of Thatcher’s preference for ‘cutting-edge’ industries like technology and finance, and her open scorn for millworkers, miners and so on, is also depicted beautifully in Shuggie Bain. Towards the end of a hard day of taxi driving, ‘Big Shug’ thinks about all the things he had heard from disgruntled, often unemployed passengers.

‘Glasgow was losing its purpose, and he could see it all clearly from behind the glass. He could feel it in his takings. He had heard them say that Thatcher didn’t want honest workers anymore; her future was technology and nuclear power and private health. Industrial days were over, and the bones of the Clyde Shipworks and the Springburn Railworks lay about the city like rotted dinosaurs. Whole housing estates of young men who were promised the working trades of their fathers had no future now. Men were losing their very masculinity.’

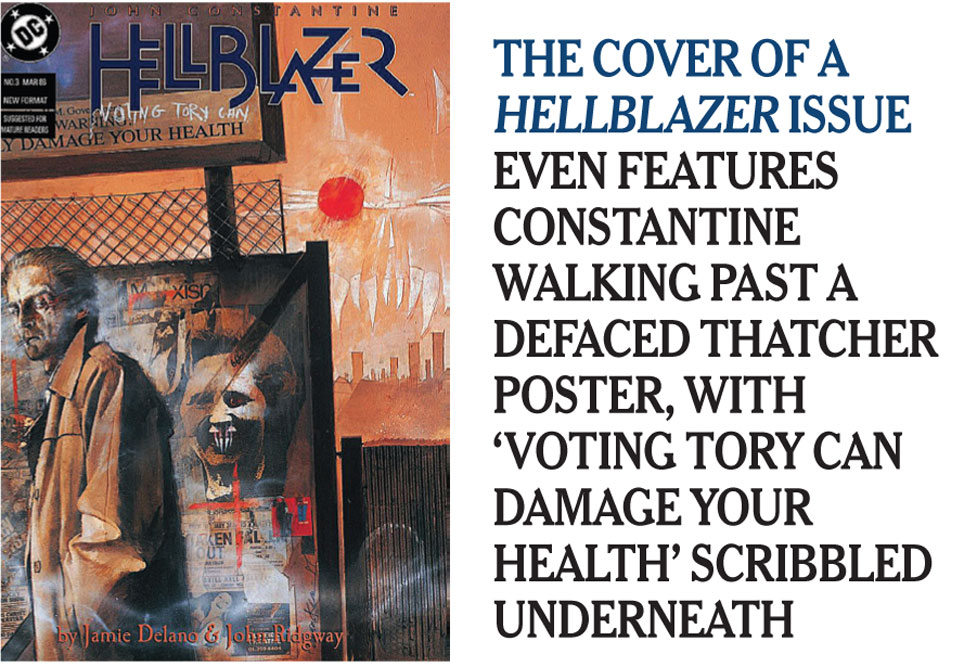

In 1988 (while Thatcher was still in office), British writer Jamie Delano and artist John Ridgway’s run on the DC Comics horror series Hellblazer (featuring John Constantine as protagonist) included several storylines revolving around the plight of the working-class Englishman. A multi-issue story arc, for example, sees Constantine investigating a string of gruesome murders where the victims are all London yuppies working in the financial sector—they are killed via ‘their own excesses’, we are told.

The cover for issue #3 even features Constantine walking past a defaced Thatcher poster, with ‘Voting Tory can damage your health’ scribbled underneath. For good measure, we are also introduced to Blathoxi, a ‘financial demon and lord of flatulence’, who informs Constantine that Thatcher’s tenure has resulted in a giant spike in greed—always great news for the soul-harvesting business. ‘The haves are so terrified of becoming have-nots that it’s a dog eat dog out there. We will corner the UK soul market now,’Blathoxi informs Constantine gleefully.

David Mitchell’s novel Black Swan Green (2006) is narrated by its sweet-natured, stammering 13-year-old protagonist Jason, and therefore its preferred mode of critique could not have been sarcastic one-liners of the sort we see in Hellblazer or The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher.

Instead, the revelations are slow and gradual at first—we see Tom Yew, a boy from Jason’s village, going off to fight the Falklands War, a war that he doesn’t survive. We also see Jason’s father losing his managerial job amidst cost-cutting measures at his workplace—because of these happenings, young Jason’s hitherto respectful attitude towards Thatcher changes.

At the beginning of the book, he imagines meeting Thatcher alongside Ronald Reagan one day but by the end he understands the basics of how the prime minister is indirectly responsible for Tom’s death and Jason’s father getting laid off.

The real-life Thatcher changed her voice and tonality significantly after becoming Prime Minister. The aim was to make her sound less of a shopkeeper’s daughter, and to add gravitas. Because of this, there was a higher-than-usual (this is politics, after all) degree of contrivance in her public speeches—the effort it took to literally change the way she spoke showed in every sentence. Mantel diagnosed Thatcher’s complicated relationship with class succinctly: ‘She couldn’t turn herself into a posh girl with the right vowels. If you’re that dissatisfied with yourself you try to fix other people, and if they won’t be fixed you become punitive.’

BUT THESE MOMENTS are few and far between. For the most part, British artists have made no secret of their hatred of Thatcher. Roger Waters, for example, wrote the song Pigs: Three Different Ones on Pink Floyd’s 1977 album Animals. The second verse is basically Waters’ elaborate way of telling off a certain leader in power. After decades of teasing fans, in a 2019 interview Waters stated for the record that these lines were about Thatcher:

‘Bus stop rat bag

Ha ha charade you are

You fucked up old hag

Ha ha charade you are

You radiate cold shafts of broken glass

You’re nearly a good laugh

Almost worth a quick grin

You like the feel of steel’

The ‘bus stop rat bag’ refers to a statement popularly attributed to Thatcher (though there’s no proof that she said this): “Anybody over the age of 25 who continues to ride the bus is a failure.” It’s the kind of thing that fits very well with Thatcherism’s innately cruel, each-man-for-himself philosophy (in The Crown, we see Thatcher claiming that a sense of collective duty was an antiquated idea and ‘holding England back’). The ‘feel of steel’ refers both to Thatcher’s warmongering and her nickname ‘the Iron Lady’.

The Crown’s fourth season ends with the final months of the Thatcher era. As per usual for the show, a few liberties are taken with history in the name of narrative elegance. In real life, Thatcher offered the queen her letter of resignation in person, with minimal fuss. Here, Anderson-as-Thatcher champs at the bit, refusing to accept the writing on the wall, refusing to aid a peaceful transition of power. “My job is being stolen from me,” she says, once again bypassing irony. She tells the queen that she’s dissolving parliament and that she won’t go down without a fight.

In November 2020, doesn’t that pattern of behaviour sound awfully familiar?

More Columns

Modi Govt accepts Opposition Caste challenge Ullekh NP

Subhanshu Shukla: The Second Indian In Space Open

Centre revamps National Security Advisory Board, appoints Alok Joshi as chairman Open