Collateral Clean-Up

It may not entirely be a sense of duty that is motivating CBI Director Ranjit Sinha

Mihir Srivastava

Mihir Srivastava

Mihir Srivastava

|

08 May, 2013

Mihir Srivastava

|

08 May, 2013

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ranjit-sinha.jpg)

It may not entirely be a sense of duty that is motivating CBI Director Ranjit Sinha

As the Indian Government seeks to deal with the strongest indictment of the political executive by the Judiciary in the country’s history, and India’s Prime Minister struggles to hold on to office, the sequence of events that led to this controversy can be traced back to internal rivalries between senior ministers of this government and a CBI Director whose very pliability led him to first collude with the Government and then come clean in a bid to save his skin.

The leak—to the media—that Law Minister Ashwani Kumar and others vetted the CBI status report on coal allocations and kept the apex court in the dark did not originate from the CBI. A member of the Union Council of Ministers confirms to Open that the leak originated from within the Government. According to him, there is a strong ‘Punjab group’ in the Council of Ministers, chiefly lawyers who are articulate in English and love to hate one another. One such senior member of the Cabinet—who was in the reckoning for the post of India’s Law Minister and is perhaps still hopeful that he will get this coveted ministry if the Government survives this crisis and Ashwani Kumar is shown the door—informed a newspaper journalist that a sealed CBI report on the role of the Government in the allocation of coal blocks from 2006 to 2009, when Prime Minister Manmohan Singh held the coal portfolio, was modified secretly by Ashwani Kumar (who too is a member of the Punjab group) to suit the Prime Minister.

The reporter visited the Law Ministry to check the claim’s veracity. A highly placed official in the Ministry briefed him and confirmed that the tip-off was genuine. Another journalist of the same newspaper paid a visit to Ranjit Sinha, a 1975 batch IPS officer of the Bihar cadre who took over as Director of the CBI in December last year, to reconfirm the information. Sinha immediately sensed the seriousness of the matter.

For Sinha, the leak was a larger concern than the tampering of the CBI report. The agency’s investigation is being conducted under the supervision of the Supreme Court, and even Attorney General Goolam E Vahanvati had stated in court that he had not seen the report. In fact, the CBI assured the apex court that the political executive did not have access to it. But that was not the version that would appear in Indian newspapers the next day.

Sinha rushed to his immediate boss, Minister of State in the Department of Personnel, V Narayanasamy (the PM is also in charge of the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, which has administrative control over the CBI), to inform him of the development and take him into confidence, according to a senior functionary of the CBI who witnessed the drama. There were two options available to Ranjit Sinha: keep quiet and risk becoming a scapegoat or turn the tables by stating the truth.

Thus it was that the CBI Director filed an affidavit that the agency’s report on Coalgate was vetted and changed by Ashwini Kumar and joint secretary level officers of the PMO and Coal Ministry, Shatrughna Singh and AK Bhalla, respectively. The CBI even provided details in the affidavit of portions of the report that were changed after a series of meetings attended by Kumar and Vahanvati and held between February and early March this year.

The Director was not only trying to save his neck, he had reason to be annoyed by Ashwani Kumar whose arrogance and zest for copy-editing had already annoyed several government officials. According to some CBI officials, the Law Minister’s conduct at a meeting held on 6 March bordered on the rude. He looked at the report in the presence of Vahanvati and Sinha and reprimanded Sinha for its poor drafting. “Aap ko English nahin aati kya?” he reportedly asked, and started editing the hard copy of the report using a pencil. The Minister had his own staff make changes in the text right there, say CBI insiders, and then his office forwarded the revised draft directly to the PMO for a second round of vetting.

The interest shown by the Minister and the PMO was a direct result of the stakes involved. CBI sources reveal the people who are likely to find adverse mention in the report include Coal Minister Sriprakash Jaiswal and former Tourism Minister Subodh Kant Sahay, apart from Congress MPs Naveen Jindal and Vijay Darda. The role of the PMO is also likely to come under scrutiny.

That became clear at the Congress’ ‘war room’ meeting at 15 Gurdwara Rakabganj Road that took place soon after the matter became public. It was attended by such members of the Punjab gang as Kapil Sibal, Pawan Kumar Bansal and Manish Tewari. According to one of the participants in the meeting, Ashwani Kumar was given two options: make a statement in Parliament and come clean on the issue, which could then become the basis of the party’s defence, or simply tender his resignation. The war group meeting concluded that Ashwani Kumar had to go since he was refusing to make a statement in Parliament. “You have become collateral damage to the Prime Minister,” he was told by a senior congress functionary, as an argument ensued. “I have become collateral damage due to the PM,” Ashwani Kumar is said to have retorted. But it turned out he didn’t have to quit because the PM and his men supported him; the PM had put his foot down, according to a member of the Council of Ministers. The PM was of the view that if any action was taken against Ashwani Kumar, it would amount to acknowledging guilt in the Coalgate scandal and that would put the PMO in the direct line of fire. This failure of the PM to act at a time when instant action could have warded off damaging Supreme Court observations is what is currently haunting the Government.

Sinha’s desperation to save his own job, it seems, led him to contradict the Minister’s initial response that he had only made some ‘grammatical corrections’ in the status report. The Court affidavit filed by Sinha suggests that the Minister had more than mere grammatical changes. He deleted a sentence on the legality of the allocation of coal blocks while a legal amendment of the allotment process was in the works. It was clearly done to limit the scope of the CBI probe, as one of the main allegations against the Government was that it went on allotting coal blocks despite its awareness of an impending proposal to auction them. It was an obvious bid to insulate the PM, who was in charge of coal, from the heat of Coalgate.

While exposing the role of the Law Minister, Sinha also qualified his affidavit by stating that the CBI allowed no substantive changes in its report; he said that no accused individual or suspect had been let off and the findings of the report had not been tampered with.

That was in keeping with Sinha’s previous record in service, and it was by no means the first time he had attracted such attention. In the late 1990s, as DIG in the CBI, he had investigated the fodder scam in which former Chief Minister of Bihar Lalu Prasad Yadav was one of the accused. The Patna High Court had passed similar strictures against the CBI for presenting a watered down version of its report on that scandal. Sinha’s senior officer UN Biswas, joint director (East) of the CBI, told the Patna High Court division bench on 3 October 1996 that the report submitted by Sinha was doctored. He alleged that the report had diluted the charges against the accused. Biswas is said to have apprised the court that the original report prepared by him had facts that could clearly pin guilt.

That episode is what led activists Arvind Kejriwal and Prashant Bhushan to question Sinha’s appointment as CBI Director. They argued that Sinha’s moral integrity had been questioned in the past when he was reprimanded by the Patna high court for favouring the then Chief Minister Lalu Prasad in the fodder scam case.

In July 2001, the then leader of opposition and now Deputy Chief Minister of Bihar, Sushil Kumar Modi, urged the then governor Vinod Chandra Pande to direct the state government to sack ‘tainted officers’ such as Ranjit Sinha and AB Prasad. They were both posted in Delhi at the time. The Bihar government created a new post of ‘officer on special duty’ to accommodate Sinha at Bihar Bhavan after the expiry of his term in the CBI and gave him the special task of “influencing the outcome of the fodder scam investigation” in favour of Lalu, as Sushil Kumar Modi had alleged at a press conference back then.

Sinha’s appointment as CBI chief was later supported by both Nitish Kumar—who is now Sushil Kumar Modi’s boss in the Bihar government—and Lalu Prasad Yadav. But Sinha’s appointment to the post finally came through only thanks to a tussle between the Congress party and its Government. There were three names in the reckoning for the post: Neeraj Kumar, currently Delhi Police Commissioner, SC Sinha, director general of the National Investigation Agency, and Ranjit Sinha. While the PM’s supporters were keen on Neeraj Kumar, Ranjit Sinha had the backing of the party—which suggests he was the candidate favoured by 10 Janpath.

But Sinha’s past history of political closeness to people who could help him in his career and his willingness to act in their interest also had its flip side. It angered politicians who were opposed to his patrons. It was Lalu as Union Railway Minister who ensured that he took over as Director General of the Rail Protection Force (RPF), even holding the post vacant for three months till Sinha was ready for it. (It is Sinha’s tenure in this paramilitary force that later strengthened his case for taking over the Indo-Tibetan Border Police—and then the CBI.) But when Lalu left the Ministry and Mamata Banerjee took over, her team treated Sinha with suspicion because she distrusted Lalu’s appointees. It was Mahesh Kumar, a railway official who was close to Banerjee, who was instrumental in Sinha’s unceremonious exit as RPF chief. Banerjee even wrote a letter to the PM asking for his ouster.

It is considered a common truth in political and bureaucratic circles that it was the abovementioned bitterness that made Sinha place Mahesh Kumar’s activities under the watch of his sleuths once he assumed charge of the CBI as its chief. Sinha even had Kumar’s phone under surveillance, according to a report by Malayala Manorama.

Mahesh Kumar reportedly wanted Vijay Singla’s help to switch from being a Railway Board member in charge of ‘staff’ to one overseeing ‘electrical’ matters. Contracts worth thousands of crores are given out each year by this department of the Railways. When the controversy over the editing of the Coalgate status report broke out, the raid that led to the arrest of Mahesh Kumar was also one way for Sinha to pitch the fact that he was indeed acting independently as CBI Director.

But this investigation took an unexpected turn and caused a major embarrassment to the Government once Bansal’s involvement hit headlines. Interestingly, this time Sinha did not brief the Government on this expose, says a junior colleague of his in the CBI. “He is a typical cop who means business and has a sharp mind. He is not going to budge under pressure and has strong survival instincts. He is not going to give in easily,” he says.

Sinha’s problem is that he may have left himself no way out. By seeking to please the Government and agreeing to amendments in the CBI status report, he has come in for harsh criticism from the SC, and by failing to keep the Government in the loop on the Bansal case, he has angered the very people who ensured his appointment. But he has a fixed two-year tenure and unless the SC asks him to go, he could well outlive this government.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

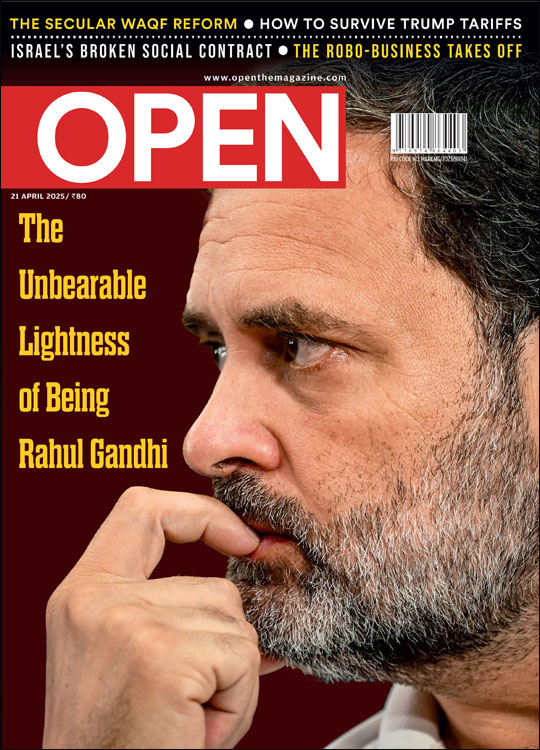

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Rahul Gandhi

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

AI powered deep fakes pose major cyber threat Rajeev Deshpande

Mario Vargas Llosa, the colossus of the Latin American novel Ullekh NP

Speculative History Shaan Kashyap