Between Death and Democracy

Kashmiris take to the elections with great fervour. Is it an endorsement for New Delhi? Rahul Pandita travels across Jammu & Kashmir

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

|

13 Sep, 2024

|

13 Sep, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Kashmir1.jpg)

A BJP supporter wearing a Modi mask near party candidate Engineer Aijaz Hussain’s house on the outskirts of Srinagar, September 4, 2024 (Photos: Ashish Sharma)

IN SRINAGAR, PEOPLE WHO WIELD REAL POWER NEVER DRAW ATTENTION to themselves. It has always been like that. When they move around, they do so discreetly. In a place where nothing escapes the gaze of the anonymous, they conduct their business without the loudness of pilot cars, jammers, and armed guards.

The new errand boys of nationalism in Kashmir, however, appear in all flashiness across the city. You see them in the new cafés around the smart-city part of Srinagar, having their cappuccinos, and charred meat and bread, always measuring up customers who enter after them. They speak in hushed tones while their bulletproof Scorpios and bored police guards wait outside. Behind them is the Jhelum riverfront, where young men smoke and watch Instagram reels, and pre-diabetic Kashmiris take walks. Some of these errand boys are ‘journalists’ whose bylines appear in ether; some are ‘experts’ who never venture beyond the two-square miles of Gupkar Road, while some are young men (and women) groomed as future politicians by Army generals whose PPTs have quotes from Malcolm Gladwell—they say “Jai Hind” when they take leave of you. “Here, have a little papaya,” says the police officer, who knows them all. His eyes are puffy, a result of too many forced late-night dinners that his seniors masquerade as security-review meetings. The errand boys often sit for hours outside his office; they need things that will make them look important—things like police protection.

“I entertain them only when I get a go-ahead from above,” he says. Otherwise they keep sitting on vomit-brown plastic chairs linked to one another in corridors, watching with jealousy the chosen ones who get to meet officers behind walnut-wood screens. It is a cycle. They make themselves useful first or express a desire to be useful. If they get noticed, the officer will be asked to pay attention to them. Once they are deemed important, they become more useful; at least that is the impression they want to exude. Sometimes they come just like that, hoping to get things without asking. “They say, ziarat karne aaye hein (we have come to pay obeisance). And I am like, m***** f******, what do you think I am? A mausoleum or what!” the police officer says.

It would perhaps take a Deleuze to make sense of the Kashmiri psyche—every doctrine, every manual to predict how the Kashmiris will behave, has come a cropper. It is surreal to see a cavalcade of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) supporters, some of them wearing Modi masks, passing through the main market in Shopian town—a town where four of Burhan Wani’s batch of 11 boys were killed by security forces. In 2016, the situation was so tense here that even police officers hardly ventured out. On the road where you would be surprised if you did not witness a hand-grenade attack, there are men today seeking votes for Modi. “We are in the habit of saying that Pakistan failed Kashmir. But the truth is that Kashmiris failed Pakistan,” the officer says. He is looking at the wall clock on his left; there is another meeting to attend shortly. “If I were the ISI [Inter-Services Intelligence] chief and saw a boy wearing a Modi cap in Shopian, I’d drown my sorrow in whisky,” he says.

“I remember them [mother Mehbooba Mufti and grandfather Mufti Mohammad Sayeed] having disagreements; they were not on the same page. But what Mufti Sahab had in mind was the BJP run by Vajpayeeji. He remained an Indian at heart, not by convenience like so many others here,” says Iltija Mufti, PDP

It is not that terrorism is over for good. The new-age hybrid militants who will receive a target on Telegram messenger and a YouTube link on how to unpin a grenade or how to fire a pistol are around; and so are a handful of Pakistanis, in places like Kokernag in the south and Lolab Valley in the north. They probably walk around, clean-shaven, in jeans and tees, wondering like many others what to make of the Kashmiris they were told were mazloom (oppressed) and who are now out in droves, cheering for politicians who keep bringing up the Indian Constitution in their speeches. Many men who are dancing in front of election rallies, enduring the harsh sun for hours, are also the ones who had run in hypnosis after the long-haired ‘Hanzila bhai’ and ‘Saifullah’, desperate to touch them and kiss their hand. They opened their houses for those who came from across, cooked for them, pelted stones so they could get away, and mourned for them when they were killed. But among the mourners there would also be a man, perhaps beating his chest more steadfastly than others, who would have the previous evening given away the terrorist’s location to his contact in the police or the Army. One has met them in Shopian itself; for one such giveaway, a man like that once asked for `15 lakh from the Army and when the cash was put in front of him he became nervous and asked instead for gold jewellery equivalent of it, so that he could make his wife wear it under a burqa and send her off to Jammu.

Between mourning and celebrating, between death and democracy, Kashmir keeps oscillating. And as it does so, it defies all singularities, or for that matter any articulate framework. Today, people who come out dancing for their candidates will burn their effigies tomorrow and hit their posters with shoes. The flip from reverence to rejection has been the fate of Kashmir’s tallest leaders like Sheikh Abdullah and Mufti Mohammad Sayeed.

“I did not give it much thought because [Rashid] Engineer had contested previously as an MLA from the area. But subsequently we saw that his party admitted people who have been strong votaries of BJP. And then Barkati—he was made to fight from an area where he has no connection,” says Omar Abdullah, National Conference

It is this thought that weighs heavily on Iltija Mufti’s mind as she rises through the sunroof of her car in South Kashmir’s Bijbehara, a seat which her grandfather won for the first time in 1962 and later her mother in 1996. It is from South Kashmir that the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), a party formed by Mufti in 1999, offered an alternative to the oldest mainstream political party in Kashmir, the National Conference (NC). But this is a time when PDP is perhaps at its lowest—a result of people’s anger about the party’s decision to form an alliance with BJP, an alliance which was unceremoniously called off by BJP after Mufti’s death. “I remember them having disagreements; they were not on the same page,” Iltija says of her mother and grandfather on the decision to go with BJP. “But what Mufti sahab had in mind was BJP run by Vajpayeeji. He remained an Indian at heart, not by convenience like so many others here.”

Iltija’s car is surrounded from all sides by PDP supporters. The cadres sing, accompanied by a Kashmiri musical instrument, in the front, shouting, among others, a slogan that speaks about how hardship disappeared whenever a Mufti arrived. Iltija’s close aides ride outside the car, beyond which is a cover of policemen and paramilitary soldiers. Every now and then people throw candy at the car to welcome her, which makes her security nervous. It also hits her eyes sometimes, after which she flinches but carries on. “Thirty years ago, my mother took the first step, and now I am. I know you love me—a little, not much, but you do,” she tells people. They shout back in unison that they love her just like they loved the two previous generations of the Muftis. An elderly woman, barely four feet, takes her hand. “You won’t remember me, but I am the first one to vote for you,” she says.

Tarigami is perhaps the only candidate who speaks about Kashmiri Pandits from conviction. That is not an easy task today. He remembers when armed men came to his house. He ran away and took refuge in Jammu at a Pandit’s house. ‘In a way you can say that I was the first migrant,’ he says

In the middle of the campaigning, a man among the crowd gets angry. “Please come out first and address your people, you can speak to journalists later,” he says. “You cannot speak to me like this,” Iltija ticks him off with controlled anger. Chastised, the man sulks and melts into the crowd.

“I get this mansplaining at times. They love me, but sometimes a lone man somewhere will infantilise me. It is because I look younger than I really am,” Iltija, who is 37, says. In a state where women do not have enough role models, the young in Dirhama village gravitate towards her. They push through crowds to shake hands with her, and click selfies; they watch her intently as she waves at people, adjusting the dupatta over her head. But once she is inside the car, she drops it. “I don’t want to be hypocritical about it. In real life, I do not cover my head. In villages it is a cultural thing and I respect it,” she says.

For winning though, in the post- Article 370 Kashmir, Iltija is perhaps aware that she will have to reach out to people other than the core PDP loyalists. “Politicians are also humans. If we have made mistakes, if Mufti sahab has, if my mother has, then I am seeking your forgiveness,” she tells the crowd.

That forgiveness may work if a message that has been doing the rounds in Kashmir this month percolates deep down. The message is about the ‘conspiracy’ of the independents. These are candidates fighting independently, but many in Kashmir believe they are doing so at the behest of New Delhi to cut into the votes of both NC and PDP, although in the current scenario BJP seems to be keener to cut NC to size than PDP. Prominent among these are the candidates fielded by the jailed separatist leader Rashid Engineer’s party—he has been granted bail to campaign in Kashmir. The banned Jamaat-e-Islami is also backing four of its members as independent candidates.

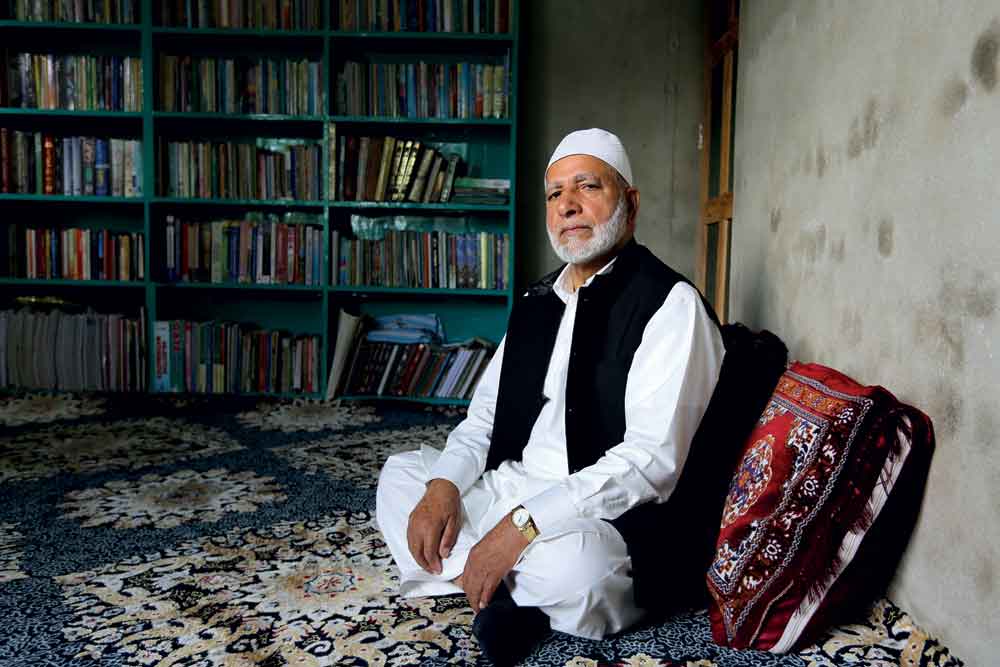

THE JAMAAT’S ELECTORAL participation began through the Panchayat in 1969. In 1971, it contested the Lok Sabha elections from Baramulla. In the 1972 Assembly elections, five people from Jamaat won, including the late separatist leader, Syed Ali Shah Geelani. In 1977, one Jamaat candidate was elected. In 1979, however, Jamaat faced a severe backlash after the hanging in Pakistan of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Holding their ideology responsible for it, the Jamaatis were attacked across Kashmir. More than 500 houses and dozens of orchards and factories belonging to its members were burnt down or destroyed; at least one member lost his life.

Jamaat’s four candidates include Ghulam Qadir Lone’s son, Kalimullah, 35. Lone feels Jamaat was targeted disproportionately in the decades of militancy. ‘All those who had taken up guns did not belong to Jamaat alone,’ he says

In 1987, the party’s general secretary, Ghulam Qadir Lone contested under the banner of the Muslim United Front, a coalition of Islamic political parties, and lost by 700 votes to the NC candidate. As the elections were believed to be rigged in favour of NC, it further precipitated the anti-India sentiment in Kashmir and finally led to militancy in 1989-90. Initially, Jamaat kept out of it. But soon afterwards, it became the fountainhead of the biggest Pakistani-backed terrorist outfit, Hizbul Mujahideen. It faced a ban in 1990, and Lone himself spent time in jail between 1993 and 1996. From 1990 onwards, Jamaat called for a boycott of any electoral process in Kashmir. In the Kashmiri political landscape, extremists like Geelani took precedence, leading to the formation of the Hurriyat Conference, a pro-separatist conglomeration of parties. In 2019, days after the Pulwama suicide attack, Jamaat was banned once again in Kashmir; its bank accounts were frozen and hundreds of schools it ran were ordered to shut down. Lone himself spent eight months in jail in Allahabad as one among many picked up days before the scrapping of Article 370 later that year.

Jamaat’s four candidates include Lone’s son, Kalimullah, 35, who holds a Master’s in computer science. Lone feels that Jamaat was targeted disproportionately in the last three decades of militancy. “All those who had taken up guns since 1990 did not belong to Jamaat alone,” he said at Ananwan village in Langate in North Kashmir.

In South Kashmir, Jamaat-backed candidate Sayar Ahmad Reshi tells voters, ‘come out and vote and if anyone tries to stop you, grab him by the collar and take him to the police station’

In the neighbouring village of Batpora, Kalimullah Lone sits at a supporter’s house, discussing his campaigning strategy. He remembers the time his father was picked up in August 2019. His daughter was five years old then, and the incident, he says, has left her scarred. “I had to take her to a psychiatrist who advised us to explain to her why her grandfather was picked up like that,” he says. Like his father, Kalimullah now hopes that the ban is lifted. He says it is only through teachings at Jamaat schools that youngsters in Kashmir can be persuaded to stay off drugs. A young man was found dead in an orchard nearby due to a drug overdose; somebody else killed his mother under influence.

At the other end of Kashmir, in the south, the other Jamaat-backed candidate, Sayar Ahmad Reshi, sits in his jeep in Kulgam, on his way to Checkpora village. A young woman comes out of a house and offers him juice. Young men wearing T-shirts that read “Sayar Sir” on the back guide his campaign route. As the jeep comes to a stop, his security in-charge stops him from getting out immediately. Around five policemen with friskers run them in the vicinity of the jeep, around stationary bikes and at corners, to check for explosives, after which he steps out. “Come out and vote and if anyone tries to stop you, grab him by the collar and take him to the police station,” he says in his speech. It is also surprising to see him talk about the return of Kashmiri Pandits. “A garden only becomes a garden when it has different flowers. The Pandit brethren are a kind of flower in our garden. I appeal to them to return,” he says. It does not evoke any response from those who have stopped to listen to him.

“We want the dynastic families who ruled Kashmir for so long to be out and make way for peace-loving politicians who do not endorse terrorism,” says Ram Madhav, BJP in-charge of J&K

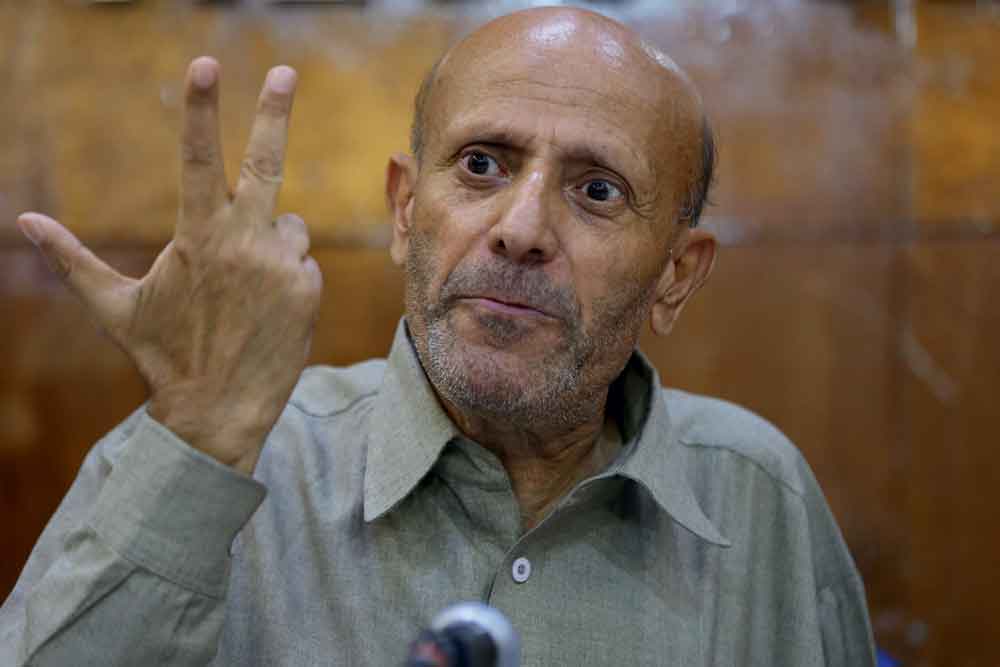

A few miles away, the lone communist leader in Kashmir, Mohammed Yousuf Tarigami, addresses a small gathering at Ramgarh village. “We are not in the business of barood (explosives), we want our young men to be released from jails,” he thunders. Tarigami, who has won the Kulgam seat since 1996, has faced a formidable enemy in the form of Jamaat. In the 1980s, communist cadres under the leadership of Tarigami fought many a battle with the Jamaat cadre. In one instance, this fight took the form of a violent confrontation along a river, with both sides hurling stones at each other. Tarigami won the Kulgam Assembly seat in 2008 and 2014 too, but with a narrower margin. This is attributed to Jamaat cadres voting for the PDP candidate.

In his speeches, Tarigami often uses the secular vocabulary of Kashmiri syncretism to drive across his message. In Balpora, addressing a crowd, he says, “Our fields do not grow grenades, but sweet apples. Let us not forget that.”

Tarigami is perhaps the only candidate who speaks about Kashmiri Pandits out of conviction. In today’s Kashmir, that is not an easy task. He remembers the time towards the end of 1989 when Mufti’s daughter, Rubaiya Sayeed, was kidnapped. He remembers being unwell one day around that time when armed men came to his house. He ran away and took refuge in Jammu at a Pandit’s house. “In a way you can say that I was the first migrant,” he says.

ON SEPTEMBER 8, NC’s Omar Abdullah drove with his entourage to address a series of rallies in Shopian. By his side was Aga Syed Ruhullah Mehdi, the Lok Sabha MP from Srinagar. The heavily sanitised route passed through Kakapora where the Pulwama suicide bomber Adil Ahmad Dar lived. In the orchards, workers were busy picking apples and sorting and packing them in boxes under makeshift tents made of blue tarpaulin. Behind them, deep in the orchards, one came across a company of Army personnel in camouflage and SOG personnel of the police in their black uniform.

Omar’s first address was for Sheikh Mohammed Rafi, NC’s candidate from Shopian. In a small ground, about 300 people, mostly men, had gathered. The premises had been secured by paramilitary soldiers who also kept watch from buildings in the vicinity. Omar made it a point to convey to people how the independent candidates had been pitted against him. “They have sent everyone after me,” he said, “somebody arrested them, somebody else pressed charges, and now suddenly they are fighting against me.” It is the candidature of the separatist Sarjan Barkati that Omar says set the alarm bells ringing for him. Barkati, who is in jail for allegedly raising funds for terrorists, is from Shopian but was allowed to file his nomination from Ganderbal, Omar’s constituency. Omar says he did not suspect when Rashid Engineer was fielded against him in the Lok Sabha polls (which Engineer won). “I did not give it much thought because Engineer had contested previously also as an MLA from the area. But subsequently we saw that his party admitted people who have been strong votaries of BJP. And then Barkati… you made him fight from an area where he has no connection,” he said.

BJP seems keener to cut NC to size than PDP. Prominent in this are the candidates fielded by the jailed separatist leader Rashid Engineer’s party—he has been granted bail to campaign in Kashmir

Which argument people buy and where in Kashmir is unclear. Things change every day and no one is sure which side the dice will roll. The independents are trying hard to convince people that they are not ‘collaborators’ whereas the other side is trying to hammer in exactly that theory. But most people believe in the likelihood of either of the two following scenarios: BJP gets adequate seats in Jammu region, spoils the chances for Omar and others, and then cobbles together enough seats from Kashmir to form a government. Or the belief that the independents are BJP’s collaborators becomes so widespread that most of them are rejected, paving the way for NC to at least play the role of kingmaker, if not win an outright majority. In Kashmir, BJP has fielded its candidates for the sheer symbolism of it and to encourage cadres, looking at a long-term stake in the Valley’s politics. One of these candidates is Engineer Aijaz Hussain who is fighting from the Lal Chowk constituency. On September 4, BJP’s election in-charge, Ram Madhav, visited Hussain’s residence in Balhama to prop him up. Nobody in BJP believes he will win, but for the party, people in Kashmir openly endorsing Modi’s name is enough for now. As Madhav entered Hussain’s house, his supporters wearing BJP caps and taking selfies with a Modi poster shouted slogans that are a staple in the Indian mainland: Har har Modi, ghar ghar Modi. On Hussain’s lawn, Madhav said that BJP was hoping to form the government along with those who endorse peace. “We want the dynastic families who ruled Kashmir for so long to be out and make way for peace-loving politicians who do not endorse terrorism,” he said.

On the side, a hassled Hussain, shouted at people in Kashmiri to come closer. A few men sat on the grass under a tree. “Have you come here to sit in the shade?” Hussain shouted at them. They got up reluctantly and stood like others in the front. Madhav had to leave for Jammu, but before that he was taken inside to meet Hussain’s mother. He left shortly afterwards, as BJP slogans reverberated through the air.

Afterwards, people gathered around the table where two bowls containing cashews and almonds had been kept. In five minutes both bowls were empty. A little distance away, two paramilitary soldiers watched this spectacle. Then one turned to the other and muttered: “Kaju badaam yahin log khaayenge. Humare liye sirf goli hai. (The cashews and almonds are for these people only. For us there are only bullets.)”

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai

Love and Longing Nandini Nair

An assault in Parliament Rajeev Deshpande