The Divide and the Design

The violence in Kishtwar bears the signs of an orchestrated plan to create a Kashmir Valley-like situation in this part of Jammu

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

Rahul Pandita

|

14 Aug, 2013

|

14 Aug, 2013

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/kashm1.jpg)

The violence in Kishtwar bears the signs of an orchestrated plan to create a Kashmir Valley-like situation in this part of Jammu

About ten days before violence broke out in Kishtwar, Jammu & Kashmir, a news item that appeared in a Valley publication reported the presence of suspicious masked men with weapons in this town and the adjoining Doda district who reportedly came knocking at the doors of Muslim houses during Ramzan and terrorised them. Though local police officers found these to be a hoax, Kashmir’s junior home minister Sajjad Ahmad Kichloo, a resident of Kishtwar himself, promptly announced a reward of Rs 25,000 for anyone who could catch one of these masked men. It came to naught.

On 7 August, two days before the riots in Kishtwar, the Valley-based separatist leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani claimed during a prayer meeting that Muslims in the state’s Jammu region were being threatened. He asked people to join protests against Village Defence Committees (VDCs).

These VDCs were set up in several parts of Jammu, including Doda (of which Kishtwar was then a part) in the 1990s after militancy broke out there. The VDCs had mostly ex-servicemen whom the Central Government armed to enable them to guard their villages against militant attacks. Today, VDCs have around 25,000 men and some women, mostly Hindus. Across the mountainous areas in Jammu region, where there is no police or Army presence, these committees act as an effective deterrent against militants. In the Doda region and elsewhere, they have been able to repulse many militant attacks. In Surankote area, where large-scale infiltration of terrorists took place in 2003, a VDC of Muslim women helped the Army bust a major terrorist hideout. Sometimes, VDCs have had to pay a heavy price for it, like in one case in 2001 where 15 of them were burnt alive by militants in a village along the Line of Control in the Jammu region. However, in some cases, these licensed weapons have been used by VDC members to settle personal scores or abuse their authority. There have been a few allegations of human rights violations against them.

On the same day as Geelani’s exhortation, posters of Afzal Guru, hanged in February this year after being convicted in the December 2001 Parliament attack case, and militant leader Maqbool Butt, hanged in 1984 on charges of murder, appeared in Kishtwar with messages written in Urdu of ‘Jihad through holy war.’

Kishtwar is nestled in the Himalayas along the Chenab river, about 230 km north-east of Jammu. Carved out as a district from Doda in 2006, the Hindu-Muslim population here is in the ratio of 40:60. In the 1990s, terrorism spread to these parts as well, much like Kashmir Valley, resulting in an exodus of hundreds of Hindu families. Many massacres took place, including the targeted killings of Hindus on a bus and the gunning down of a marriage party. As compared to the Valley, Indian security forces found it harder to fight militancy in Doda because of its mountainous terrain. At one point, this region became a stronghold of the Islamist militant group Hizbul Mujahideen.

As is the case in the Valley, militancy is on the wane in this region too. Security forces have eliminated scores of militant commanders, and the Hizbul Mujahideen has been wiped off. But the influence of Pakistan-based terrorist groups never went away. The three terrorists identified by the National Investigation Agency as key players in the September 2011 blasts outside the Delhi High Court (resulting in the death of 16 people) were from Kishtwar. While one of them, Amir Ali, was killed in an encounter in the upper reaches of Kishtwar in August last year, another one, Chota Hafiz, was killed in December there as well.

In the last few months, tension had been brewing in Kishtwar. There had been at least three incidents of Hindu youth being beaten up by Muslim mobs. In May, posters of Hizbul Mujahideen surfaced in Kishtwar, barely metres away from the town’s police station. The posters issued by the Hizbul divisional commander Amin Butt called for a ‘Jihad’ and warned people against ‘helping the Indian agencies.’

According to investigations by the J&K Police in the last few months, the Hizbul chief Syed Salahudeen, who also happens to be chairman of the Pakistan-based terrorist conglomerate, United Jihad Council, has been asked by his handlers in Pakistan’s ISI to take advantage of the fresh wave of anti-India sentiment in Kashmir after Afzal Guru’s hanging.

Over the past few months, the Hizbul has claimed credit for several terrorist attacks in the Valley that the J&K Police believe were the work of the terrorist group Lashkar-e-Toiba. This, the J&K police believe, has been done to portray that militancy in Kashmir is indigenous. The separatist elements had already been successful in exploiting the situation in Gool area in the Ramban district (neighbouring Kishtwar) last month when four people protesting against an alleged desecration of the Quran died in firing outside a BSF camp. A week after the Gool incident, a security review meeting was held by a senior Army commander of the region. By this time, intelligence agencies had warned of a possible flare-up in the situation, aided by certain ‘separatist elements’ active in the area. Soon, on 29 July, there was an incident of eve-teasing during the local Kalash Yatra, resulting in two youths being injured. “Disturbances had been going on for a month. But the administration did not pay heed to the impending signals,” local Congress leader GM Saroori told journalists. Residents in Kishtwar say that the situation was so tense that many taxi drivers had been telling the pilgrims undertaking the annual Machail yatra to stay away.

Days before Eid, police sources reveal, they had prepared a list of people who were fomenting trouble, but they were prevented by the state’s junior home minister Kichloo from arresting them.

On 9 August, the morning of Eid, Muslims had gathered for prayers at Kishtwar’s Chowgan ground. There were more than 20,000 people in attendance. By an account put together from what eyewitnesses say, what happened was the following:

At about 9.30 am, a separate procession of around 1,000 people from the villages of Pushi, Hullar, Bandarna and Sangrambatta descended upon Kishtwar. These people were armed with guns and petrol canisters, and had Pakistani flags. As they passed through a Hindu locality called Kuleed, people in the procession started shouting anti-India and pro-Pakistan and pro-Aazadi slogans. The mob was confronted by Hindus who asked them to desist from such behaviour. In the meantime, those praying at the Chowgan ground also reached the spot.

In the ensuing chaos, the motorcycle of a Hindu youth who went by the nickname of Chooha brushed a person in the procession, whose mood of aggression had been clear all along. There was an altercation, and in no time, members of the procession opened fire, injuring many people. The rioters then set on fire shops and other properties owned by Hindus. Three people died in the violence that followed.

At several places in Hindu pockets of the town, people retaliated. This included firing by VDC members at several places. Around this time, an arms shop in a shopping complex owned by the Kichloo family was broken into and a number of weapons including forty .12 bore rifles were stolen (reports of some weapons having gone missing from one of the houses owned by Kichloo have also surfaced). Normally, say locals, there is always adequate security during Eid prayers. But this time around, there was hardly any police presence. This meant that mobs had a field day. As they went on a rampage, the police presence was too sparse to deter them. Even where policemen were present, they could only watch as the mobs opened fire and selectively vandalised property owned by the other community.

While Kishtwar was burning, Kichloo and the local police chief and the District Commissioner sat tight in the Dak Bungalow with about 200 policemen. Pritam Kumar,a resident who owns a shoe shop in Kishtwar’s main market tells Open that as his shop was being looted, he had begged the District Commissioner to act. But as the violence spread to upper reaches, Kichloo and his men kept sitting there till evening, doing absolutely nothing. In fact, the J&K Principal Secretary (Home) Suresh Kumar and Police Chief Ashok Prasad were stranded for hours at the helipad without a police escort. “We had been telling the police for a long time that there will be major trouble here,” says Sunil Kumar, a local BJP leader.

It is clear that the state government failed to act on intelligence reports and did nothing to prevent the tension in Kishtwar going out of hand. It was only towards late evening on 9 August, after the Army was pressed into service, that the violence could be controlled. But the question remains: why were the police so unprepared to handle the developments even as they had enough reason to expect trouble? Why did Kichloo stop the police from arresting potential troublemakers? The Hindu-Muslim polarisation here has reached such a level that even those injured in the riots were segregated according to their religion by local authorities. While injured Muslims were treated at the district hospital, injured Hindus were taken to Army treatment facilities and hospitals elsewhere.

The violence soon spread to other parts of Jammu as well. Curfew had to be declared in several areas. But even a day later, the administration was not prepared for the fallout of the Kishtwar violence on other parts of the region. There was violence in Jammu city and some property owned by Muslims was burnt down.

The BJP was quick to cash in on the developments, with senior leaders of the party launching a loud campaign against J&K Chief Minister Omar Abdullah and his leadership. The party not only saw a potential upturn in its electoral prospects in Jammu, it sensed that the Kishtwar violence could reverberate with voters in other parts of the country as well. Modelling himself as a modern-day Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, senior BJP leader Arun Jaitley landed up in Jammu to travel to Kishtwar, but was sent back by the state government. In New Delhi, the BJP then launched a tirade against the Abdullah government in Parliament, with Jaitley saying that the developments in Kishtwar were like a repeat of events in Kashmir Valley in 1990 when Hindus were forced to leave in the wake of Islamist extremism. As the Union’s acting Home Minister (as Shinde was in hospital), P Chidambaram was quick to respond by assuring the House that the Centre would not let that happen.

But that may be easier said than done. The BJP’s protests may be motivated by a desire to score political points, but fears of an exodus of Hindus from the Doda region are genuine. Intelligence reports have suggested that there is an attempt to revive militancy in the region, much like in Kashmir Valley. There are reports of fresh batches of youth from Doda being trained for another round of militancy in this part of the state. This adds to the fear psychosis among Hindus in Doda. The Hindu business community has threatened to move out unless the government provides them adequate security. “We have faced a similar situation in the 90s as well, but that was of lesser magnitude,” says Rakesh Gupta, president of the Kishtwar Chamber of Commerce, whose garment store was burnt down by rioters.

Succumbing to pressure by the BJP and other political parties, Omar Abdullah has ordered a judicial inquiry into the Kishtwar events. This pressure also led to the resignation of Kichloo, which was accepted by the CM without ado. On 13 August, the Supreme Court asked the J&K chief secretary to file a detailed affidavit on the Kishtwar clashes and subsequent steps taken by the state government.

Four days after the riots, the state government arrested 11 people in Kishtwar, including two policemen. But right afterwards, Omar Abdullah launched a counter attack against the BJP on Twitter, citing the 2002 riots of Gujarat to make his point. Leaders of the Congress party, Omar’s allies in J&K, cautiously reacted to this by saying that two wrongs did not make a right.

At the time of filing this story, Kishtwar is still under curfew for the sixth day. Many incidents of violence have still been reported, despite that. The Centre has now moved in extra columns of the Army, but the division in Kishtwar is complete. On his part, Kichloo defended himself by saying that he did his best to salvage the situation but did not specify what exactly he did. His party later claimed that he was trapped himself and had to scale a wall to escape. In an interview to The Indian Express, he claimed that the Kishtwar riots had been planned for two months; by whom, he did not specify.

But as is clear from the sequence of events in Kishtwar, Kichloo and others in the state government did not act on that information. If he had known of any such plan, there should have been an adequate mechanism in place to thwart the violence. That is why Kichloo has a lot of explaining to do.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

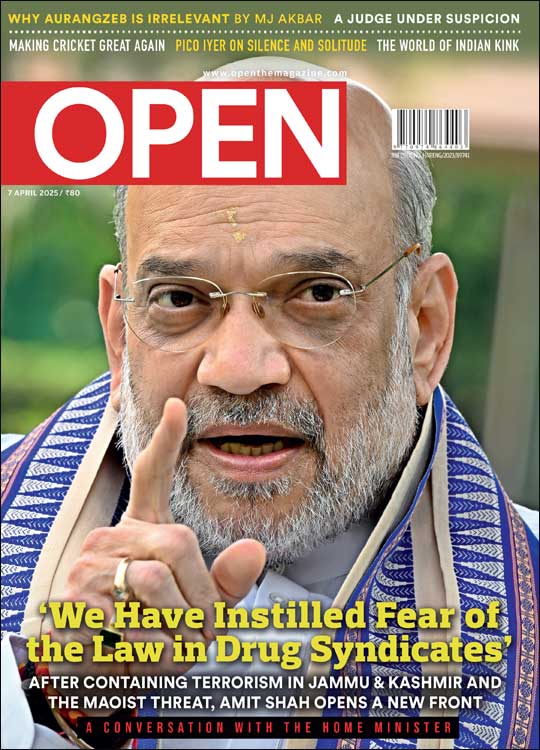

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post

What’s Wrong With Brazil? Sudeep Paul