Honey Laundering

The arrest of a couple of corporate executives exposes a global racket, with Chinese honey being shipped to America under ‘Indian’ labels to sneak past a tariff barrier

Sabrina Buckwalter

Sabrina Buckwalter

Sabrina Buckwalter

|

03 Dec, 2012

Sabrina Buckwalter

|

03 Dec, 2012

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/honey-laund1.jpg)

The arrest of a couple of corporate executives exposes a global racket

Stefanie Giesselbach, A young and pretty German executive in Chicago, US, had never been in any trouble with the law. She was smart and hardworking, and at age 28, had been promoted to national sales manager, with her company’s sales of honey in the US entirely under her charge. A rising star at Alfred L Wolff, a global food conglomerate, she had been posted to Chicago in 2006 after seven years at the company’s Hamburg headquarters in Germany. Although the trans-Atlantic shift entailed leaving behind family, friends and her boyfriend, it was also a move up the corporate hierarchy.

Sixteen months later, on a cold Monday in March 2008, Giesselbach’s career crashed. At O’Hare International airport, on her way to Germany to visit her boyfriend, she was arrested for fraud by agents of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Soon after, Magnus von Buddenbrock, a general manager at ALW who had dropped his colleague off at the airport, was stopped and arrested by ICE agents, too.

Investigators would later allege that Giesselbach and von Buddenbrock were at the centre of a multimillion dollar scheme to import cheap Chinese honey and disguise its real origin to evade US tariffs. China is the world’s top producer of honey: it turns out about a quarter of the world’s supply.

Chinese honey is cheap and the US had been a major importer. But in 2001, in the wake of a US government investigation that found domestic honey producers being harmed by significant price disparities between Chinese and American honey, the US levied an anti-dumping duty of roughly $1.20 per pound (454 gm) on Chinese honey. This tariff, its imposition implying that this honey was being sold below its real cost of production, was intended to level the playing field for American beekeepers who could not compete with imported honey selling in America at half their cost.

For companies like ALW that were importing tonnes of Chinese honey into the US every year, this was a big business setback. To evade the duty, some of them started getting shipments via third countries, with the honey’s point-of-origin relabelled accordingly. After all, no tariff was due on honey from India, Malaysia, Mongolia or Russia.

The operation soon came to be called ‘honey laundering’. ALW was one among several firms doing it, but it has been in the spotlight ever since the arrests. According to a 44-count indictment of the firm, over 2004-06, it laundered over 2 million pounds—900 tonnes—of Chinese honey through India, evading nearly $80 million in duties.

THE ORIGIN OF HONEY FRAUD

Honey laundering is a complex exercise that involves several players in the honey chain from apiary to wholesaler to retailer. In the case against ALW, evidence was presented to show the use of fake country-of-origin documents for shipments, replacement of labels on Chinese containers with fraudulent ones, switching of honey containers in a third country, and even the blending of Chinese honey with glucose syrup or honey from another country.

In plea agreements submitted separately in Chicago to the federal district court of Northern Illinois in March and April 2012, Giesselbach and Von Buddenbrock admitted to conspiring with other ALW executives and Chinese traders to ship Chinese honey to the US in the guise of Indian, Malaysian, Mongolian or Russian honey. Von Buddenbrock admitted that in the eight months between September 2007 and May 2008, he helped facilitate 11 purchase orders of fraudulently labelled Chinese honey in order to avoid some $3.2 million in duties. As part of her plea agreement, Giesselbach admitted to helping ALW avoid over $17 million in duties on over 100 orders for Chinese honey she placed from December 2006 to May 2008.

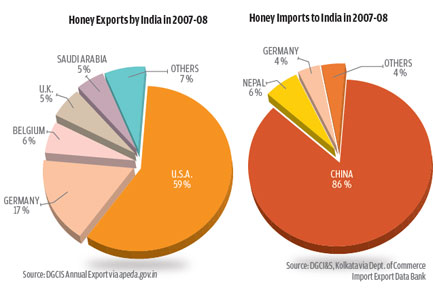

Trade data suggest that such practices were quite common. In 2002, the year after the duty was imposed, Chinese honey imports to the US dropped more than 40 per cent. Indian honey imports, on the other hand, zoomed up dramatically that year from nearly nothing to several thousand tonnes, according to US Census Bureau figures, and then kept soaring year after year (see chart ‘US Honey Imports’). Large quantities of honey were also shipped in from Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam and Malaysia, even as official Chinese imports staged a revival for a few years and then crashed. In 2011, imports of honey from India, at about 26,000 tonnes—up 4,000 per cent since 2001—were many times the figure from China.

The real origin of all this honey entering the US was bound to raise suspicion. In a 2011 Senate testimony, Richard Adee, past president of the American Honey Producers Association and current chairman of its Washington Legislative Committee, pointed out, “India just doesn’t have the capacity to produce nearly what they’re shipping. It’s pretty obvious when you look at the numbers.”

Over the period from 2007 to 2010, honey imports by the US from India more than doubled, while imports from Vietnam rose by 25 per cent. According to 2011 figures, Vietnam and India held the top second and third spots for honey exports to the US, with a combined total of about 54,000 tonnes.

However, the two countries together produced only about 51,250 tonnes of honey in 2010, according to figures of the Food and Agriculture Organization. Surely, they could not have ramped up their output so sharply within a year to export so much more to the US and still have kept their home markets supplied with no disruption. “When there’s this miraculous surge, it defies global trends. There was virtually no [extra] production of honey in India,” said Ron Phipps, a global honey expert.

GREAT INDIAN TREACLE TRICK

India’s Grand Trunk Road, which runs past Ludhiana in north India’s Punjab state, is a dusty stretch of highway that would be unremarkable were it not for all the honey stands and shops that line it. Along the road, one can spot just under a dozen different honey farms, shops or companies. Of these, one is hard to

miss—the sprawling headquarters of Little Bee Impex in Ludhiana. It is a shiny testament to India’s honey boom. A shimmering mirage on GT Road, its imposing structure rises amid a scattering of small bee farms with wooden sheds and hand-made equipment that dot the highway. As the top exporter of Indian honey, its stuff reaches far and wide.

It is a family-run business, and its Indian owners assert their innocence in the global honey laundering scam. Not all those who work for the company will vouch for that, though. In an interview, an employee who wishes to remain anonymous claims that his company gets Chinese honey and mixes it with Indian honey.

“They’re taking Chinese honey?”

“Yes.”

“How do you know?”

“I know, I am working in [the] laboratory, I just find how much glucose, how much sucrose…”

“How much Chinese honey do they take?”

“I think, 10-15 containers.”

“How much is one container?”

“That is 20,000 kg of honey… They take from China honey and mix it with Indian honey.”

Whether or not allegations that Little Bee Impex launders Chinese honey are true, the company’s honey has been placed on the US Food and Drug Administration’s ‘Import Alert’ list for having tested positive for unsafe levels of antibiotics. This means that any entity that receives honey from the company can reject it rightaway.

SG Agarwal, vice-president of quality assurance at Little Bee, insists that his company’s honey is safe: “We are not going to export even a single drop of honey which does not meet the requirements of the United States.” He goes on to explain that, “We are on that watch list because of a few baseless articles that got published in the media of the United States.” On being reminded that the list is drawn on the basis of scientific test results, he says, “They were not based on testing. I have asked them if they will provide me the source [of this information]. If they were writing about us, they should have contacted us. We were not contacted at all… they have not provided a single report.”

China used to export over 23,000 tonnes of honey to the US at the beginning of the millennium, a figure that crossed 30,000 tonnes in half a decade but has fallen drastically since. Over 2007 to 2009, Chinese honey exports to the US crashed, but India imported 2,164 tonnes of Chinese honey in 2007-08, which was more than four-fifths of all the honey that India imported, according to figures of India’s Department of Commerce. That year, of all the honey that India exported, almost 60 per cent went to the US, a proportion that has risen since.

There seems no end to India’s honey export boom. According to ship reports for 2010 and 2011 published in American Bee Journal, India shipped more honey in the first few months of 2011 than in all of 2010. Amit Dhanuka, CEO of Kejriwal Honey, one of the country’s bigger exporters of honey, says India could export many multiples more of honey every year. He acknowledges the problem of trans-shipment, but glosses over the issue. He attributes a surge in Indian honey production in recent years to the introduction of a new species of bee in the 1970s that produced far more than the domestic breed. That and the lure of the global market. According to him, the business of beekeeping boomed only after farmers discovered the vast export potential. “India did not consume a lot of honey,” he says, “It was consumed for more medicinal purposes than [as] food.” Once word of this great global opportunity went around, by his account, production went up exponentially.

Honey experts in the US are sceptical of that story. Phipps points out that India sent an especially large quantity of honey to the US last year, a period that coincided with US surveillance of ‘Malaysian’ and ‘Indonesian’ honey suspected of Chinese origin. “In Chinese beekeeping journals, they talk about ‘having’ to export [honey] through India and Thailand,” he adds.

However, Tarun Bajaj, general manager of the Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority, dismisses the involvement of Indian exporters in honey laundering. In an email response, he states that, ‘Chances of exports of Indian honey blended with Chinese honey to the US are negligible.’ He says that India’s Export Inspection Council inspects every honey consignment to ensure that a set of standards are met, a process that includes lab tests.

Giesselbach and Von Buddenbrock, though, have admitted in their guilt pleas that Chinese honey was being shipped to India, relabelled as Indian- origin honey, and then sent to the US.

THE FALL WOMAN

Giesselbach was 28 when she arrived in Chicago in November 2006 to replace Thomas Gerkmann, ALW’s national honey sales manager then. Von Buddenbrock, who arrived in Chicago five months later to replace Thomas Marten, was just 30 then. The two were initiated into honey fraud by company executives who were older and savvier than they were, but who were also leaving ALW’s Chicago office at a time when its operations were coming under scrutiny for the scam.

When she arrived at the ALW office on the 4th floor of a nondescript office building on Wabash Avenue in downtown Chicago, Giesselbach found herself in the midst of a cover-up. As she would later admit to investigators and the court, she participated in the exercise and carried on with the honey fraud. It was business as usual for ALW.

She had known about the fraud even before she arrived in Chicago. When she was arrested at O’Hare, ‘Giesselbach told the agents that she was aware that ALW had been transshipping Chinese honey since before she and Von Buddenbrock joined the company,’ according to the complaint filed against her in May 2008.

There was much more to the scandal than securing false certificates of origin. Giesselbach admitted in her guilty plea agreement that in May 2007, she requested a custom-house broker to refrain from listing ALW on any trade documents in order to avoid a paper trail. In the same document, she also admitted to routinely reviewing purchase orders, sales contracts, bills of lading (used for shipments), packing lists, country-of-origin certificates, laboratory reports, and delivery instructions to ensure that Chinese- origin honey was not described or listed as such in the relevant documents. It was this sanitised paperwork that ALW’s American clients were shown.

Court records also provide a glimpse of how the fraud was done in one transaction between ALW and an Indian trans- shipper. During the transaction, a conflict arose over whose responsibility it was to re-label the Chinese honey containers: of the Chinese supplier or the Indian trans-shipper? Emails obtained through a search warrant and presented in court indicate that ALW’s Chinese honey supplier, Kirkam Ltd, was supposed to have affixed new labels to mask any Chinese identifiers onto the containers, leaving the Indian trans-shipper the last task of mixing the Chinese honey with Indian honey once it arrived in India. Such mixing was a precaution designed to obscure the honey’s real origin.

Dated 12 February 2004, this email from the Indian transshipper to ALW executives in Hong Kong, Germany and Chicago states:

‘Please be noted that in this particular transaction we were only suppose to shift the Honey from 1 container to the other and just dispatch as it is to USA. All the markings on the drums were suppose to be done by Kirkam… It was very clearly stated before the agreement between Kirkam and us that our job was only to shift…’

Altogether, ALW was believed to have imported more than $40 million worth of Chinese honey from 2002 to 2009, while avoiding duties of almost $80 million. From the winter of 2006 to May 2008, a period during which Giesselbach and Von Buddenbrock ran ALW’s honey operations, the company falsely declared the country-of-origin of 85-90 per cent of all the honey the company imported, according Giesselbach’s plea agreement. Even earlier, in fact, from 2002 to 2006, all the honey that ALW said it imported from India was entirely Chinese, as her plea document reveals.

ALW closed its Chicago office in May 2008, right after Giesselbach’s arrest. All the assets of this subsidiary were transferred to a German company called Norevo GmbH, and all the remaining employees left the US. And then, on 14 June 2012, the charges against the two corporate entities were dropped. Randall Samborn, public information officer for the US Attorney’s office in Chicago, said the government had filed a motion to dismiss the charges against the defendant corporations as they had no US presence or were mere shells.

“It was as if they just left [Giesselbach and Von Buddenbrock] holding the bag,” says Jim Marcus, Giesselbach’s lawyer. “There’s no doubt she did it. I could never win a case for her, but the issue is how I can lessen the blow for her.”

About The Author

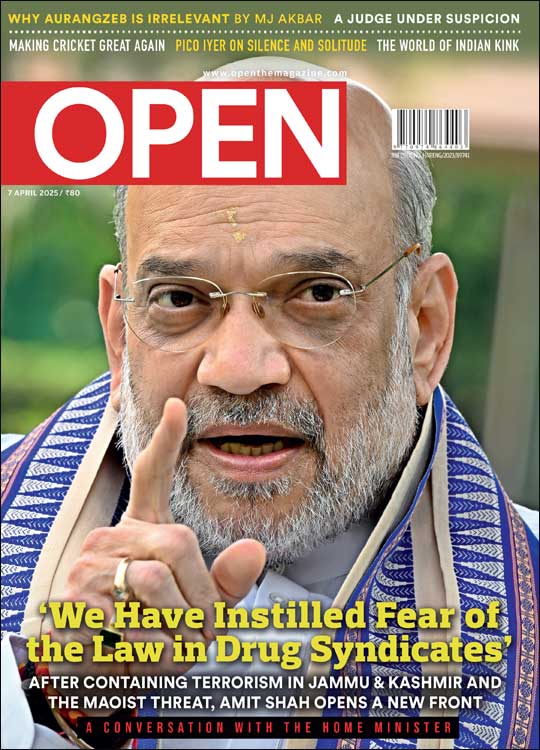

CURRENT ISSUE

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post