The Liberal Dilemma

Is there something missing in how White progressives understand race?

Poulomi Chakrabarti

Poulomi Chakrabarti

Poulomi Chakrabarti

Poulomi Chakrabarti

|

30 Oct, 2020

|

30 Oct, 2020

/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Liberaldilemma1.jpg)

An anti-racism protest in New York, June 14 (Photo: Getty Images)

The 2020 election is fought in the midst of the largest social movement in US history. ‘Black Lives Matter’ has shaped the policy platform of both presidential candidates. The Democrats, not surprisingly, are more progressive. Yet, as the former mayor of Minneapolis noted, racial inequality is amongst the worst in cities run by the Democrats. One might argue that we need our politicians to be more radical—America’s broken system needs to be rebuilt from the ground-up. But left-leaning politicians like Bernie Sanders, who proposed just that, have not had much success with Black voters. Yes, his campaign could have done more to articulate the concerns of minorities (his 2020 campaign was an improvement over the last.) But is there something fundamentally missing in how white liberals understand race?

Anti-Black discrimination is deeply ingrained in American society due to its long history of slavery, but this ‘liberal dilemma’ is not unique to the US. America’s more progressive neighbour in the north, where I currently work, is an exemplar of multiculturalism for French-speaking Quebecers while its indigenous population was subject to genocide until recently and continues to be mistreated. The high incidence of poverty in India should have predicted the success of the left. Yet, barring a few exceptions, caste-based parties dominate politics in most states. Indigenous groups in Bolivia were forced to create their own political parties in spite of a strong left. Why do liberals continue to fail marginalised groups? Can social science teach us something about this dilemma?

Societies with long histories of group-based discrimination owing to, say, legacies of caste, slavery, colonialism or apartheid, are not just stratified by class, but also by social status. In such societies, class and status overlap. Black Americans and lower castes, for example, are more likely to be employed in low-skill and low-paying occupations. This is not a coincidence. Historically, this division of labour was institutionalised through slavery and the caste system. But even after formal legislation dismantled these institutions, the beliefs that legitimised these hierarchies continue to endure. While we think of political ideology largely in terms of the left-right spectrum, or support for redistribution, status is often a stronger predictor of political behaviour in hierarchical societies. Status inequality relates to differences in honour or prestige between groups. Status is based on widely shared beliefs about the innate differences in the ability and worth of different categories of people. These beliefs dictate social relations. In the process, they reinforce inequality between groups through three distinct ways.

One, status beliefs or racial stereotypes shape broader societal perceptions of competence of different groups, thus providing an implicit intellectual justification for discrimination. Discrimination against Black Americans in the employment, housing, and especially the criminal justice system, is well-documented. Controversial policing measures like ‘stop-and-frisk’ have been defended on statistical grounds. Scientific racism has long been discarded but a recent study finds that Black Americans are undertreated for pain because white medical professionals hold unfounded beliefs about biological differences between Black and white people. Similarly, few people in India would openly admit to being casteist, but those who believe in the ideology of karma and caste—that being born into a lower caste is a reflection of sins in the previous life, are more tolerant of inequality and oppose affirmative action. Status beliefs also dictate social relations between groups. Members of non-dominant groups face humiliation, despite their class and achievements. Barack Obama, for example, has written about his experiences of racism as a Senator—‘I can recite the usual litany of petty slights that during my 45 years have been directed my way: security guards tailing me as I shop in department stores, white couples who toss me their car keys as I stand outside a restaurant waiting for the valet, police cars pulling me over for no apparent reason.’

Black Lives Matter is encouraging because it is able to gather widespread support across ethnic and class boundaries. Its demands are expansive, targeting both redistribution and recognition

Two, members of marginalised groups often internalise negative status beliefs about their group. This shapes their expectations of self-worth, which in turn influences their behaviour and performance. In experimental settings, women perform worse in maths when reminded of their gender. Black athletes underperform in tasks framed as ‘sports intelligence’. Publicly revealing the caste of lower-caste schoolboys reduces their problem-solving abilities. Identity is not just something that’s in their head. It has real consequences. Research, surprisingly, finds that Black Americans generally endorse unfavourable stereotypes of their group as ‘lazy, irresponsible, and violent’, even more strongly than the whites. The policy response, as a result, is a call for change-from-within. Any exploitative social order—patriarchy, caste, racism, colonialism—cannot survive unless members of the subordinated group buy into the myth of their inferiority.

Finally, the bias generated by status beliefs shapes our social networks—whom we work and collaborate with, whom we date and marry, whom we choose to live around. One may not be racist, but if our networks only include people who look like us, that decades of residential segregation has ensured, we are likely to be exclusionary by design. Over the long term, the cumulative effects of discrimination, notions of self-worth, and narrow social networks add up. The strength of status beliefs contributes to the accumulation of resources and sustains group-based inequality.

Of course, liberals are not blind to racial inequality. They are more likely to worry about inequality than conservatives. But most liberals, and Marxists in particular, believe that racial inequality is merely a disguise for economic inequality. Identity is secondary and epiphenomenal—once economic inequality is eliminated, racial inequality will automatically fade away. If the poor don’t fight for redistribution, it must be ‘false consciousness’. Hence, the famous slogan: ‘Workers of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but your chains!’ When Bernie Sanders spoke about racism, it was often in the context of proposals oriented towards all working-class Americans, which would have also benefitted Black Americans. Too much focus on identity is even seen as harmful because it divides the working class. Sociologists and political activists Richard Cloward and Frances Fox Piven recall that the severest criticism of Black movements in the US came from the leftist scholars who argued that the movements worsened class divisions and failed to win meaningful economic gains.

YES, BETTER quality schools and universal healthcare would address many concerns in Black communities, but status hierarchy is more complicated than pure class. Expansive social policy is not a cure for discrimination. Countries in northern Europe outrank the US in human development but are less tolerant of ethnic diversity.

Historical discrimination, in particular, presents a unique chicken-and-egg problem—if minorities form a significant proportion of the poor, the high social distance and distrust between groups is not conducive to cross-class solidarity that redistributive politics demands. But the way to ensure that minorities do not remain disproportionately poor is greater redistribution. Status inequality was precisely the reason why the Civil Rights Movement had limited success. The deep racial cleavage did not allow for multiracial alliances. Not unlike Trump’s core base in the last election, the white working class in the South was motivated by racial fears and an inclination to preserve its status. The leftist scholars are right in arguing that the movement had limited redistributive gains. But it brought an end to lynching and reduced terror as a means of social control. No small feat. Given the persistence of violence as a means of social control, it should not be a surprise that protestors are demanding the abolition of the police.

In hierarchical societies around the world, groups are not just motivated by concerns of material well-being, but also the fight for status. Isabel Wilkerson’s book on social hierarchy in America rightly refers to race as a type of caste system. Members of dominant groups seek to preserve their status, through, say, segregationist policies or restricting access of other groups to institutions of power. Members of marginalised groups seek equalisation of status, as a means to remedy domination, non-recognition and disrespect. At either ends of the spectrum, concern for status can often trump class interests. Poor white communities and poor Brahmins may even vote against their material interests if they believe that their status is under threat. Mobilisation by minorities, on the other hand, demands recognition and representation.

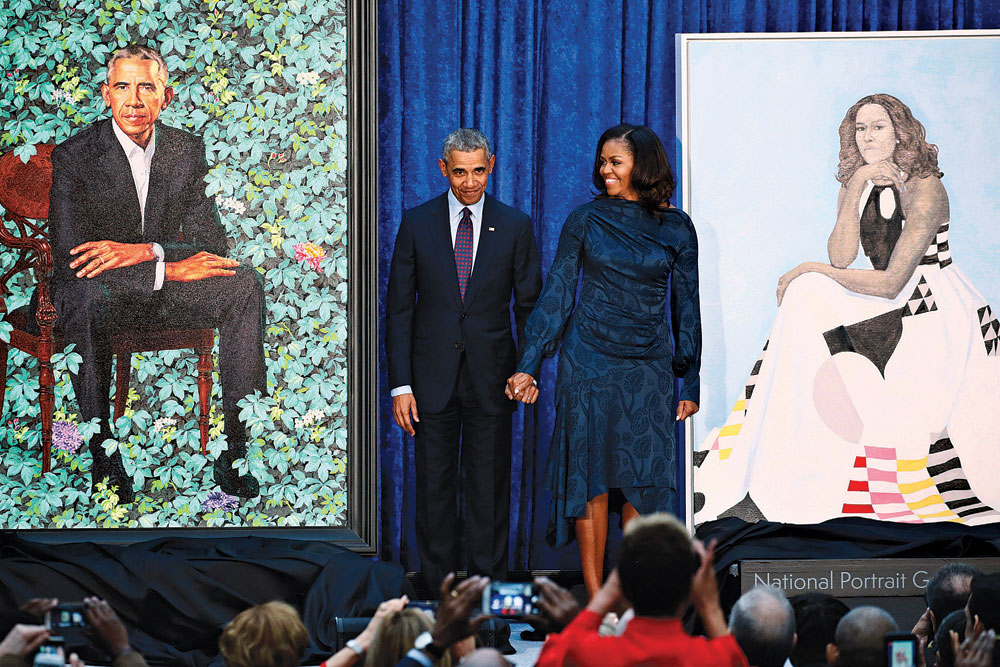

Representation can help reduce self-reinforcing discrimination by demonstrating that all groups are equally capable of high achievement. A photograph of a two-year-old Black girl mesmerised by a painting of Michelle Obama at the National Portrait Gallery that went viral in 2018 illustrates this well

The gains of representation in popular culture and fashion have been widely recognised in the last few years. Representational claims on the state are important so that marginal groups are reflected in institutions of power and seen as legitimate members of the political community. These claims can take several forms. It may mean naming or renaming of streets and public parks after leaders of marginal groups—the memorial dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr at the National Mall or the statue of Ambedkar, India’s most prominent lower caste leader, in the Indian Parliament, for example. It may translate to removing symbols of majority domination, like demands to take down confederate monuments in the American South. Beyond symbolic measures, it may mean that public institutions are more diverse—our legislators, city officials, judges and perhaps, most importantly, our police resemble the identity of the people they are governing. A large body of research finds that representation can have positive implications for policies directed towards marginal groups. Who occupies the state has a bearing on what the state does.

But more than its effects on policy, representation matters because it helps dismantle status beliefs and, in the process, extends the boundaries of social opportunity for marginal groups. It targets societal as well as self-reinforcing discrimination. Representation in public institutions has been shown to reduce social bias and increase support for minority leaders. These findings are consistent with theories of social change by social psychologists that have emphasised the role of greater contact between groups in humanising the ‘other’ and extending the moral circle of our solidarity. The marginal becomes mainstream through its representation in the public sphere. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, is attributed to end slavery in the US and, more recently, popular television shows like The Cosby Show and Will and Grace have helped in reducing prejudice against Blacks and gay people.

Representation can also help reduce self-reinforcing discrimination by demonstrating that all groups are equally capable of high achievement. A photograph of a two-year-old Black girl mesmerised by a painting of Michelle Obama at the National Portrait Gallery that went viral in 2018 illustrates this well. Reflecting on the reaction to the image, the girl’s mother noted that her parents, who grew up in segregated America, could not have imagined a Black president and first lady. She wrote, ‘Only by being exposed to brilliant, intelligent, kind Black women can my girls and other girls of color really understand that their goals and dreams are within reach’. Michelle Obama was aware of the effect that the portrait could have when she spoke at its unveiling, ‘(Girls and girls of colour) will see an image of someone who looks like them hanging on the walls of this great American institution…And I know the kind of impact that will have on their lives because I was one of those girls.’

So, as we confront the enormity of this political moment, what is to be done? Can centuries of injustice be undone? A class-based understanding of social justice is based on equality of opportunity, regardless of an individual’s material endowment. Hence the focus on redistribution, especially public education and universal healthcare. An identity-based idea of justice aims for equalisation of status across groups. It faces the additional burden of fighting bias, both institutional and psychological. Black Lives Matter is encouraging because it is able to gather widespread support across ethnic and class boundaries. Its demands are expansive, targeting both redistribution and recognition. And it comes at a time when other identity-based movements, particularly by feminist groups and the queer community, have made a strong dent in social norms around inclusion. Despite all the catastrophes of this year, we have a lot to be hopeful about.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

On Being Young Surya San

Why Are Children Still Dying of Rabies in India? V Shoba

India holds the upper hand as hostilities with Pakistan end Rajeev Deshpande