Finding My Memory

How a man with short-term memory remembers the moments of his life

Charles Assisi

Charles Assisi

Charles Assisi

|

08 Apr, 2013

Charles Assisi

|

08 Apr, 2013

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/memory.jpg)

How a man with short-term memory remembers the moments of his life

To cut a long story short, a little over two years ago, some neurons misfired in my head. I was in my office when this happened. I won’t get into the sordid details and drama that accompanied the episode—except that my colleagues were witnesses to my falling down in a heap, frothing and convulsing. A couple of them bundled me into a car and drove like maniacs to a hospital where I was admitted into the intensive care unit.

A month after I was discharged, my family and friends were told a virus had invaded my immune system, permeated the blood-brain barrier, damaged some parts of my brain, and triggered a bout of viral encephalitis—a rare disorder with high mortality rates in some conditions. I was among the ones who survived.

The only problem is, survivors have to deal with various kinds of complications. In my case, I had lost my memory. I had no idea who I was, where I was, what I did, where I lived, and save a few people close to me, who everybody around was. For all practical purposes, I was dead. But I was breathing, most of my other faculties were still intact, and I hadn’t forgotten the language.

To draw an analogy, think of the hard disk on a computer. When you need to access something out of it, you punch in a few commands, the computer accesses its random access memory (RAM), tells the machine where the files are stored on the hard disk, pulls it out, and delivers on screen.

When the RAM gets damaged, though, there is no way you can be sure the computer knows which part of the hard disk to access. So while the information may reside on the machine, it may or may not be accessible. Often, when made accessible, the data is corrupted.

That, in a nutshell, explains why while I had lost my memory, there were some ‘good sectors’ in my brain that permitted me to remember a few people, and how to use a computer, and how to walk, talk and breathe. Unlike with computers, though, the ‘corrupt RAM’ couldn’t be pulled out of me and replaced.

The doctors attending to me told my family it would be a while until I recovered completely—at least five years, they guessed. They threw in a caveat as well—what I’d remember and how much, they’d be hard pressed to predict.

Between my wife, brother, parents and a few close friends, they took turns to tell me who I was. But I’d forget in a few minutes and get back to being a body of nuisance to pretty much everybody around by repeating the same sets of questions. Now, how do I know all of this happened? Because my wife Anna began compiling a notebook that outlined in detail answers to my questions. My brother Kolya tried to explain what was happening in my head. And my cousin Niffy wrote me long notes of events, places and things from our younger days when we were growing up. My colleagues at work—IG, Dinesh and Peter—pitched in by trying to help put in place the pieces of my day job as a journalist.

Fast forward. THE damaged tissue in my brain started to heal and my memory improved from being able to hold information for a few minutes to about 24 hours. A gentle counsellor, whom I was assigned to, told me it was time I took over Anna’s note-taking duties. Those notes, she told me, would hold my memories. Without it, she told me, I’d never get my freedom back. In hindsight, that was one of the best pieces of advice anybody offered me.

To do that, I wrote to myself, I ought to think of myself as a company that had gone bankrupt. But now there is a new CEO in place with a mandate to turn it around. I guess I derived the metaphor from the fact that I trained as a business journalist and it was embedded in my psyche. The question was how.

The most obvious thing to do, reason told me, was to make an attempt at reclaiming my past. If I did that, I’d perhaps be able to put my present in context. Fortunately, like I said earlier, I hadn’t forgotten how to use a computer. But because I am a bit of a security freak, my machine was password protected and the information encrypted. Only I knew the passwords. If I could ‘hack’ into my machine, I could begin my journey.

Contrary to what most people believe, there is no rocket science here. ‘Hacking’ in geek lingo simply means ‘to look into’, in much the same way a mechanic would at the engine of a car. But they need tools to do it. For the Windows-based machine I used to work on then, I turned to a lovely little piece of free software called Ophcrack. It is available for download on ophcrack.sourceforge.net. A little bit of tinkering around, and I got into my hard disk.

After that, things were easy. My primary internet browser is Chrome. Extracting passwords to all of what I needed was a piece of cake by deploying yet another tool called Chromepass. That done, I was in business.

Some days of browsing through thousands of emails, my Facebook and Linkedin accounts, Twitter handle, and the notes I maintained along the way, things started to fall into place. I started to get some sense of who I was. Also, it helped me put faces to the names of people in my phonebook, most of whom I’d forgotten. If they weren’t on Facebook, Linkedin or part of my email trail, I’d be totally lost.

So if anybody outside my notes or social network called, I thought it better ignoring them. Reason told me if somebody’s name flashed on my screen, I ought to have met the person someplace. But without knowing the context of how I know the person, what conversation could I possibly have? But more importantly, having somebody’s number in your phonebook doesn’t mean you trust the individual.

In any case, if somebody told me something, I’d have to accept it at face value. It was their word against mine. And my word amounted to nothing, even to me, because I had no memory and therefore no context.

I was running out of time. Maintaining a notebook to keep track of things was beginning to get painful. It was getting bigger. The bigger it got, the more difficult it was to access the information in it. Things had to be automated; and I had to find a way to sift through whom to trust and whom not to. Emotions had to be reined in as well. Because even I didn’t know whether my emotions were real or chemically induced by the potent drugs I was on. Simply put, I’d have to outsource my memory, emotions and decision-making capabilities to more reliable sources.

After relentless research of what is possible, I stumbled upon a bunch of people who believe in quantifying everything (quantifiedself.com). The underpinnings to the philosophy here is that what cannot be measured or tracked cannot be managed. Believers in the Quantified Self movement go into as much detail as possible, like the food you eat and the calories you consume, the number of hours you sleep, the amount of time you spend at work, the number of times you have sex, and anything else you can think of. They love to share this data with other people and compare notes. As a thumb rule, I don’t share.

That said, this movement ties into a larger philosophical framework that I have come to believe in fiercely. When it is time to die, how will you measure your life? Did you live a good life, did you live a bad life, what regrets do you have, what is it you wish you did, what is it you wish you didn’t? This framework was first articulated by one of the finest business teachers of our times, Clayton M Christensen, in a talk delivered at Harvard. The talk can be viewed on Measureyourlife.com. Since then, he’s gone on to write a book on the subject, How Will You Measure Your Life? and deliver many talks.

While the Quantified Self movement is a very here-and-now thing, Christensen looks at life from a more holistic perspective. To my mind, both had to be married if I had to get on top of the predicament I found myself in.

To do all of these, I looked hard at the possible technological solutions. The first and most powerful tool I discovered was a piece of software called Evernote (Evernote.com). Simply put, it is a note-taking software, but with very advanced capabilities. It allows me to create folders and file everything away both on my computer and on a cloud. That means, all of what I want to keep track of is available to me anywhere, anytime. So at the end of every day, however worn out I am, I take time off to write a note to myself on everything that had transpired through the day. That goes into a folder called ‘Notes to Myself’. If I choose to, I can make an audio file as well or a video clip for that matter and tag it appropriately.

Every place I visit and every individual I meet, I surreptitiously take pictures of on my BlackBerry and email it rightaway into my Evernote account. At the end of every day, these images are tagged with names and the context in which they were taken. Everything I read online is electronically filed away into Evernote with a single click on my browser into a folder of my choice. If it’s from a book I need to keep track of, the relevant passages are photographed instantly, tagged and emailed from my tablet or smartphone into Evernote for future reference.

But keeping track of conversations at the end of every single day can be a painful affair, particularly when it comes to professional meetings. To get around that, I discovered yet another hopelessly ingenious combination of hardware and software called Livescribe (Livescribe.com).

On the face of it, Livescribe looks like a regular pen and notebook you write on. But the thing with this pen is that it has a built-in audio recorder on its head and a camera embedded next to its nib. What it allows me to do is that while in the middle of a conversation, I don’t have to take copious notes. Instead, I just make notes of the main points like anybody would at an official meeting.

So when it’s time to review the conversation, all I’ve got to do is simply switch my smart pen on and tap it on a part of the note I need to review. The inbuilt camera identifies the point at which the note was made, picks up the audio track relevant to that part of the conversation, and plays it back for me. Livescribe’s real power kicks in when I plug it into my computer—the accompanying software imports the audio files from the pen’s recorder and the notes I’ve made from its embedded camera and synchronises it with Evernote.

So when I open my Evernote account, I can scan the notes, and simply click any part of the audio I need to review. What makes it even more powerful still is that Google’s search engine can be embedded into Evernote. But lugging a laptop around and booting it when you need information on the fly just as you run into somebody can be a pain. To get around that, I got myself an iPad and an iPhone.

So if I run into somebody I met a few days ago and have no clue what is it we’d spoken about, all I’ve got to do is look up my phone or tablet on the sly, and all the information on my last interactions with the person flashes onscreen. It allows me to carry on as if nothing happened. There are times, though, when I don’t have any background material on the person. The only thing you can do then, I figured, is simply smile, ask vague questions, provide vague answers, and make a hasty exit.

It amuses me no end because over time, I’ve figured most people are easy to deal with. If you’re nice to them and demonstrate empathy, people open up and let you into their lives in ways you would otherwise not imagine. I’ve ended up striking deep and meaningful conversations with people and getting to understand them better because I have no context, baggage or biases anymore. Nothing has driven home the point harder for me that it’s good to be nice to people than this entire episode.

On my iPhone, I’ve got another piece of software called Daytum (Daytum.com). This is my ally in trying to keep track of everything I do, the Quantified Self way. Over time, the data I’ve gathered clearly demonstrates that on days when I have gotten less than seven hours of sleep, my memory begins to falter.

It has also allowed me to derive a relationship between the amount of food I consume, at what time, and my memory. So I now know for a fact that if I don’t get a certain amount of glucose into my system before 11:30 am, I’m going to have a tough time trying to access information from my head, however hard I may try.

The reason, I figured, is that when there is neuronal damage, your brain consumes larger amounts of glucose than most others’. Which is why I crave sugar. If I hadn’t measured this very specifically and started replenishing my body with sugar at a certain time during the day, my craving would have translated into binges, I’d end up consuming more sugar than what I need and face longer term health risks of an entirely different kind.

Having a tablet and smart phone with a 3G connection also allows me to find my way around places. The thing is, though I’ve lived in Mumbai all of my life and know this city like the back of my hand, my sense of direction is a complete mess. But with either of these devices on hand, I have my very own Global Positioning System (GPS) that allows me to find my way. While all of these help me get around my daily tasks unhindered and keep my life in control, emotions are a different kettle. How do you deal with emotions using technology? Like I said earlier, there are times when I don’t know if my reactions are natural or chemically induced. The problem is, the choices you exercise here, by their very nature, have nuances and implications that aren’t obvious instantly.

To my mind, while not the perfect solution, there is a way to measure consequences and therefore priorities. To do that, though, I go back often to the philosophical framework outlined by Christensen and the Quantified Self Movement.

To understand the probability of those decisions being the right ones, I spent an awful lot of time studying game theory. It may sound ridiculous because this is a branch of mathematics concerned with the analysis of strategies to deal with situations when faced with various outcomes. It has been used in business, war and biology.

To my mind, though, I am fighting a war, and any weapon I can use, I will grab with both hands. I’ve come to a point now where I am convinced game theory ought to be made a mandatory part of education.

Researching what course is the right one wasn’t easy. Some of the best courses are available on Thegreatcourses.com. But these are courses you pay for—and they’re well worth the money. One of my favourites is one I took on music theory by Professor Robert Greenberg.

Coming back to game theory, though, I finally settled on Ben Polack’s course offered online by Yale University. His lectures are easily the best on the subject and can be accessed on https://oyc.yale.edu. The thing with game theory is that it allows you to look at the choices staring you in the face. To make those choices, a visual tool that allows you to map all that’s going on in your mind is another ally worth having on your side. While Think Buzan (Thinkbuzan.com) is a good option, and which I recommend highly, I ended up going with a tool called Free Mind (Freemind.sourceforge.net). It’s free, and for somebody as geeky as I am, this does the job well.

After the outcomes are visualised and the strategies decided, you’ve got to execute them. To execute them well, you again ought to prioritise when, where and at what time you will. To do that, I use Omnifocus (Omnifocus.com). There are tablet and smartphone versions of this tool available and it gives me a good idea of what is realistically possible, what isn’t, how much time it will take, and whether or not it is worth the effort I may end up putting into it.

Thanks to all of these tools, my mind is more focused now, and I can be clinically ruthless with the choices I make. I used to be a social animal with friendships I always thought ran very deep. But, embedded into these models, those friendships now seem shallow and ones that demanded a lot of energy to sustain.

I don’t have the bandwidth to expend on what is not needed. When you see it so dramatically, with the aid of a combination of mathematical models and software, you end up being ruthless in weeding people out of your life. Doing it may seem tough. But once you’re done with it, the benefits are obvious. There suddenly seems so much more time on hand and peace on call.

And finally, all my notes, when I look them up, I know are descriptions of events in much the same way that news reports are. Daytum tells me my memory is now reliable for 15 days on its outer limit. After that, it evaporates. So when I now talk to people about something that I had spoken to them about earlier, most people appear to be inconsistent. They have differing versions of an event as it took place. To my mind, it is ample evidence that memory is elastic and morphs to suit a person’s current reality. So while empathy and compassion are good, it’s good to know where to draw the lines.

A few months ago, I hired the services of a certain gentleman to teach me kickboxing. I’d taken an instinctive liking to him. I was candid, told him what my problem is and that he’d perhaps have to expend a little more energy on me than he would with his regular clientele. He swore God he would. But he added he keeps three months of fees as advance. After my conversations with him, I input the variables into my mind maps and deployed the lessons I’d learnt from game theory. My model told me the probability of his disappearing with the money were high. My instinct told me otherwise. Instinct, incidentally, is nothing but a function of your accumulated memories. I gave in to my instinct and paid him. He disappeared. My model predicted he’d call in roughly 12 weeks. Fourteen weeks down the line, he called and asked why I chose to discontinue the course. I lost my money and learnt a lesson along the way as well. Don’t trust anybody who swears by God.

More fodder for the atheist in me. I took great pleasure in showing him my middle finger.

People close to me often accuse me of not being human enough. Because humans use intuition, discretion and experience to exercise choices. I use software and hardware to find my way through. Does that make me a cyborg? I think not.

As Rene Descartes, the French philosopher wrote in his Meditations: I will suppose, then, that everything I see is fictitious. I will believe that my memory tells me nothing but lies. I have no senses. Body, shape, extension, movement and place are illusions. So what remains true? Perhaps just the one fact that nothing is certain.

The author is Managing Editor of Forbes India, published by the Network18 group

About The Author

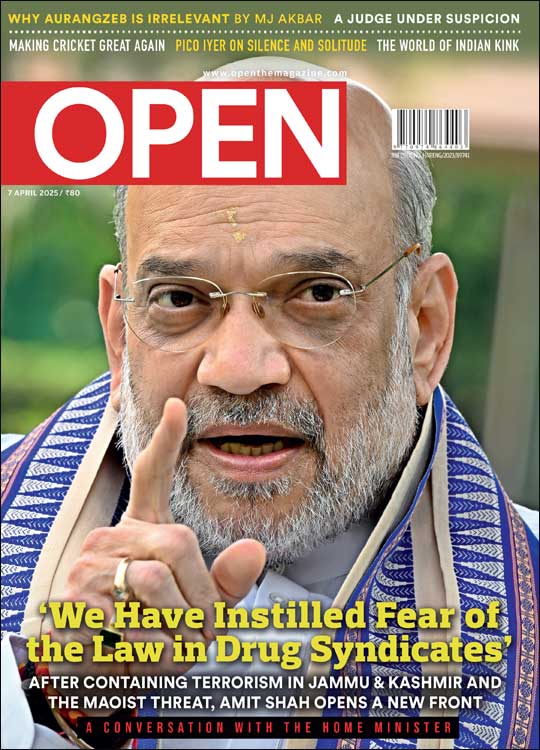

CURRENT ISSUE

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

The Hunger Cure V Shoba

BJP allies redefine “secular” politics with Waqf vote Rajeev Deshpande

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP