A few days after the arrival of Margazhi, a month in the Tamil calendar, that also marks the annual season of music and dance in Chennai, the fourth edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale (CPB) inaugurated one of its invited projects titled Madras Margazhi by Chennai-based photographer and entrepreneur, Amar Ramesh. Mounted at Chennai’s prestigious cultural institution, Narada Gana Sabha, a hub for the classical arts, Madras Margazhi is a showcase of 50 photographs of Carnatic musicians such as veena player Ramana Balachandran. multi-percussionist Praveen Sparsh, and violinist Lalgudi GJR Krishnan, to name just a few.

From amongst the images that dress the bay windows, there is a photograph of Vyasarpadi G Kothandaraman playing his nagaswaram against the backdrop of the lighthouse that is a landmark on Chennai’s Marina Beach. Dressed in a traditional dhoti, complete with an angavastram, standing tall and playing this double reed wind instrument from South India, the contrast of the horizontal and the grand vertical backdrop of the lighthouse, is simultaneously striking and humbling. It is a reminder of how intrinsic and essential both music and the Marina are to the fabric of Chennai. In black and white, and with unfussy minimalism, the image reminds us of the Madras and the Margazhi way of life. “I believe artists are like athletes,” says Ramesh, “They put in hours and years to fine-tune their craft; I wanted to portray that spirit of endurance and give them the star-like status they richly deserve.”

On the other side of the city, early this year, nearly 7,000 people walked into the city’s mall VR Chennai, in Anna Nagar West, and witnessed Vaanyerum Vizhuthugal (meaning Roots that Reach for the Sky in Tamil), which is CPB’s primary show that will run through until the end of phase three in

March. Located in the atrium, this exhibition, curated by Jaisingh Nageswaran, is, as its name suggests, is both inward-looking and universal.

Featuring the work of 12 lens-based artists of Tamil origin, the exhibition is an ode to the Tamil wave that is distinct but also diverse. In As Close as It Gets, Chennai-based visual artist, Vivek Mariappan reconnects with his hometown Erode, in Tamil Nadu, by photographing its people and the environment. We meet a woman dressed in a nightie (an attire for women that is at the intersection of leisure and labour) standing against the backdrop of paddy fields under a dark blue sky and staring into nothing. Mariappan allows his viewers to recognise a little bit of their own selves in his personal quest to find his bearings.

On the day that we visit VR Chennai, there’s a small crowd milling through this exhibition; some casually take in the work while some others rest at particular photographs. Every viewer has their own response to a photograph, right, we ask Varun Gupta, co-founder CPB and the Biennale director. “Placing photography in a public space has its own fair share of challenges. Everyone has their own response to the way they navigate exhibitions like these and it’s okay. For us, this is the possibility of putting out ideas and issues that persist in the world through the medium of photography,” he says.

In this edition, in particular, a distinct idea—why photograph—that draws inspiration from leading photographer Dayanita Singh’s ongoing exploration of ‘#whyphotograph’ becomes the umbrella under which ideas find expression. As Gupta says, “In the world that we live in, the ‘why’ of everything has become very important. Everyone is participating in this ecosystem of photography. We photograph everything—sometimes without even realising it—in a manner that has almost become an instinct today; it’s like eating, breathing, sleeping.”

In an endeavour to inquire into why photographs are made, and to investigate what prompts artists to photograph, CPB4—featuring 25 exhibitions—is mounted across galleries, parks and public spaces to allow everyone to engage with photography. It also brings to fore an assemblage of ideas—caste, politics, gender, resilience, hope—by artists from Chennai, India and across the globe.

To enable engagement in a slow and sustained manner, CPB unfolds over three phases. As Katharina Goergen, director, Goethe-Institut Chennai that co-founded the Chennai Photo Biennale, says, “Photography has the capacity to create awareness or beauty; it can produce memories and disrupt the present; it can be a tool to document, to tell a story or to create art.”

In the last week of January, British Canadian citizen and independent photographer, Sunil Gupta’s first-ever retrospective in India, titled Love & Light, curated by Charan Singh, was inaugurated at Chennai’s Government Museum located in Egmore. The work of Delhi-born, Gupta’s queer photographic practice is both tender and powerful, seen poignantly in his photo of two men in a coy embrace standing by Delhi’s India Gate.

The Egmore Museum is also host to the children’s showcase titled What Makes me Click! that features 20 projects by children between the ages of 4 and 18 from across the world. Gayatri Nair, co-founder, CPB and Director of Education, CPB4, says, “This showcase, curated by CPB and the Children’s Photography Archive allows for the possibility of seeing a child’s world; it’s the possibility of looking at what do they do when they are given the camera. When they are four or so, they photograph their feet, the sky, the stars; as they get older, they start looking around—neighbours, community, nature, climate change, issues, causes etc.”

Equally arresting is an exhibit titled Gaza Seen by Its Children with Belgium-based artist, Asmaa Seba. To help heal children who witnessed the massacres during an Israeli operation, artist Seba spent three months in 2012 with children and offered them a balm called photography. In bringing their stories to the fore and celebrating their bravery and courage amidst what Seba says was an “open air prison” is a testament to the power of photography to heal.

In Ahel el-Ard, that is part of It’s Time. To See. To Be Seen at the Lalit Kala Akademi, Palestinian photographer, Samar Hazboun presents a poetic way of Palestine life, celebrating people and their relationships with their land. In one photo a veiled woman tends to her olive tree, in another a bare-chested man lies supine on a chair out in the open, as if he has surrendered to the earth.

Closer home, in the same show that brings together women responding to the world through photographic practices, Unequal Heat , an arresting series by Delhi-based artist, Bhumika Saraswati, reveals the lives of marginalised women. Raised in a Dalit household by her single mother Gita, Bhumika’s work forces you to sit up and look at the inequalities in our world. The image of one woman dressed in a t-shirt and jeans with her hair open braiding another woman’s, dressed in a salwar kameez, demonstrate how tradition and freedom exist in harmony. These photos show us a private world in a searing way.

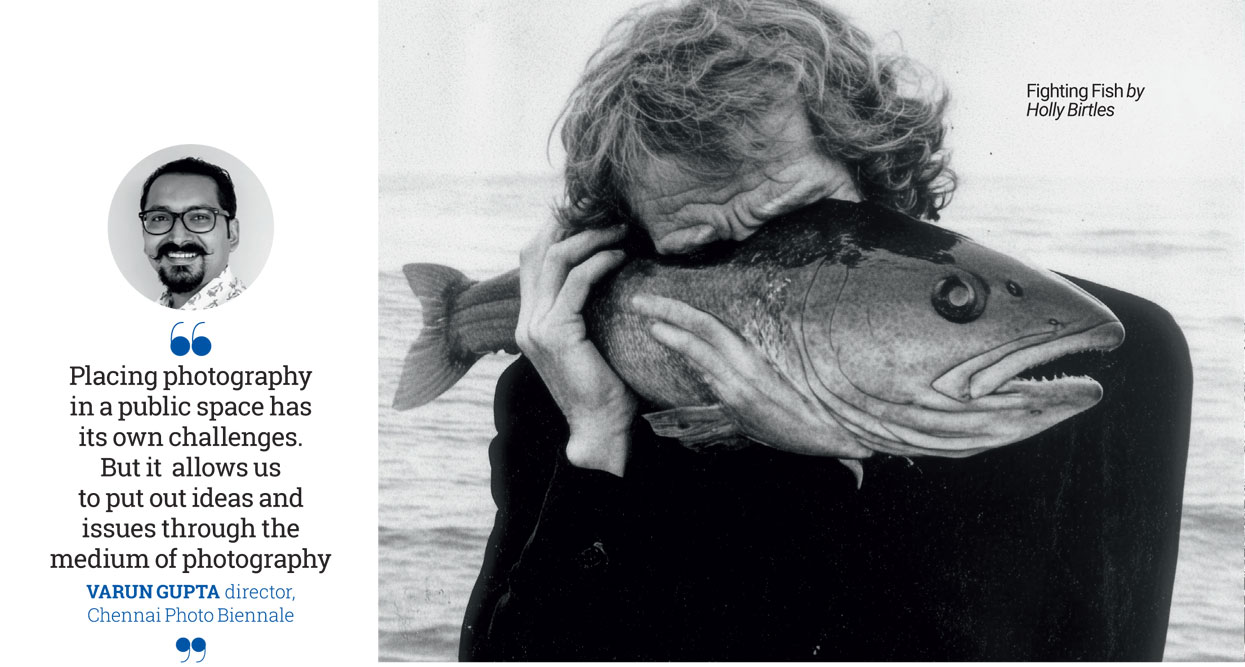

UK-based artist Holly Birtles engages with the Adyar and Cooum rivers, in her project Fighting Fish that intertwines magnificence and the grotesque, leading to semi-fictitious life forms that tell of the relationship between people, rivers and creatures.

In many ways, the biennale is about this—stories; the stories of stories; personal portraits that have universal resonance; the opportunity to see someone and the lens through which they perceive the world, and how that perception can help shift our own perceptions of the things we see and will see.

Under the umbrella of Vaanyerum Vizhuthugal, Chennai-based lens artist, Aishwarya Arumbakkam, creates a gripping photo essay on Indian hair. In her photos, the hair becomes the face of women. As a metaphor for identity, resistance, vulnerability and manipulation, this deep dive into the world of hair is more than just about the length, style and texture. Some women have their hair open and flowing down their backs; we meet hair that is plaited tight; there is hair bound into an intricate bun that covers the nape of their neck. Arumbakkam says a commissioned project for a publication led her into a deeper engagement with investigating women’s hair, the stereotypes that exist within, how hair often plays a crucial role in building our sense of identity and the many frictions that are attached to it; how hair can be manipulated as a marker of beauty and above all, the emotional connection that a woman shares with her hair. “There’s more,” Arumbakkam says. “And this is only a work-in-progress.” A reminder that every kind of hair style has a story of its own, and every gaze matters.

(Chennai Photo Biennale runs across the city till March 16)

More Columns

Seven common myths and misconceptions about sleep debunked! Dr. Kriti Soni

Ranveer Allahbadia: Laugh Track or Attack? V Shoba

The Next Moves in Manipur Siddharth Singh