Jayashree Chakravarty: Roots and Twigs and Leaves—And Glue

The canvas of Jayashree Chakravarty exudes the organic vitality of solitude

Rosalyn D’Mello

Rosalyn D’Mello

Rosalyn D’Mello

|

13 Mar, 2020

Rosalyn D’Mello

|

13 Mar, 2020

/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Roots-and-twigs1a.jpg)

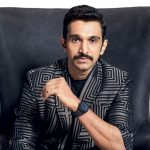

Jayashree Chakravarty in her studio in Kolkata (Photo: Rohit Chawla)

IF THERE’S ONE thing the Kolkata-based artist, Jayashree Chakravarty hasn’t grasped definitively, despite her education at two of the country’s most prestigious art schools—Kala Bhavan, Viswa Bharati (1978), and MSU, Baroda (1980)—the richness of an almost 40-year-old practice notwithstanding, it’s when to refer to a work as complete. Were it not for the cajoling nudges by her gallerists, Reena and Abhijit Lath of Akar Prakar, and the continuing curatorial interventions made by Roobina Karode, it’s possible she might not have felt inclined to let her work leave her studio in Salt Lake City. When I visit her in in September 2019, she shows me a range of unfinished pieces. “There are many incomplete works,” she tells me. “So, you decide, basically, that it’s complete when Reena and Abhijit come to take them?” I ask. She laughs. “I don’t let them in. I send them pictures and tell them what it looks like. Then, accordingly, at some point I feel, okay, maybe it’s done.” This is not to imply that she may not recall a work after it has been exhibited somewhere, or even work on it some more while she’s installing it.

Once, while setting up her works at a space in Mumbai, she was told that the best mode for display involved puncturing holes in the outer edges so each piece could be hung. While this could potentially upset many artists, Chakravarty had zero qualms. She saw it as an opportunity for later repair. “That way I could do some more work on it,” she says.

Her uncertainty with declaring work complete is not a function of the work itself. It isn’t that it bears traces of unreadiness, or even seems unfinished. Perhaps a clue to her desire to continue to proceed is buried within each individual piece which uniquely straddles the lines between drawing, painting, sculpture, installation, often even the architectural. Chakravarty’s process is akin to strategies used by birds to build nests. She evolves a structure through a system of continuous accrual of material, often using glue to bind them together into a cohesive whole. Within a single work, or an installation, she aspires to create an ecosystem, which might account for the dependency on time as unspoken material.

Chakravarty’s practice is invested in a commitment to the meticulous possibilities of process and a wild, unbridled embrace of scale. Yet, her work doesn’t rely on monumentality to elicit an effective response. It succeeds, instead, because she exposes us to forms of fragility. There is an abundance of joy in her approach to work, a seething love ethic.

Visiting her studio revealed to me the role of solitude in her practice, and how inherently her works draw from the powerful integration of her daily experience of domesticity with her artistic subjectivity. “I think all these things happen when you are alone. You can do all kinds of madness, nobody is going to watch you… It’s fun,” she says.

At the time of my visit, Chakravarty had recently set up an area on the ground floor of her home so she could work during her encounters with domesticity. It was a way of returning to drawing through a different existential mode. “Suddenly, I thought, let me start doing something in this space, where I’m busy with normal day-to-day work. Maybe I’m making a cup of tea in the morning and I want to see my work in front of me. So I’m seeing it,” she says. The last time she had ‘worked’ in this room was years ago, back when only this floor existed. “Now, there’s nobody in this house, and I often want to be downstairs, so it’s fun,” she adds, a veiled reference to her ongoing experience of solitude following the loss of both her parents. Her sister, a scientist based in the US, is the one person she speaks to over the phone on a near daily basis. Just outside her kitchen is a table on which I found, besides other edible paraphernalia, a plate of loosely crushed eggshells. In all likelihood these may appear in her works, she frequently relies on the ecru of the shell to create a sheen and supplementary texture. As she brews us a pot of Darjeeling, I survey the threshold between her kitchen and her new working area where surfaces are suspended. There is a porousness between all these spaces; and yet, there is a secrecy to her process.

Until 2009-2010, my oil painting had reached a point where I could do anything-within my limits, of course, not somebody else’s, says Jayashree Chakravarty, artist

ON THE FIRST floor, I witness reams of paper and canvases in states of display and storage. It is in fact a mixture of cloth, paper and colour, handmade by her, using a technique she learned back at Kala Bhavan. I realise that Chakravarty prefers to work on multiple surfaces, mostly because her technique involves accrual, and needs time to set. At the time she said she was waiting for winter to come, she knew she would make a lot of headway during that time. “In three months I’ll progress a lot. By mid next year I’ll complete this.” As she says this, I glimpse another work that bore traces of a structure that vaguely resembled the Taj hotel in Mumbai. I ask her if it was ‘complete’. She says it’s not. “I’ve been doing it since 2006. And then, in between, a lot of things happened and I didn’t complete the work. Now I have taken it out and I will start working on it now. Meanwhile, my work has changed so much,” she says. The image I could glimpse at found itself being articulated by her around the time of the terror attack in 2008. “Now it will start changing. I don’t know if it will remain like this or go beyond it…” she says. Having encountered her work I knew this was not a facetious thing to say, for indeed, the levels of layer upon layer ensured that nothing survived as clear image, while the layers somehow meld into each other to form a holistic surface. “Can you even identify your starting point?” I ask her. “No, not really,” she says.

She then leads me upstairs until we arrive at the second floor, which she has been inhabiting, you can tell, from the way the room is arranged. Like on the floor below, the ground is covered in a layer of paper and plastic. Chakravarty works upon this surface, with her paper spread upon it and her body hovering over. She is extremely agile and credits her daily practice of yoga for her mobility. She laments, though, that her body isn’t as strong as it used to be, which can be a hindrance to art-making, she feels. But as she moved across the room, climbing up and down a ladder to mount her in-progress works so I could see them better, she seemed nimble. She insisted I sit down on a sofa on the other end of the room while she set things up. Once a work was hung, I had the luxury of walking toward and away from it, as she would prefer. I was rewarded with a more sophisticated awareness of the rigorous detailing that is at the heart of how Chakravarty composes her work. Because I was in the space of her studio, I was able not only to confront the fibrous levels of sedimentation of found roots, twigs, leaves, cotton, egg shells, tea stains, and god knows what else, I was also encouraged to touch it. This contact through fingertips revealed a tactility I had gleamed without having had the opportunity to really fathom. It felt sculptural. It became suddenly obvious to me how much her own body makes contact with her work. Even now, as she was laying works on the floor as she took them off the wall, I witnessed her lifting them over her head, holding them with her hands, supporting the centre on her back. At moments, from certain angles, it seemed as though she had been swallowed by her work. When I wasn’t distracted by the shape and form of her as she stood encased in her creation, I saw light streaming through the various layers and noted how she transforms negative space to achieve luminescence.

I ask her about how she achieves this effect of irradiation. She responds by telling me about how she was in fact even better at it in the past. “Until 2009-2010, my oil painting had reached a point where I could do anything—within my limits, of course, not somebody else’s,” she says. “Whatever I liked, I could apply it. It was not something to feel proud of. It happens, you’re thinking like this and you’re able to do it. I’ve lost it. It’s no more with me. The kind of thing happened in my life with my mother’s illness, I forgot it. My painting changed, I couldn’t do it any more. I totally forgot it.” Between 2010 to 2015, Chakravarty had become her mother’s primary caregiver when she began to suffer from dementia, coupled with blood sugar-related skin problems. “She was taking steroids. I was putting ointments, preparing it with other powders… This was a kind of real engagement.” Perpetually unsatisfied by unskilled nurses, Chakravarty, whose doctor father had taught her early in life how to make bandages, and how to attend to illness, decided she wouldn’t allow anybody else to touch her mother besides her. “These five years were something else for me. I forgot many things, washed it off. Now it’s coming back… how I used to use paint.” Around 2016, she started working with paper again, like she did, back in 2001-2002. “I was doing even bigger things, from 1991… With handling oil paint, you need an immediate skill.” Chakravarty admits she does feel inclined to take a brush and use oils again. “Something is inviting me, and I feel like doing it,” she says. But she laments her body’s weakness. “In the past years I’m not that strong any more. I do a lot of things that need strength.”

AT THE CORE of Chakravarty’s current practice is an ecological concern for the growing disappearance of the city’s tree cover. Her father had a green thumb, the one that remains of what he planted is a black jamun. She laments that most city dwellers, including her neighbours, now see trees as a nuisance, because the shed leaves occupy space, or the fruit stains the ground. It’s the same situation with the jamun. But because the fruit is very sweet, “everybody loves it.” Her work is a way of preserving the roots that are being severed, thanks to urbanisation. When she first moved to Salt Lake she remembers sand and tall grasses. “Then it started changing. Then there were some trees, but everything was taken out, because a concrete jungle had to be established. All the trees were soon gone. The whole of Salt Lake has changed, also, next to it, New Town. Salt Lake was a huge water body, very necessary for Kolkata. Then a decision was taken to build a new city. That’s how it changed, this area, and that’s how it changes everywhere in the world. I’ve witnessed it. Others have witnessed it elsewhere.” The ecological impact of the felling of trees manifests through scattered rainfall in Salt Lake. “The weather is changing drastically,” she says. “The roots of trees hold the earth and doesn’t allow it to get eroded. This is another important thing… So I’m looking at roots, how they networked with other trees.” Chakravarty uses charcoal, water-based and oil-based pencils and water-soluble lead. When she needs to use white, she prefers acrylic.

People often ask her if her work will last, considering the bizarre array of found materials she uses. She doesn’t honestly know. “My body is not going to last, that I know. That’s guaranteed, the rest is not.” Part of the reason why her work takes so much time is because she is constantly using glue (Fevicol), which needs some time to dry, and for the new surface to be revealed. Because she prepares paper herself, mixing it with cloth, it becomes leather-like, even breathing differently with change in weather, while the glue is constantly responding to varying humidity levels.

Chakravarty describes these aspects as the best thing about her work. “You feel it. It has its own energy.” This organic vitality is the consequence of her spending time with the work’s incomplete-ness, evolving a relationship with it, living the experience as an extension of breathing. Therefore, for her, scale has been internalised at the level of intuition, and as a method of actively studying her subject material, thus allowing for immense, prolific detailing. All this and more is revealed to the viewer who encounters the work from different angles and distances. “Suddenly you see the work in a different light, it says something else,” she says. “I find it is very alive.”

(Jayashree Chakravarty’s work can be viewed at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, Saket, Delhi, as part of the ongoing show, Abstracting Nature: Mrinalini Mukherjee and Jayashree Chakravarty, curated by Roobina Karode. It runs until June 30, 2020)

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai

Love and Longing Nandini Nair

An assault in Parliament Rajeev Deshpande