The Outcastes of a Liberated Zone

In Abhujmaad, the choice Maoists offer is stark: confinement or exile

Supriya Sharma

Supriya Sharma

Supriya Sharma

|

08 May, 2012

Supriya Sharma

|

08 May, 2012

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/outcasts1.jpg)

In Abhujmaad, the choice Maoists offer is stark: confinement or exile

An inky winter morning, a narrow mud path led past a creaking water handpump to a maze of homes and small fires. A short woman emerged from her house with a cooking vessel as I stepped forward to say ‘Namaste’.

“I am the patrakar (journalist) from Raipur,” I said in Hindi, “I had come here with Sitabai, remember?”

Despite the darkness, I could see a broad smile of recognition, as Damki Bai hurried to place the vessel on the ground and came forward to hold my hands, speaking in Gondi, with its high pitched notes and singsong lilt.

She led me a few steps away to a huddle of women around a fire, their frail bodies wrapped in coarse blankets as they rubbed their gnarled hands against the heat. “Raipur te Medam…” she said, by way of introduction, and gestured me to sit and join them, while she placed the metal vessel brimming with water on a mud oven and lit a fire below to cook the morning meal of rice.

It was cold here, colder than in the dense agglomeration of brick buildings in another part of Narayanpur, a town in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, 250 km away from Raipur, the state capital. This habitation was just a cluster of small mud homes spread across flat farmland on one side and a series of scrubs on the other that went on to gently rise into the hills. In the monsoon, when I first visited, a jade green carpet of paddy swayed in the haze as the brown earth and mud houses faded into the grey sky.

For all its rural idyll, this cluster was part of Narayanpur town. Its residents did not own the land, nor did they get any municipal services. They got no piped water or electricity. And like most squatter colonies, it had grown haphazardly, each plot a different size. And it continued to spread as families of Maadia tribals trickled in, leaving their traditional homes in the forest behind, as Damki Bai’s had done.

Maadias are members of one of 75 Adivasi or aboriginal communities classified by the Government as PTG—an acronym that initially stood for ‘primitive tribal group’, but was later modified to the more politically correct ‘particularly vulnerable tribal group’. In its 2009 annual report, India’s Ministry for Tribal Affairs describes PTGs as ‘tribal communities who have a declining or stagnant population, low level of literacy, pre-agricultural level of technology and are economically backward…[they] generally inhabit remote localities with poor infrastructure and administrative support’. Of all of Bastar’s tribal communities, this description fits Maadias the best.

The region of Bastar, with its 13,000 sq km of rugged topography spread across central India, including south Chhattisgarh, is bigger than many Indian states. Despite the steady arrival of outsiders, Adivasis still form the region’s majority, making it the country’s last big tribal homeland. Of this, 3,900 sq km—bigger than the state of Goa—is part of a thickly forested plateau called Abhujmaad. ‘Abhuj’ means the unknown, ‘Maad’ means hill.

The people of Maad, or Maadias, were quite reclusive until recently, maintaining little contact with the outside world. That changed a few decades ago, as traders began making forays into Maad to sell their wares, and then Maadias began flocking to the nearest town, Narayan- pur, to shop at weekly markets. Over the past decade, entire families started abandoning their homes in Maad to move to Narayanpur and settle for a town life.

This was no simple urbanisation impulse, according to a local journalist. The exodus, he claimed, was a desperate attempt by Adivasis to escape violence in Maad. “Someone in their family had either been killed or beaten up by Maoists,” he said, “or they simply anticipated trouble and ran away.” By a quirk of naming, the settlement of these refugees in Narayanpur came to be called Shanti Nagar, or ‘peace town’.

That morning in Shanti Nagar, as the fire crackled on the ground and light broke in the sky, the women and I struggled to hold a conversation. They understood little Hindi, spoke even less. I told them I had just returned from Maad, and had been to some of their villages, the ones they had left behind. Then, to explain what I was saying, I pulled out my camera and began scrolling images taken on my trip.

“Oh, Kokameta… iskool,” said a woman, instantly recognising a rundown school building in Kokameta village. They bent forward excitedly and began to comment on what they saw—the ashram (centre run by Hindu monks), the ghotul (traditional centre for community and youth life), and, amid peals of laughter, the bajaa (a large musical drum).

As the photo scroll came to rest at a pyramid-like red structure, their voices dipped, and one of them said, “Muth”, while another said “Irakbatti”; a ‘muth’ is a memorial built by Maoists in honour of a slain leader, while Irakbatti was the village where it stood.

When I first spotted the towering memorial in a clearing just outside the village, it left me awe-struck—it was the grandest Maoist monument I had seen. Painted bright red, with gleaming steel bars around its base, the pyramid-like stack of rectangular blocks towered as high as a two-storey building. Who was this leader who’d inspired such architectural grandeur? I stepped closer to look for a name inscription. Oddly, there was none.

The mystery ended in Shanti Nagar. The women knew who it was. “Jaggu ka muth,” they murmured.

“What, say again?” I asked.

“Jaggu, Jaggu dada.”

A woman said something in Gondi that I could not understand. All I caught was the Hindi word ‘achcha’ (good).

“He was a good dada?” I asked, “Jaggu was good?”

She shook her head, “No”, and repeated herself. It took many repetitions, and help from others who loosely reconstructed her sentence in Hindi, to understand what she had emphatically said: “It is good that he is dead.”

‘Dada’ means elder brother in many Indian languages. Much like the relationship, it has emotional shades ranging from respect and affection to fear and domination. In the jungles of Bastar, it is hard to say which shade of meaning is at work when an Adivasi uses the term ‘dada’ or ‘dadalog’ for Maoists.

It was in June 1980 that the first Maoist squad came to Bastar, writes journalist Rahul Pandita in his book, Hello Bastar. The squad was made up of young, university-educated revolutionaries from Telengana, a backward region in the state of Andhra Pradesh. Crackdowns in their home state had made their leader Kondapalli Seetharamiah propose the idea of a ‘rear base’, a sanctuary to recoup.

North of Telengana lay an expanse of forest inhabited by several tribes. Called Dandakaranya, it overlapped roughly with a vast part of Bastar, with adjoining forests in neighbouring states. Here, the Indian State had chosen as its representatives not teachers and doctors but forest guards who protected the forests not from illegal timber businesses but firewood-collecting Adivasis. Another set of exploiters were traders from the plains who made the most of forest dwellers’ naivete, cheating them of the fair value of their forest produce.

These traders came from far and wide, often escaping their own set of miseries. Most were from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Bengal, where small landholdings were no longer enough to feed large families. Some left on their own, others were forced out—like a shopkeeper I met in Narayanpur whose search for dry land, after a flood drowned his village in Murshidabad, Bengal, took him 1,000 km away to Bastar in the mid-1980s. He sold fish on the main highway before someone suggested he explore Maad, which had no shops but many Adivasi would-be shoppers. And so, one day, he piled sacks of salt, soap and potatoes on a cycle, and joined a small group of men riding through the jungle to the village of Kokameta. “Maadias would see us and flee,” he recalled. “Bahut bhole thhe (they were simple folk).” This worked well for him. He could sell Rs 5 worth potatoes for Rs 10. Business was great, until the Maadia children picked up arithmetic, the dadalog began keeping an eye on traders, and the risks started outweighing the returns.

The flood-fleeing trader’s Maad trips came to an end after he ran into a Maoist squad a few years ago. “It was Diwali. I had gone with a friend to buy a goat. We were returning when we were flagged down by dadalog,” he said. “‘Where are you from?’ ‘What are you doing there?’ ‘Who did you buy the goat from?’ ‘How much did you pay?’ Their questions were endless. Thankfully, we had paid for the goat. They noted our answers and let us go,” he said, “But I was rattled. One small mistake in Maad [I realised] could get you killed.”

By acting as gatekeepers and watching out for Maadias, Maoists earned their gratitude and support. And, more crucially, space—not just for a ‘rear base’, but for a state of their own. To set one up, they had a network of political workers, a women’s organisation, a cultural group, and even a publicity wing with a printing press, all guarded by a guerilla army of Adivasi boys and girls.

By the mid-90s, Abhujmaad, the unknown land, had been recast as ‘a liberated zone’ by Maoists.

If you look for Abhujmaad on the map of Chhattisgarh, you won’t find it. It lies subsumed in the administrative block of Orchcha in Narayanpur district, an irregular rectangle, longer length-wise, with the town of Narayanpur at its top right corner. Radiating southwards from the town is a highway, along which are strung security camps. The highway acts as a frontier, beyond which lies Maad, a 3,900 sq km expanse of land without a single police post.

Narayanpur, an unremarkable town located uneasily on the periphery of a parallel state, tries hard to maintain the veneer of governance by Chhattisgarh state with its profusion of decrepit government buildings that house district officials who must find ways of spending crores of development money meant for Abhujmaad without going there. In 2011, they managed to spend just a third of the Rs 25 crore sent as central aid under the Integrated Action Plan, and it was spent, among other things, on raising the height of boundary walls of buildings in the town. Apart from a few government schools, government money spent in Abhujmaad is routed through the Ramakrishna Mission, a Hindu organisation that runs schools, clinics and crèches in Maad.

Headquartered in Bengal, the Mission came to Narayanpur in 1987 and became the only organisation other than that of Maoists to have an active presence in Abhujmaad. Since then, another institution that has made tentative forays in Maad is Shilpa Gram, a crafts centre run on government grants. In the early 90s, it sent trainers to Maad. Among them was a craftsman called Santosh Pal, a short moustachioed man from Tripura in the Northeast, where tribal people had graduated from making bamboo baskets and trays for their own use to pen stands, magazine holders, chairs and tables for sale in town fairs. Pal was hired in 1991 to teach Maadias the craft. He remembers travelling to their villages and staying there, often for months together, without any trouble. “It was okay to go to Abhujmaad as long as you did not mess around,” he said. “The Maoists were a quiet, peripheral presence. There was not much violence then.”

There is no clear-cut mark for when it changed, but change it did. It happened gradually over the past decade, according to everyone at the crafts centre. The violence increased, they observed, and Maoists became less tolerant. No trainer was killed, but there was an air of fear that stopped their visits to Maad. “So we have begun to run the same training programmes here, which makes sense, since there are so many Maadia women who now live in Shanti Nagar,” said BK Sahu, the centre’s manager, an affable middle-aged man. “They are destitute and could do with some help.”

It was here that I first met Sitabai, who lived in Shanti Nagar, and came everyday to the centre for work. Dressed in a traditional red cotton sari, laden with clunky silver jewellery, she came and presented me a bunch of hibiscus flowers as I sipped tea in Sahu’s office. She looked about fifty, or maybe older, had a slight squint and smiled a lot. But as she left, Sahu, who had a melodramatic style, told me, “There is sorrow behind her smile. She has a very sad story. Naxals killed her son and her husband died of an illness, bechaari.”

Sitabai was born to a Maadia family, but had an unusual childhood. Her mother was employed as a domestic worker at a trader’s house in Narayanpur. So, as a child, she picked up Hindi as well as town habits—so much so that when she returned to Abhujmaad as a young bride, she had trouble accepting the ways of her tribe. “The women went around uncovered, no blouses, not even a cloth,” she told me, saucer eyed.

Eventually, she did settle down to life in Gumiyabeda, her husband’s village, a day’s walk from Narayanpur. They had four children—two girls and two boys. The girls were raised at home and the boys were sent to Narayanpur to study at the Ramakrishna Mission school. But much to Sitabai’s disappointment, the elder one failed his class ten exams and returned home. “I said, ‘Don’t leave school, try again, or take up a job in town.’ But he said, ‘Ma, I have studied enough, I want to do farming.’ So what could I do? I married him off and he had a child.” The young man kept visiting Narayanpur, though. He told her he was training at the mission’s agricultural institute. This was not unusual—old students often came back to the mission for vocational courses.

One day, Sitabai and her family had gone for a relative’s funeral in another village. She decided to stay back there, as did her husband, while their elder son said he would return to their village.

“When was this,” I asked her.

“Thursday,” she said.

“No, which year, how many years ago.”

She thought hard. “Four. No, seven. Maybe six.” Like most Adivasis, time for her did not neatly fit into years. Not that it mattered—the memory was etched in her head, sharp as ever.

“Friday, I got back home, but he was not there. I was told they had taken him away. I walked and walked looking for him, crossed the river, but could not find him,” she said, eyes glued to the ceiling, voice choked. Her cousin came to say he had been found near Brehibeda on the outskirts of Narayanpur. Distraught, Sitabai walked towards this town. It had been three days of searching, of “bhookh aur bukhaar (fever and hunger)”, and she was in tears.

At a checkpost a few kilometres short of Brehibeda, the police stopped her. They asked her why she was crying. “Mere bete ko idhaar kahin ghatna kiye hai.” They have done my son in somewhere here, she told them. The police knew. Not too far away, a blood splattered body was being loaded onto a truck.

“They had slit his throat,” said Sitabai with a hand gesture, “and there was a bullet in his back.”

After a long pause, I asked her why they had killed him. (Later, it struck me neither she nor I ever named the killers as Naxals, it was always “they”.)

“Someone in the village had done chugli.” Someone had told a tale, a false one.

“What sort of chugli?”

“Some said that he was joining the police, that he had gone to fill a form in Narayanpur. But the form was not for the police, it was for a chaprasi naukri (peon’s job). They even said my son was a mukhbir’.” An informer—that is, someone betraying the revolution and thus deserving of death in the unambiguous Maoist book. Mukhbiri, or the crime of leaking information, was arguably the most commonly cited reason in Maoist statements on civilian killings.

I had come across one such statement in Narayanpur earlier last year. Its finely printed Hindi had a bold headline: ‘Shikshakarmi ke naam pe kalank, Kamlu Varda kee maut’ (Disgrace in the name of education Kamlu Varda’s death). A school teacher, Kamlu Varda, had been executed, it said, since he had been regularly supplying information to his uncle who worked in the police. He was killed, the note added, after being tried in a jan adalat, or people’s court, the Maoist version of direct democracy where villagers gathered and presumably passed verdicts on wrong-doers.

Some time after her son died, Sitabai found herself in a jan adalat too. How many people were there, I asked her. Again, she had trouble with the number. People from many villages, she said—which could mean hundreds. But why was she taken there? “My daughter-in-law went away to remarry and left my grandchild, who was still crawling. The child fell ill and my husband and I went to Narayanpur to get him treated. We stayed there for a month-and-a-half. When we returned, there were whispers in the village that [Naxals] were upset. One day, they showed up, tied up my husband and began taking him away. I ran after them. I said, ‘You killed my son, and now you will kill my husband’.”

At the jan adalat, a Maoist commander stated their crime: they were visiting Narayanpur too often, despite being told not to. They were defying orders. “He asked the villagers, ‘Maare ya chhode?’ (kill or leave them?). There was silence. The villagers kept quiet. He kept repeating, ‘Maare ya chhode?’ People said nothing. Eventually, they let us go.”

That night, Sitabai decided to leave. She wrapped her jewellery in a small bundle, her sleeping grandchild in a bigger one, and trekked to Narayanpur, this time never to go back.

Less than 200 sq ft of space was enclosed within its mud walls and under its sloping tiled roof. The hut opened into a small frontyard fenced with dried branches. On its bare walls hung pictures. One was of a young man in black-and-white, her son, the one killed for alleged mukhbiri. There were other pictures too. Sitabai, dressed in finery, posing with men in suits and safaris. “That’s Raman Singh,” she said, pointing to her picture with the Chief Minister of Chhattisgarh. Her felicity with Hindi had made her a natural choice to receive visitors at Shilpa Gram (she would wear clunky jewellery and a red cotton sari, though, to look authentically Maadia). Her language skills came to my aid in conversations with others in Shanti Nagar. And yet, most of them—even those who did not use the language—described themselves with the Hindi phrase ‘Naxal peedit’ (Naxal victimised).

On their part, Maoists had other views on Shanti Nagar and its residents. Gudsa Usendi, spokesperson of their Dandaka- ranya Zonal Committee, was impatient when I questioned him over the phone about the stories I had heard in Shanti Nagar. “Do you know the real name of Shanti Nagar?” he asked. “It is Mukhbir Mohalla. Sadly, we have to act against those who collaborate with the enemy, who jeopardise the interests of their own people. And all decisions are taken democratically in jan adalats.”

For Maoists, Shanti Nagar was a colony of betrayers but its residents insisted on being called ‘victims’ of the movement. Over time, I saw how both could be true.

Budhiyaari had an easy smile, and better still, spoke a smattering of Hindi. Before coming to Shanti Nagar, she lived with her husband and children in Maad in Irakbatti village. All was well until the police picked him up one day.

“The police tied my aadmi (man) and took away him away. They said, ‘Show us Naxalites.’ Out of fear, he took them to the village. But he felt if he stayed back, Naxalites would kill him, so he returned [to Narayanpur] with the police.”

“But why did the police pick him?”

“They said he was with the Naxals.”

“What did they ask him to show?”

“Saaman.” Things.

“What things?”

“The people of the village had made a house for Naxals, jhhopdi type ka (like a hut). Naxalites used to hold their meetings there. Once the police beat him up, he had to show it.”

The story was terrifying—the police had forced her husband to reveal guerilla hideouts, exposing him to Maoist ire—but its protagonist was not around to fill the details. He had gone to earn his family’s rozi roti (daily bread). In the village, Budhiyaari’s husband would cultivate crops on his own land, but in Narayanpur, he worked for others, waiting at street corners every morning to be picked up by contractors.

As it got dark, the three of us—Sitabai, Budhiyaari and I—drifted to a neighbour’s house. It was a small room filled with a sense of foreboding. Maybe it was the low light and long shadows. A girl in a blue school pinafore crouched in a corner. A woman hunched in another corner, blowing air into a mud oven. It was time to cook the evening meal. Vegetables had been cut and a pan of rice lay nearby.

“The Naxals killed her husband, just like they killed my son,” said Sitabai as she stepped forward to make introductions. The woman was Damki Bai. She seemed older than Budhiyaari and younger than Sitabai, which meant she was possibly in her forties. Why did the Naxals kill her husband? “Because her husband,” Sitabai answered, pointing to Damki first, and then to Budhiyaari, “and her husband, they were both tied up and taken away by the police.”

It turned out the families were related, although they lived in different villages. One festival day, Budhiyaari’s husband was visiting Damki’s family for a feast, nawaa khaane, when the police abruptly showed up and detained both the men, dragging them off to Narayanpur. Anguished, Damki rushed to Narayanpur looking for her husband, Kohla Ram. She even paid a bribe of Rs 2,000 to a policeman—needlessly, since the police were going to release her husband anyway after they had extracted the information they sought. Kohla Ram returned to the village only to be killed by Naxals.

“I fell at their feet,” said Damki in Gondi, with Sitabai translating it into Hindi. “I said, ‘Do not kill him, I will give you whatever you ask.’ But they still killed him.”

“In front of her own eyes?” I instinctively turned to Sitabai. But Damki Bai did not need a translation. She understood the question and stretched her arm across her shoulder to point at her back and then pulled it forward to make a quick slashing move across her throat. The gesture, again, needed no translation, but Sitabai offered one all the same. “Bandook se mare,” she said in a lowered voice,“galaa kaat diya.” They had killed him with a gun and then slit his throat.

After burying her husband all by herself—no one in the village came forward to help, not even her relatives—Damki gathered her children and a few belongings and ploughed her way to the bigger village of Kokameta. It is difficult to imagine how—two of her daughters are disabled, their limbs claimed by leprosy. At Kokameta, it was bazaar day, traders from town had brought in tractors loaded with wares; in the evening, as they returned, the family hitched a ride with them to Narayanpur. The very next morning, Damki Bai went looking for work—at construction sites, or odd jobs washing, cleaning or sewing. She worked from 8 am to 6 pm everyday, renting a home at first and then taking a loan to build her present house. “She has a father-in-law in the village but he does not help. I have a brother-in-law who doesn’t help,” said Sitabai. “My brother-in law has five kids. None of them comes here. They think of us as enemies. They don’t even talk to us.”

I turned to look at the girl crouching in the corner, a girl Damki Bai called a ‘kodi’ (leper). “The other kodi is asleep,” she said. Did she have just two children, I asked. “No, more. The others are not here. They study in ashrams. Six are alive, two boys, four girls. And four others died.” Ten kids, I counted and exclaimed. Inadvertent humour—for the first time, everyone in the room laughed. Including a man who had entered unnoticed while I was talking to Damki. He turned out to be Budhiyaari’s husband, a middle-aged man named Budhram.

“Why did the police pick you up?”

“They said ‘You work for Naxals’.”

“How many days did they detain you?”

“Two weeks.”

“Did they beat you up?’

“Yes. They interrogated me. They said, ‘Take us to your village. Kahaan kahaan dera dalte hai tumhare gaon mein, thikaana dikhaana’ (Show us where [Naxals] stay in your village, show us their hideouts). They had beaten me up. I was scared, so I took them.” After the tour was over, the policemen brought him back to Narayanpur.

“The [policemen] said, ‘It is your wish. Go back if you want to, but soch lo (think it over).’ I said, ‘Sahab, you took me to Maad with you, the villagers must have seen me, the Naxals would have been told.’ Sahab said, ‘Okay, if you don’t want to go, then stay here’.”

“Her husband was with you?”

“The police warned him too, said, ‘Think it over, soch lo, you will be killed’, but he still went back.”

So the police had not just tortured two men into squealing on Naxals and exposing themselves to danger, they did so knowing its implications only too well. This was how the police operated in large parts of Chhattisgarh wracked by insurgency, detaining and torturing hapless locals with impunity. In each case, the police argued they had acted on credible information—that they targeted only those who worked for Maoist insurgents. Even if you ignored the fact that nothing could justify torture, if the men were actual Maoist supporters, why would Budhram have feared going back or Kohla Ram have got killed?

A conflict zone does not permit candour, and people who support outlawed groups are not known to confide in journalists. But though Budhram’s story had no hint of any support to Maoists, I still had to ask him this question pointedly: “Did you ever join or work for them?”

“Not me,” came his swift answer. “But my brother did. Instead of him, the police caught me. ‘Your brother is a Naxal,’ [they said], ‘you surely must know something. He must be telling you things out of brotherly respect, bade bhaiya bol ke.’”

Now the motivations of the police became clear. But I was curious about his brother’s motivation. What had led him to join the Maoist movement? “Uski marzi (his own wish).We told him not to. We said ‘This is not good work’,” said Budhram. The only one of four brothers to get a school education, he was 18-19 years old when he left to become a guerilla. “He was ninth pass, tenth fail. After studying so much, we told him kuchh toh milega, you will get something.” So why did he join them? I pressed on.

“How can I say? Main kaise bataoon, madam,” said Budhram, a note of irritation creeping into his voice. “All three of us told him not to.”

“Do you get to meet him?”

“No, he is dead. The police killed him. During elections. Police must have gone, there must have been an incident…”

“When was this?”

“Last elections.”

Unprompted, he continued, perhaps sensing a need to elaborate: “People join out of their own will. [Naxals] don’t grab your hand and take you away. Zabardasti nahin. No compulsion. Ek doosre ko dekh kar jaate hai. People join on seeing other people join.” Getting up to leave, he said, “Aaram se baithe baithe khaana hai. You get free food without working too hard.”

Muri’s story seemed a lot like Sitabai’s—except her son had survived. He was the eldest of three brothers, one who Maoists alleged was angling for a police job in Narayanpur. The son protested that he had simply filled a form for a peon’s job. They held him captive for a week without food or water. On the eighth day, they decided to let him go, with the diktat that the family must leave Maad for good. They were given no time. “‘Leave now, nahin toh khatam kar denge (you will be killed),’ they said. We left all the cows and oxen behind,” Muri recounted, her gaunt face, highlighted by a string of tattooed dots, expressionless.

How did she rebuild her life here, I asked. “The oldest son got the peon’s job he had applied for,” she said. “And the younger one became a mukhbir.” Was he the one who Maoists had accused of joining the police? “No, they had accused the older one,” she reminded me. “The younger one became a mukhbir only after we came here. He had to do something to live. And Rs 1,500 a month was not bad.”

Being an informer was not the only crime in Maad people had to pay for, it seemed. Defiance and dissidence were equally punishable. In September 2007, Mangal Ram, a young handsome man in Kokameta village, found himself resenting a dadalog decision to divide his family land, giving his cousins (five brothers) 100 acres, and his family (three brothers) 60 acres. “It was not fair, it should have been an equal division,” he told me. But Maoist arbitrators had divided the land equally: 20 acres for each man. “No, it should have been equal between families,” he insisted. The point is not who was right or wrong, but what followed when he voiced his dissent. He was taken captive and held for days before he managed to escape to Narayanpur.

“What do you do here?” I asked Mangal, as he hauled a bag of cement, his muscles rippling with the effort, across a distance. He smiled, looked around furtively, and said, “I work for the police.”

Had I finally found a mukhbir, in flesh and blood, willing to talk?

“No, I am not an informer,” he laughed, “I am an SPO.”

Special police officer, or SPO, was a controversial kind of police officer created by the Chhattisgarh government to enrol Adivasis into anti-Maoist police operations at one-fourth the salary of a constable. In 2011, the Supreme Court struck this scheme down as unconstitutional, berating the state government for unleashing more violence, using barely educated Adivasis as cheap ‘cannon fodder’.

When I met Mangal, he was, like the other SPOs, beset with job uncertainty. He was still getting a salary, but had no duties. Call it cockiness or courage, Mangal decided it was time to take a loan and build a home—one with cement and bricks—grander than that of others. Luckily for him, his job uncertainty did not last long. Within weeks, the government had come up with yet another idea, this time of an auxiliary police force with the same terms at higher pay scales, so that Mangal Ram and other Adivasi SPOs could go back to fighting Maoists.

The vast majority of Shanti Nagar’s residents, however, had no desire to fight anyone, not even government officials, for things like ration cards. When they left Maad, they had left behind the small pieces of paper that got them their scraps of welfare handouts from the State—subsidised food, sugar and oil. Those who tried getting new ration cards were told they could use them to draw their entitlements only from their village shops. “Who would go back for free rice if one could get killed?” Budhram summed up the absurdity.

They did not wait to be helped, they helped themselves, by picking up shovels, pickaxes and sundry instruments, as they went out every morning on foot or bicycle to look for work. Those who had their own farms in Maad did farm labour for others. Some used old connections: before she found a job at the crafts centre, Sitabai went to the family that had employed her mother. They took her in as a domestic help. For a while, Damki Bai did odd jobs, but then she got lucky and was hired with a dozen other women by the Ramakrishna Mission to work on vegetable farms. They paid Rs 100 a day, gave the women an evening snack, and better still, sent a tractor to Shanti Nagar to pick them up and drop them.

For an informer’s colony, Shanti Nagar had a strange demographic profile. There were more women than men, more older women than younger women.

The younger ones who lost husbands remarried. The older ones had no such hope or desire.

For the weakest and oldest, the last refuge was the crafts centre, where they sat under a shed, chipping away at bamboo for a stipend of Rs 450 a month. Mangti Bai, old, shrunken, waif like, smiled each time I walked past, and cried the only time I stopped to ask what had brought her here. “Beta maara (son killed),” she said, her voice cracking. “Mukhbir bol ke (labelled a mukhbir).”

“They are of no use to us,” responded Mayank Srivastava, the police superintendent of Narayanpur, when I asked him how many informers he had managed to hire among the people of Shanti Nagar. “They no longer live in Maad. They can no longer visit Maad. What information do you think they can provide?”

Maybe information on Maoists who visited Narayanpur for Sunday shopping, I hazarded. After all, Maoists were not Martians. They may live on little, but even little has to be bought somewhere. By posting undercover men in Narayanpur’s weekly market, the police could squeeze Maoist lines of supply. It was hard to say if they had done that, but it was evident that like every other measure of policing, it had criminalised ordinary Adivasis. There was a pronounced gender imbalance among the shoppers who poured into town every Sunday. Women far outnumbered men. The men stayed at home in fear that if they went to town, they could be held back by the police for questioning.

Whatever help the people of Shanti Nagar provided the police, it had not earned them water or electricity, let alone legal ownership of land. (That some had been ingenious enough to loop a wire to overhead cables and drag it to their homes was a testimony to their growing urban skills.) The district administration had allowed the colony to emerge but had not bothered to acknowledge its existence. When I asked the district collector about the status of the colony, he said it was “technically illegal” but the government was “thinking about it”.

For a government that lost no opportunity to recount the number of lives lost to Maoist violence, and was quick to claim sympathy for victims, it had disbursed just Rs 24 lakh over three years as ex-gratia and relief to 40-odd families (not even a fraction of the families that lived in Shanti Nagar) in Narayanpur. None of the people I met featured on the list. “Not everybody who claims to be a victim is a victim,” scoffed the government official who handed me that list, implying that people were exaggerating their troubles. Oddly, Maoists would’ve agreed.

Cold air streamed past as our motorcycle twisted on a rollercoaster-like dirt track. I was finally in Abhujmaad. It had taken months to find a guide willing to take me here. In Narayanpur, everyone had warned me that the area was off-limits. “Is that so?” I had asked Gudsa Usendi on the phone. “You can visit, you won’t be stopped,” he had said. But it was not as if I was carrying a letter to that

effect from him. And it had been a while since we had spoken. So I had decided to stick to a route that had Ramakrishna Mission centres. This gave me an alibi. If stopped, I could say I was visiting these centres.

My guide was a talkative man, silenced only by the effort of navigating the bike in such tough terrain. Every now and then, a steep incline would force us off the bike, making us trudge upwards in a cloud of dust. Or a shallow river would make us wade across. The extended ripples of soft sand on either side of these river crossings showed how far and high the waters spread in the monsoon—enough to isolate Maad for weeks and months together, as my guide said.

Budhram and Budhiyaari had lived in Irakbatti before he was picked up by the police and could not return in fear of Maoists. Might the rest of their family still be around? I looked for the house of the village sarpanch, since a headman was usually the best source of information on such matters. But the sarpanch was not at home. His shy wife, plastering the floor of the house with cow dung, looked up to say he had gone on a hunt. Would she know about Budhram, I asked her. She looked surprised and pointed in the direction of a hut. A frail man, too old to hear or speak, sat outside the hut. A young child stepped out. “Is this Budhram’s house?” I asked her. “He is my uncle,” she said. Were her parents home? No, they were not. What about her other uncle? “He has been taken away by the police,” she said. Budhram, you mean, I said. “No, another uncle.” Perhaps, he was the brother who had joined the Maoist insurgency and been killed by the police. But the child was too young to be burdened with questions of violence.

The sarpanch’s wife said little when I went back to talk to her. Why were people leaving the village? She had no answer. Did anyone trouble them—the police or dadalog? “The police do not come this far inside [the forest], but when the men go out, [the police] often keep them from coming back here,” she said.

As the day progressed, I began to despair. Afternoons were the worst time to land in a village. Most people were out at work. And my guide was getting restless. Unless we left soon, he warned me, we would not make it to Narayanpur before dark. There was no hope of going to Damki Bai’s village. It was much too far. Instead, we could stop at Kokameta, which would lie on our way.

Kokameta was the largest village in this part of Maad. Dilapidated government buildings were scattered sepulchrally around a vacant ground—schools that had children but few teachers. I approached a woman and reeled off a series of names of people I had met in Shanti Nagar.

Mangal Ram’s name—the young man who had escaped Maoist custody and turned into an SPO—struck a bell. “His sister is right there,” the woman said, pointing at a girl in a yellow shirt walking slowly in the distance, balancing a water vessel. I ran after her, and caught up as she turned into the yard of a hut. “I have come from Narayanpur. I have met your brother Mangal Ram,” I blurted out.

She returned a blank look. For a moment, I thought maybe it was a case of mistaken identity. “Mangal Ram, the one who was forced to leave the village…” my voice trailed off. An old woman looked out of the hut. I turned to her, repeating my questions. “Is this Mangal Ram’s house or not?” I asked feebly. Both mother and daughter ignored me. Confused, I wondered if it were best to leave. “I am sorry if I disturbed you. It is just that I met Mangal Ram in Narayanpur and wondered if his family was okay,” I said, as I got up to leave. The old woman looked up, moved closer, and said, “My son made no mistake. He was falsely tricked by his cousins and now all of them would rather have all of us leave so that they can take away our land.” She continued, “Dadalog would come and tell me, ‘Your son has joined the police, so you’d better leave the village too.’ But I told them I would rather die here than go away.” This sudden outburst left me speechless. Did she want me to take a message for her son? “No,” she nodded, and went back to work.

The sun was descending as I walked around Kokameta, trying to speak to anyone who cared to speak to an outsider. Many huts lay locked but had signs of occupancy—a charpoy outside, or a tray. But a few looked forlorn. “Two families left this week,” said an old man. Why? “Galti kiya hoga (must have made a mistake).” What sort of mistake? “They must have gone to Narayanpur without informing dadalog.” It was evidently a Maoist rule: you could go freely to Narayanpur for a day trip, but if you planned to stay overnight, you needed their prior approval.

The need of Maoists to safeguard Abhujmaad had left its people, local Maadias, with a hard choice: either be prisoners of the liberated zone or its outcastes, like those who lived in Shanti Nagar.

What about the police, did they come and trouble people here? “They came here last year and there was an encounter. They forced the villagers to tie and carry the bodies on sticks,” the old man said. (In March this year, the security forces reportedly went deeper inside Maad in pursuit of Maoists and, according to some reports, allegedly burnt homes and killed villagers along the way. The police deny the allegations.)

As light faded, my guide started getting edgy. “We’d better get going,” he insisted. We left Kokameta to a gaggle of children waving at us, the offspring of shy Maadias who would once run away at the hint of an outsider. Ahead, we heard that a Maoist squad was in the area, just around the river bend. I wondered if we would run into them. As it happened, we did not. We rode out of Abujhmaad as the stars appeared in the sky.

When I went looking for Mangal Ram the next day, his house was locked. So was Budhram’s. I had shared my stories with Damki Bai and the women in Shanti Nagar. But without Sitabai around as a translator, the conversation had been laborious. Eventually, I made my way to the crafts centre. BK Sahu, the manager, had managed to get the district administration to fund the construction of homes for two dozen Maadia craftspeople, including Sitabai.

She had just returned from a trip to Delhi, part of a delegation chosen to represent Chhattisgarh at a government crafts fair. Over tea, I began telling her about my trip to Maad, how I had met Budhram’s niece, Mangal Ram’s mother, seen the Irakbatti memorial dedicated to Jaggu, and how the women at Shanti Nagar had said it was good he was dead.

“Do you know who Jaggu is?” Sitabai asked, arching her eyebrow. “He is Budhram’s younger brother.”

To say I was stunned would be an understatement.

Months ago, when Budhram had spoken of a brother who’d joined the Maoist movement and had been killed, I’d imagined him as a low-ranking, faceless member of the cadre, not a dreaded Maoist leader commemorated by his comrades but denounced by others in death.

Everybody I met since then seemed to know Jaggu. Even the monks at Rama- krishna Mission. They remembered him as a short, athletic boy who stayed and studied at the Mission school till he failed his ninth class exams. “He came to me asking for a waiver,” said the monk who headed the school. “I told him, beta (son), sit through another year in school, get a firm grip on the syllabus, and I would be happy to promote you to tenth class next year. But he was a stubborn boy. He quit and went away.”

For the next year or two, Jaggu stayed in touch with the Mission. He even came back for agricultural training, but then one day the monks heard he had turned into a guerilla fighter. It was not uncharacteristic of Jaggu—as a student, he had been a cadet of the NCC, the voluntary organisation that imparted basic military training in schools. All he had done was exchange a khaki uniform for olive green, and pick up a real gun. He rose through Maoist ranks quickly, breaking one glass ceiling after another. Becoming an area commander was unheard of for a Maadia.

I found myself poring over reports from 2009, the year that elections had last been held—when Budhram had said his brother was killed. Elections had been held nationwide in April that year. In Chhattisgarh, with Maoists announcing a poll boycott, things had taken a bloody turn. According to the South Asia Terrorism portal, which compiles information on Maoist related incidents, the run-up week to polling had seen the deaths of 14 police and paramilitary men, 10 Maoists and five poll officials. There, I spotted this entry: ‘April 9: a CPI Maoist cadre was killed in an exchange of fire with the police in the Narayanpur district (sic). The incident occurred in the Kodenaar jungle area after Maoists opened fire targetting a police party.’

“Jaggu?” asked Amresh Mishra, the officer who’d led the Narayanpur Police that summer. Sharp, mildly acerbic and bespectacled, he was now posted at the Intelligence Bureau in New Delhi. “Yes, I remember,” he said, “I killed him.” The rest of the details, Mishra claimed to be foggy about. All he recollected was leading a patrol party into Maad to sanitise the area a week ahead of polling. “In the distance, we saw a small group of Maoists relaxing under a tree, drinking water at a handpump,” he said. “We had taken them by surprise. They tried to take positions hurriedly, but we were better prepared. It was a big setback for them… their leader Jaggu got killed.”

I asked Mishra about the cases of Budhram and others who had been picked up by the police and allegedly tortured and left in the lurch. “I don’t remember the particulars of any case,” he said, ducking the question on torture. “All I can say is that we picked up only those who we knew had a clear association [with Maoists], and who could give us vital information.” Then, after a brief pause, he continued, “In a strictly legal sense, everyone who lives there is helping Maoists, whether by giving them food or shelter or information, whether willingly or unwillingly. So, yes, we can arrest and question them. They are all collaborators… Of course, only in a strictly legal sense.”

The tracrtor spluttered to a stop, and a few women clambered off, clutching nylon bags. Her limbs were extremely tired, with the digging and carrying of earth all day at the Mission farm. But Damki Bai walked hurriedly towards her hut, dragging her shovel. Her daughters must be waiting. There was dinner to be cooked.

Life in Shanti Nagar had settled into a rhythm, but she missed Abhujmaad. “Here, everything costs money,” she said. “There, all we had to buy was salt. Everything else was free—the air, the water, the mahua, the fruits on trees.” It sounded like a paean to Adivasi life that Maoists sing, replete with the wonders of jal, jungle, zameen. Except, here, it was not a multinational company that had uprooted an Adivasi but Maoists themselves, led by an Adivasi boy whose own brother never returned in fear of the guerillas his brother led.

Supriya Sharma is based in Chhattisgarh and reports for The Times of India. She is currently on a research sabbatical in Oxford

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

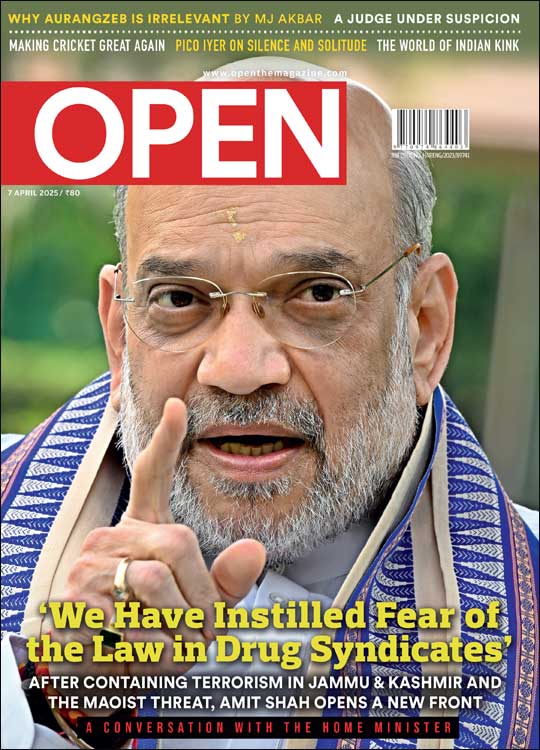

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post

What’s Wrong With Brazil? Sudeep Paul