Life after a Life Sentence

Some of them spent their best years in prison. They were young when they went in and middle-aged when they were released. Some are still serving time. What does freedom mean to such people? Here it is in their own words

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

|

13 Aug, 2009

|

13 Aug, 2009

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/imprisonment-lead.jpg)

What does freedom mean to people who have spent their best years in prison?

L Prakash

43 WHEN JAILED, 51 NOW AND STILL SERVING TIME

I was Chennai’s best known hip replacement surgeon and secretary of the Indian Orthopedic Association. I was sentenced to life for making pornographic films and posting nude pictures of my women patients on the Internet. This is my eighth year in jail. I believe I am innocent.

Before being imprisoned, I had only written prescriptions. In jail, boredom and loneliness turned me to writing. Now I have authored 102 books, including fiction, non-fiction, self-help, comedy, romance and a Mahabharata version in four volumes. At least five are on my favourite subject—erotica. A dozen have been published. Before venturing into fiction, I wrote seven self -help books. They contain tips to change one’s lifestyle, ensure victory in life, gain photographic memory and follow guerilla warfare techniques for living in the jungle called society.

My first fiction work, Master of Time, is now in the editing stage. Its main characters are Bhima, Arjuna and Yudhishtira. The story is set in the Jurassic age. My wish is to write at least 450 books before I die. It will be a world record.

In some respects, jail life has been a blessing in disguise because murderers, rapists, thieves, terrorists, traitors and corrupt elements share their stories with me. In prison, I am also remorse-free over the circumstances that led me here. A prison can only restrict the movement of your body. Nothing can curtail the freedom of your mind.

Public attitudes against pornography were strong when I was arrested. But society has changed since. I have no regret over whatever happened in my life. If I am exonerated, I will go to a place close to Maya Bandhan in Middle Andaman. A 100 acre estate is available there between dense forests and the sea, and the nearest human presence is about five km away. I will stay there with a few servants and write books for the rest of my life. A four -wheeler vehicle and a boat will be my links to the outer world.

The situation in jail has changed a lot. It was not easy to write in the beginning. First, I had to get special permission. Then note books and A4 sheet paper were not available. There was no electricity in my cell initially. So I had to ask for a small kerosene lamp. Now there is electricity and permission to use a desktop. There is no Internet, but I am happy.

(L Prakash spoke to KA Shaji)

Kamini Balu Ingle

24 WHEN JAILED, 41 WHEN RELEASED

I was arrested for killing my husband’s second wife and my case is dated eighth of the eighth month the year after Indira Gandhi died. Three years later, in 1988, I was sentenced for life. When I first entered jail, I thought, 15-20 years, how will I ever get out? My son was four years old and my daughter five when I went to jail. When I came out, she was the mother of three children.

The first time you see a jail is bhayanak (scary). It’s a like a bhootkhana (ghost chamber). I remembered my children every moment. I couldn’t sleep because thoughts about them—where would they be, what would they be eating, who are feeding them—would keep repeating in my mind.

In 2005, as the date of my release approached, I was constantly hounding the jailer to take me to the office to ask for the date of my release. One Monday afternoon, the jailer told me, “Kaminibai, have some food.” I told her I couldn’t because I was on a fast. She insisted and then even she ate from my plate. At 2 pm, the paper came announcing my release. Even before I could react, the entire barrack erupted in emotion—some were laughing, some crying, some jumping with joy. All I could think was when will the lock open and when could I go out. There was much happiness in my heart.

My parents and children cried a lot when they met me, but I cried more than them. The best thing now is being with my family. Especially that despite having served a jail sentence, my husband is with me. He has married again, but so what? We all live together. I am so lucky that I have got my life back after coming out of jail. Not everyone gets that. If something breaks, then it is very difficult to join it again.

Paul Kripashankar

28 WHEN JAILED, 44 WHEN RELEASED

I am a Singaporean. By the time I turned 20, I was smuggling dollars and gold into India. I became connected to the Mumbai underworld. In 1991, when my wife left me with our daughter, I strangled her to death in Kurla (Mumbai). I was sentenced to life.

Jail wasn’t too bad because I had money and underworld links. Then something happened in 2000. I was in Kolhapur jail when some Christian prisoners sought my help in starting a Sunday church. I was not even a Christian; my name had misled them. But I started going to their gathering. Soon, I was giving a sermon every Sunday. These sermons changed me because I was spending hours preparing for them. In 2001, during my high court appeal hearing, I suddenly asked the advocate to withdraw the case. I told the judge, “My conscience is not agreeing.” Once back, I cut off my underworld links. On my request, I was transferred to Yerwada jail in Pune.

I had often applied for leave [prisoners usually get a two-week annual leave called furlough; during family emergencies, they also come out on parole] but it would be refused because of my foreign citizenship. Finally I went to court. In July 2008, after 16 years in jail, I was given two weeks’ furlough. Once I stepped out, I didn’t know where to go. A part of me even wanted to go back. My picture of life was just walls, some trees and prisoners walking around. I couldn’t relate to the outside world. The third day I came to Mumbai, but all the landmarks I knew didn’t exist. I saw so many dazzling vehicles. Even sleeping on a mattress felt weird. It was like a leap into something else.

I tried looking for my daughter then. I learnt that she was with my in-laws in Gujarat. I went on a bus, but as soon as I reached Surat, I heard people talking about the serial bomb blasts that had happened that day. I returned in the same bus. I was afraid that if the police stopped me, they would implicate me in the blasts.

When it was time to return to jail, my mind was asking me to escape. I could so easily disappear. But my feet took me back to prison. I was miserable for a time. I missed all the television serials and movies that I had begun to watch outside.

If I had not returned that day, I would have been an absconder now. Instead, I am now a free man because three months after I returned, last December, my release orders came. I am now part of a trust that takes care of underprivileged children.

If you want to be really free in life, don’t think about yourself, do something for other people. If your thinking is right and is beneficial to someone else, doors will open everywhere.

Prabhakar Gaikwad

26 WHEN JAILED, 47 WHEN RELEASED

I was in jail for 20 years, seven months and 13 days. I had been to my sister’s house for bhaubeej when her neighbour came and started abusing her. I tried to talk to him and when he didn’t listen, I stabbed him to death. This was 14 November 1985. In five months and 28 days, I was sentenced. The day I went to jail, I was 26 years, four months and 18 days old. When I entered jail, there were 55 murder convicts. I was the 56th. My entire jail term was spent in Amravati jail, 10 km away from home.

The routine in jail is never-ending. Our wake-up time was 5.30 am and if we didn’t get up, the warder would kick us. Then he would take a headcount.

At 6, the locks opened and we went from the barrack to the work section. Lunch would be at 10 am. The food was really bad earlier. We had to remove grass, pebbles and even nails from it. The roti would crumble in our hand. After lunch, we would rest and then work till 4 pm, which was dinner time. But no one felt like having dinner so early, and would smuggle food into the barracks. Often, the jailers would raid us and throw the food away. At 6 pm, the barracks would close. By 9 pm, we had to go to sleep. We could not even talk after that. Jail can make people go mad. It has happened before my eyes. Tarachand Joshi was an old prisoner, sentenced for 26 years. He had already spent 18 to 19 years and was a respected man. After he got into a fight, the jailers beat him naked in front of everyone. He became paranoid and aggressive, abusing everyone, including jailers. They put him in solitary confinement for four or five years. He went more mad there.

My first leave was after five years. The first few times, I went back on time. But when I came out on parole for my parents’ death and my daughter’s marriage, I didn’t go back. I would wait for them to come for me. I would be constantly looking outside to see whether the police were there. If a guest came, I would not sit with him thinking what if the police came now. That was a bigger punishment than prison.

The days go slow when your release comes near. I would look at the hands of the clock and feel like turning them to make it go faster. But you should control your emotions. One man I knew, a life termer, had been in jail for 14 years. His release orders came and in the evening, he was getting ready to go when he fell down and died. You should not be too happy either.

Just yesterday, I dreamt that I was in jail. The prisoners were sleeping in the barrack and I was going and telling them, “Get up. Why are you sleeping, get up.” I got up and told my family that I had seen this dream. They told me to never mention jail in the house.

Prashant Mande

25 WHEN JAILED, 32 NOW AND STILL DOING TIME

I worked for a fish wholsesaler in Akola as an odd-jobs man. Our relationship soured when a land deal between us didn’t work out and he delayed returning my advance. During that period, I became friends with three rowdies. During our drinking sessions, we started talking about kidnapping my seth’s 16-year-old second son. On 28 October 2002, my maalik gave me Rs 500 to go to Pune. In the evening, my friends came with a vehicle to kidnap the boy. I told them I had to go to Pune. “You come for two minutes,” they said, “Don’t do anything, just be there when we kidnap him. Then we will drop you to the station.”

When we reached outside the shop, our target had already left. Instead, we saw his elder brother Naresh coming on his bicycle. I hid inside the jeep and my friends told him, ‘Yaar thoda dhakka maar.’ They pushed him in and I bound him. We then took the jeep about two kilometres from the village, a little away from the road. When the ransom call was made, his father didn’t say anything. Soon, we saw four or five jeeps with villagers and the police. We fled and later agreed that the boy must be killed because he would reveal our names. Everyone was saying I am not doing it, you do it. Finally, I slit his throat. We buried him in a ditch and then left. On the way we realised that there was no diesel to reach the station. There was a restaurant on the way. I knew the owner and took some kerosene from him. After we left, the search party came to that hotel to have tea. While talking, someone happened to say that I was in Pune. The hotel owner told them, “No, I just saw him.”

They picked me up from Pune. I was given a life sentence. But it was my mother, wife and child who suffered it. They had to leave the house and village. My wife became a daily labourer to make ends meet. After three years, I got a 15-day leave. After I reached home, my wife told me that she would stay at home during my leave period. But we needed the money. I told her both of us would go for work. During those 15 days of freedom, I worked as a farm labourer. With the money, I bought a dress for my kid, chappals for my family. When I went back, I was crying aloud.

After that, I have come out on furloughs and parole and every time, I have worked. I dug wells or did farm work or construction labour. My wife has now had an appendix operation and that’s why I am out on parole now. So that I can work and keep the family going. I have at least eight years left to go. The greatest joy in life is to see your little children grow up. But I will not experience it. When on leave, every day feels like a year. For me, azaadi is 15 days of leave, otherwise it has no meaning for me.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

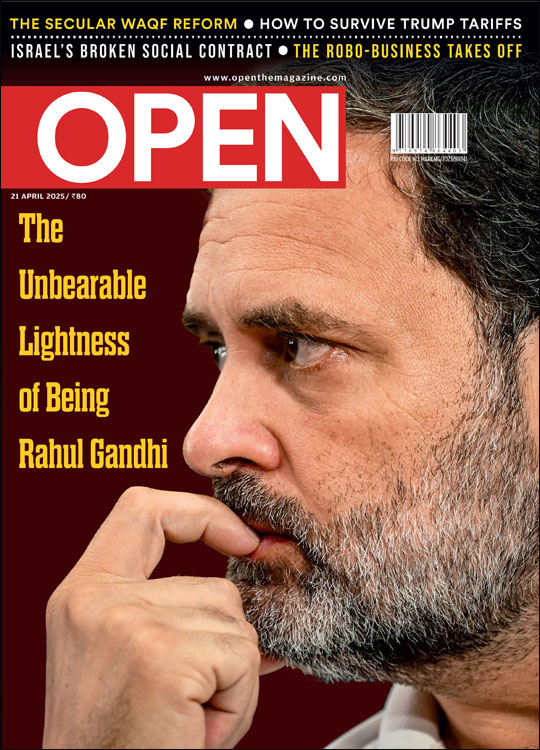

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Rahul Gandhi

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

Finding Ferdinand Kittel Babli Yadav

Ukraine silently encroaches on ‘friendly’ Moldova Ullekh NP

NFRA chief Ajay Pandey joins AIIB Rajeev Deshpande