The London Connection

A new collection of essays shines a light on BR Ambedkar’s internationalism

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Londonconnection1a.jpg)

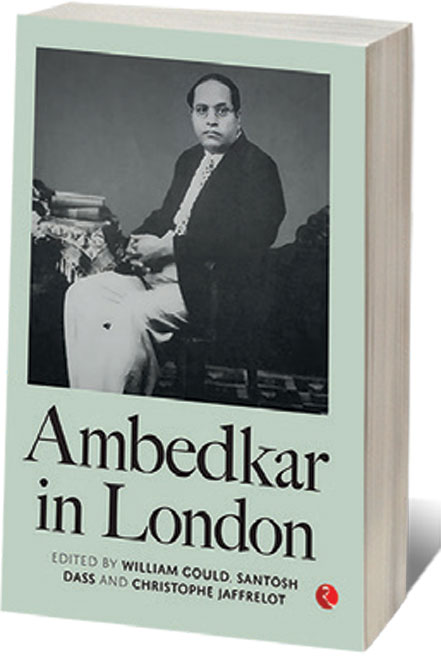

BR Ambedkar (Photo: Alamy)

AMBEDKAR IN LONDON is quite unlike the usual mould of research on BR Ambedkar. This one focuses on his internationalism in the 1910s and 1920s. It is a lesser-known aspect about the man who, in the words of scholar Suraj Milind Yengde who wrote the foreword for this book, “chose London as a place to secure rights for his people”, meaning the Dalits. The two Western cities that shaped Ambedkar’s life, New York and London, influenced him in different ways. As Yengde rightly points out, it was in New York where the young Ambedkar nurtured his intellectual activities and academic growth, but London was where he began to put his ideas into action.

This book, a collection of essays by academics of repute and co-edited by William Gould, Santosh Dass and Christophe Jaffrelot who have also contributed to this insightful work, draws on new material available from institutions and places that Ambedkar was associated with. It captures how the making of latter-day Ambedkar was embedded in his work and activities in the capital of the British Empire, during and after World War I.

Reading these essays is quintessential to understanding the roots of Ambedkar, one of India’s greatest intellectuals whose thoughts continue to inspire the masses as well as scholars. No less a scholar than Perry Anderson had noted that Ambedkar was intellectually head and shoulders above most of the Congress leaders of the freedom movement and that to read Ambedkar was “to enter a different world”. Besides, long after his death in 1956 aged 65, his political ideas help mobilise movements of the weakest sections of society.

In their introduction, Dass and Gould outline the purpose of the book—which was to dig deep to uncover the roots of Ambedkar’s thinking in “key texts such as Annihilation of Caste, and in the central constitutional position of Schedules Castes or Dalits.” These texts were rooted in Ambedkar’s earlier work around “caste, labour, governance, the economy and representation from his time in London as a PhD/law student in the early 1920s”. They also argue that “Ambedkar’s oeuvre and political experiences were shaped, both directly and inadvertently, by his time in London and by his connections to the city”. What is clear from these studies on Ambedkar is that he used international networks and non- Indian contexts to fight for the cause of the Untouchables. And that he was influenced by the interwar political theories and ideas of the economy. How Ambedkar’s international career in the 1920s “shaped approaches to Dalit rights in the UK” and globally also comes to the fore. Ambedkar was a student of Columbia University from 1913 to 1916 and spent time in London studying law from 1916 to 1917 at Gray’s Inn, which he had to end within a year before he returned to the city in the early 1920s, mostly at the London School of Economics (LSE) for his studies for an extended period.

In his essay, Gould offers a glimpse into the life of Ambedkar as an activist research scholar in 1920s London, his associations and where he had lived and so on. It also delves into his life at 10 King Henry Road in North London, which has now been converted into a museum. It also demystifies a woman in question named Fanny Fitzgerald with whom the young Ambedkar, according to some biographers of his, had a romantic relationship. Ambedkar had dedicated to one ‘F’ his book titled What Gandhi and the Congress Have Done to the Untouchables (1945). But Gould’s essay, after extensive research, finds incongruities in such claims and comes up with other possibilities. It argues that it is not productive to speculate about the “full nature of his relationship to F”. The essay goes on to dwell at length on ‘The Problem of the Rupee’, Ambedkar’s doctoral thesis written in 1922-23 and later published as a book. Gould notes, “The sheer ambition of Ambedkar’s London PhD, as the only work of the time, aside from that of Keynes, to fully explore India’s gold exchange standard, was also reflected in the style of research he must have undertaken. The text is punctuated throughout with long and detailed quotations from official reports, India Office archival materials and published sources from contemporary economists.”

In the second chapter, Sue Donnelly and Daniel Payne use archival records to portray a stark picture of Ambedkar as a student at LSE, where he had returned in 1920 thanks to funds offered by the Maharaja of Kolhapur who they say shared Ambedkar’s opposition to the Hindu caste system. He had to return to India in 1917 on the expiry of a previous scholarship to serve as the military secretary in Baroda.

What is clear from these studies on Ambedkar is that he used international networks and non-Indian contexts to fight for the cause of the untouchables. And that he was influenced by the interwar political theories and ideas of the economy

The writers offer new perspectives about Ambedkar the student. “Ambedkar’s student file does not cover the process of undertaking the research for the DSc or include any correspondence with his supervisor, Edwin Cannan… Later in the file, a letter… reported that Ambedkar submitted his DSc Economics thesis in October 1922, and it was examined in March 1923… Ambedkar resubmitted it in 1923 and his degree was conferred in November 1923. Some accounts claim that the thesis was initially rejected for its anti-British or anti-imperial content— but neither the student file nor the correspondence with the University of London provide evidence for or against the claim,” Donnelly and Payne write, and present proof about Ambedkar’s continued ties with LSE even after his return to India. Steven Gasztowicz’s chapter looks at Ambedkar’s legal education and puts in context what all had to be done to become a barrister back then and about his experience as a practising lawyer.

The other chapters in this book explore how Ambedkar used the Indian Round Table Conferences in London to internationalise the problem of untouchability in the 1930s. Jesús F Cháirez-Garza writes, “I will argue that Ambedkar used these gatherings as a stage to present the plight of Dalits to an international audience beyond the subcontinent. In particular, Ambedkar used the political structures and technologies in place to sustain London as an imperial capital and centre of power to move the question of untouchability from being considered a socio-religious issue into a political question.” There was a reason why he did it, and Cháirez- Garza explains, “…London not only represented access to British political figures who had an important say about the future of Dalits, but the city also became a space where the rules of caste could be relaxed….”

In his essay, Jaffrelot captures Ambedkar’s political trajectory as he travelled back and forth between India, the US, the UK and even Germany. His fight against the caste system, the author says, oscillated between two poles—within the existing order or against it—and he finally moved from one pole to the other. Jaffrelot talks about how Ambedkar himself viewed his social-reform strategies from a global and historical context. Jaffrelot adds, “The 1920s saw the transition of Ambedkar from rather limited demands to the making of a programme based on equality and liberty.” The quest for equality became the cornerstone of what became a new ideology: Ambedkarism.

The book goes beyond London and emphasises his cause to internationalise the Dalit cause, its impact on the Dalit diaspora, about the Ambedkar Museum, and his correspondence with luminaries who identified with his political mission.

This work is not only a rich tribute to Ambedkar’s early efforts to develop political strategies while he was still a student, but it is also an effort to bridge the gap between what is known and not known about a tall intellectual who acquired a brighter halo and renewed political significance decades after his death.

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Cover-ModiFaith.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Syeda-Saiyidain-Hameed1.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Memories1.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/SaltandSand1.jpg)

More Columns

Controversy Is Always Welcome Shaan Kashyap

A Sweet Start to Better Health Open

Can Diabetes Be Reversed? Open