How Georgia Did It

Eight years ago, faced with rampant corruption, Georgia took a series of drastic steps, among them the overnight sacking of the entire police force. Did it work?

Samantha de Bendern

Samantha de Bendern

Samantha de Bendern

|

23 Feb, 2012

Samantha de Bendern

|

23 Feb, 2012

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/georgia.jpg)

Eight years ago, faced with rampant corruption, Georgia took a series of drastic steps, among them the overnight sacking of the entire police force. Did it work?

It was a warm summer evening last July, and I was sitting on the roof terrace of a smart restaurant in the Georgian capital Tbilisi, waiting for my old friend Giorgi, whom I had not seen for ten years. As the sounds of the vibrant city below drifted up, and the 13th Century church that dominates Tbilisi’s skyline soaked up the last rays of the setting sun, I could not but marvel at how much this place had changed since my last visit. The city was clean and bright, traffic flowed effortlessly along tree-lined boulevards and a brand new bridge, built of glass and steel, across the Mtkvari river that meanders through the town, lit up as dusk began to fall. It reminded me of the large glass building I had spotted on the road from the airport, completely illuminated from without and within in the middle of the night. According to my taxi driver, this was the new Interior Ministry, and it had been built of glass to symbolise the transparency of new state institutions.

Was I really in Georgia? Or did things feel different because of the soft evening light and a few cosmetic changes masterminded by the new government’s clever public relations strategists?

My first visit to Georgia had been in the winter of 1999. At the time, I was a NATO Civilian Officer from the International Staff in Brussels, and I was responsible for NATO’s public affairs programme in Russia and the former Soviet Union. Some of my work involved helping the newly independent states of the ex-USSR devise and implement political and security related reforms, and I was in Georgia as a guest speaker at an international conference focusing on the importance of fighting corruption. I remember being struck by how dark everything was: the streets, the houses, even the large public buildings.

Urban darkness was something that Europeans of my generation, even my parents’ generation, had never known, except perhaps those old enough to remember the blackouts during the air raids of World War II.

The heart of all this darkness lay in the rampant corruption that was paralysing power supply and just about everything else in Georgia in the late 1990s. Indeed, without resorting to bribery, ordinary citizens could no more obtain a power connection than function in any other walk of life. Bribes were needed to obtain passports, build a house, register a business or property, even access a hospital. But the bribes that were paid rarely ensured actual delivery of the service paid for, because none of this money was going to the state. Hence the darkness. Roads were catastrophically dangerous because most people bought their driving licences without having to demonstrate an ability to drive. Georgia’s universities were filled with those rich enough to pay entrance bribes, and the country’s graduates were those with enough money left over to pay for decent marks in the final exams. Money was paid to not pay government taxes or keep tax inspectors from issuing artificial fines. Public health inspectors would arbitrarily close businesses that did not pay bribes and turn a blind eye to those who paid, often with disastrous results overall in terms of public sanitation.

Some state officials not only managed to survive, thanks to bribes extorted from ordinary citizens, but amassed significant fortunes—in testimony stood the large mansions they had built on the outskirts of Tbilisi. Meanwhile, the treasury was empty, and the state had more or less ceased to function.

Two years later, Georgia was a fractured state that had hit rock bottom. The economy was in ruins, many areas of the country had less than seven hours of power a day, and crime and corruption were considered among the worst in the Soviet Union’s successor states. The tilting point came in November 2003, when, after fraudulent parliamentary elections, crowds took to the streets brandishing roses—hence the name Rose Revolution—demanding an end to corruption and the resignation of President Eduard Shevardnadze. He eventually resigned, and after fresh elections early in 2004, a new president and parliament were elected, with a strong popular mandate to eradicate corruption with whatever means possible.

The results of the reform measures were spectacular. While Georgia still scored only 2 out of 10 on Transparency International’s Global Corruption Index in 2004, the country showed the biggest change worldwide on the same entity’s Global Corruption Barometer, a yardstick that tracks public perceptions of corruption in 183 countries: only 4 per cent of the population surveyed expected corruption to increase, compared to 55.2 per cent in 2003.

In 2011, with a score of 4.1, Georgia ranked 64th among 183 countries on the Corruption Perceptions Index, a leap from 124th out of 133 countries in 2003. This puts it ahead of such EU countries as Slovakia, Italy and Greece, and well ahead of India, which ranks 95 with a score of 3.1. (Note: because of changes in the number of countries surveyed over the years, the best way to show the changes would be to show the shift in relative rank: in 2003, Georgia’s reputation was worse than 93 per cent of all countries surveyed; in 2004, worse than 91 per cent; and in 2011, just 35 per cent.)

As I sat on the terrace, sipping some delicious Georgian wine, I wondered how all this had been possible. I had read about the sweeping reforms brought in by President Saakashvili and his team, but nothing had prepared me for the modern, clean, safe city that I had encountered on my arrival, nor the infectious pride and enthusiasm over the changes in Georgia expressed by so many of the people I had met so far, from taxi drivers to foreign diplomats and think-tank professors.

My thoughts were interrupted when Giorgi’s aide arrived and apologised for his boss’ late arrival. I started to get a bit nervous, realising all of a sudden that I was not about to have dinner with an old friend, but one of the most senior politicians in the country. Would he have changed as much as Georgia had? When we had first met, he was a Member of Parliament, and I, a NATO official. But things had changed a lot since then. While I had quit officialdom for the anonymity and freedom of civilian life, Giorgi on the other hand had become interior minister, defence minister and was now deputy prime minister. Perhaps it would be more appropriate not to think of him as Giorgi anymore, but as Minister Giorgi Baramidze.

There was some activity near the restaurant’s entrance, and the atmosphere grew slightly tense as the guests fell silent and looked up from their plates. In walked Deputy Prime Minister Giorgi Baramidze, state minister for Euro-Atlantic integration, his imposing frame impossible to miss, still youthful face beaming a large smile and hand stretched out in welcome. He had hardly changed.

After we had sat down, exchanged some small talk and ordered some food, I asked him how all this change had been possible. My host laughed and admitted that it had been hard work, exhausting, stressful, strenuous, and was far from finished. He explained that in 2004 after the revolution, the new government knew that it had very little time and had to act fast. President Mikhail Saakashvili had been elected with a preposterous 96 per cent of the vote, something that would normally seem impossible in a democracy, and his United National Movement had 68 per cent of all seats in parliament.

They had been elected on an anti-corruption platform and had no excuse not to act. They therefore decided to undertake dramatic steps, and attack many different fronts at once: the civil service, tax police, power distribution system, education, customs… everything.

Baramidze then added that the reformers knew that they needed to send a strong message and present a strong symbol so that the people knew they meant business. They found this symbol in the traffic police, who were hated as much for the daily bribes they would extort from motorists as well as for their Soviet-style uniforms and behaviour, a constant reminder of Georgia’s pre-independence era. They were widely perceived as being the most corrupt of all state agents, and a position as a traffic policeman (in fact, in the whole police force) was so lucrative that applicants were willing to purchase it in the knowledge that the initial investment would be paid off with bribe money. According to a World Bank report, the going rate to become a traffic policeman in 2003 was between $2,000 and $20,000, depending on the place of posting; border areas were particularly lucrative because of smuggling and the prevalence of illegal armed gangs crossing to and from Russia. (Note: a mid-level public sector salary at the time ranged from $10 to $20 per month.)

When he was interior minister, Giorgi Baramidze oversaw the drafting of legislation that eventually led to the overnight sacking of the entire traffic police force of 16,000 men on a single night in July 2004 (by that time, he had moved to the Defence Ministry). He explained that because the force was so rotten, “we needed to apply surgical treatment”. He argued that although there may well have been some honest traffic policemen, it would have taken too long to figure out who they were, so it was easier to just get rid of all of them in one stroke. Over the next few months, 80 per cent of the rest of the police force was sacked, and a new police force was put together from scratch, with young recruits who were better trained and better paid.

The old police were given two months’ salary cheques and amnesty for any corrupt activities they may have taken part in, in exchange for their peaceful departure. The older ones were also given their full pension. There were some demonstrations, but by and large, the old force left quietly to join the ranks of the unemployed or become night janitors and taxi drivers. Very few applied for posts in the new police force, knowing full well that their backgrounds would be investigated.

“So, what happened to the crime rate? Surely, in the interim period, while you were training the new police, it must have been a disaster?” I asked, imagining the potentially devastating effect that sacking practically the whole police force could have in a country as crime-ridden as Georgia was back then. Baramidze’s answer underlined the urgency of reform: “The police were part of the problem as they were hand in [glove] with organised crime on one hand, and totally incapable and unwilling to prevent or investigate petty crime on the other. Not only did we not see a rise in criminality, but rates actually went down.”

I discussed this A few days later with a popular talk show host, Mikhail Tavkhelidze, and he gave a similar answer, adding that in the case of the traffic police, it was simple: “In general, ordinary people do not want to kill themselves, so they drive sensibly whether or not there are rules to be enforced. The crazy ones with fast cars usually had the traffic police in their pocket anyway and did what they wanted, so the absence of traffic police changed nothing.”

Tavkhelidze also explained that organised crime had been a serious problem in Georgia since Soviet times, and the sacking of the old police force had served to snap ties between crime syndicates and the state, thereby weakening the criminal bosses. Moreover, new anti-mafia legislation was introduced, modelled on Italian anti-mafia laws and the US Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, and the frequently televised arrests of high-profile criminal bosses sent a strong message to crime syndicates that their days of ruling the country were over.

These statements are all supported by independent studies by the World Bank and European Commission, as also independent think-tanks from the US and Europe, even reports by usually sceptical and critical Russian commentators. On the long-term effects of Georgia’s police reforms, a survey by the European Commission in 2011 states that Tbilisi is now considered one the safest capitals on the European continent, in spite of the fact that the overall staffing of law enforcement agencies has gone down from about 63,000 in 2003 to 27,000 in 2011. Another study in 2011 by the World Bank and European Bank for Recontruction and Development shows that only 1 per cent of the country’s population report having paid bribes to the traffic police in the past year (compared to 7 per cent in some parts of the EU). Also, according to a Transparency International survey of 86 countries, the Georgian police force is one of the least corrupt in the world, beaten only by Finland.

The new government did not stop at the police. Simultaneous reforms were undertaken all over the civil service; the tax code was changed and simplified, and in practically every walk of life, old cumbersome regulations were scrapped and replaced by streamlined procedures.

Restoring power supply was also one of the main challenges of the new government. This was done by increasing revenues in two ways: firing and in some cases prosecuting and imprisoning corrupt officials at all levels, and increasing power tariffs. The government gambled that the political risk in continued power shortages was greater than the political risk of higher prices. The gamble paid off, and people turned out to be willing to pay more money that they knew would go into state coffers, in return for electricity they would actually get, as opposed to paying less for what ended up as hardly any electricity at all.

As Baramidze explained to me in a recent phone call in preparation for this article, in order to consolidate the reforms, the government realised that along with cleaning up corrupt state agencies, it was important to reduce as much as possible the opportunity for future corruption. This was done by minimising the points of contact between citizens and state officials, and simplifying the cumbersome acts of everyday life that both citizens and officials would expedite by resorting to bribery: the issuance of permits, the stamping of documents, the innumerable bureaucratic hurdles that one had to cross in order to obtain authorisation to build a house, open a business, drive a car.

A World Bank report released in February 2012, called ‘Fighting Corruption in Public Services, Chronicling Georgia’s Reforms’, details these measures: between 2003 and 2011, the number of permits and licences required to set up or run a business was reduced from 909 to 137. The number of procedures to obtain a construction permit went down to 9 from 25. The number of import tariffs was cut from 16 to 3. The simplification of the tax code, the reduction of the number of taxes (from 22 to 5), lowering of tax rates and the introduction of electronic filing of tax returns not only reduced the role of the notoriously corrupt tax police, but increased the collection of taxes. As a result, the tax base went from 80,000 taxpayers in 2003 to 225,000 in 2010, out of a population of 4.4 million, and taxes that made up 12 per cent of the state budget in 2003 made up 25 per cent in 2011.

In order to ensure the passing and implementation of reforms, the government also managed to get rid of time consuming consultative committees and lengthy approval processes, streamlining decision making procedures as far as possible. In any case, with an overwhelming pro-government majority in parliament, lengthy debates and opposition were more or less non-existent.

A factor that made the fight against corruption so successful in Georgia was also the introduction of a zero-tolerance policy for bribery, and imprisonment upon conviction. Although this has reaped positive results, it has also created a whole series of new problems: with all the corruption-related arrests that continue till this day, Georgia’s prisons are now bursting. The country has the fifth highest per capita prison population in the world, and with most cases brought before the courts leading to convictions, this population is growing. This is leading to demands from within Georgia as well as from the international community for rapid reform of the judiciary, which is widely perceived as lacking both independence and professionalism.

Insofar as petty and mid-level corruption is concerned, the results still hold nearly eight years on. Eka Gigauri, director of Transparency International’s Georgia office, confirmed this in a recent discussion, and this opinion has been borne out by countless studies by international organisations. The economy, while not booming, has also made a remarkable recovery and the business climate is recognisably better.

Georgia now ranks 16th in an International Finance Corporation study on ‘ease of business’ among 163 countries, and GDP per capita as well as overall GDP are more than twice what they were in 2004. However, Transparency International, opposition politicians and academic experts from inside and outside Georgia concur that ‘high level’ corruption persists. In Ms Gigauri’s words, “Corruption is not just about taking bribes, it is also about the misuse of power by elected officials.” Transparency’s assessment of the current state of affairs is that the main institutional barriers to further containing corruption arise from a lack of independence of the judiciary and media, a weak civil society and lack of proper checks and balances. “When senior officials are prosecuted for a crime, they are rarely convicted because the judiciary is still far too dependent on the government,” says Gigauri. The public prosecutor is seen to exert considerable pressure on judges over rulings, the judiciary lacks financial independence, and legislation ensuring the lifetime appointment of judges is still to be implemented fully.

Popular sentiment around the judiciary also remains rather negative, as borne out in a report published in January 2012 by the Caucasus Research Resource Center and financed by USAID, which summarises a Georgia-wide survey on popular perceptions of the judiciary. The report shows that many in the country believe that judges are selected and appointed based on their willingness to toe the government’s line, and are reluctant to issue decisions that might go against the government’s interests.

As for the political opposition, according to Gigauri, they have a problem getting their message across because most media outlets are by and large owned or controlled by people related directly or indirectly to the state. The recent auction of Tbilisi’s television towers, which went to a single contender registered seven days before the auction took place, for example, raises worrying questions both about freedom of the media and potential high-level corruption.

Striking a balance between harnessing the will against corruption and ensuring that all stakeholders in politics and civil society are consulted and involved is a challenge in any democracy undergoing reforms. This is even more so if reforms are being undertaken in the midst of an economic breakdown, as was the case in Georgia in early 2004, and with large chunks of the territory spinning out of the Central government’s control.

Many (but not all) of these problems have been overcome, thanks to the nerve and will of President Saakashvili’s government. The upcoming parliamentary elections scheduled for October 2012 will also be a litmus test by which the international community will judge Georgia’s progress.

For many, the jury is still out. Thomas de Wall, a well-known specialist on the Caucasus region, is reported to have said at a conference organised by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in June 2011, that one of the problems he identified “is that the governing elite in Georgia, having come to power as the result of a peaceful revolution, is still thinking rather in revolutionary mode”.

As our dinner last July drew to a close, I asked Giorgi Baramidze whether he thought that the dramatic reforms undertaken in 2004 would have been possible without a revolution. “What made the reforms possible was our strong political will,” he replied, “and what gave us our political will was the strong popular support that came from the revolution—itself a manifestation of the fight against corruption. At the end of the day, it means that our will came from the popular support that we had, not just the revolution. It is important to remember that just as not all revolutions lead to change, you do not always need a revolution to implement change. It’s a question, well… of will power.”

When we said goodbye, I asked Giorgi what the one thing would be that could sum up his feelings about the way the present government had tackled corruption. He paused, and said simply: “We took a risk. But it was worth it.”

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

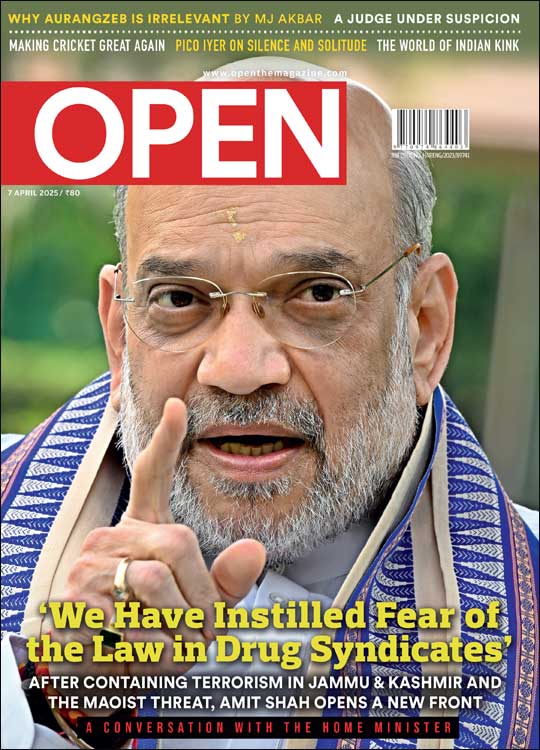

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

Why CSK Fans Are Angry With ‘Thala’ Dhoni Short Post

What’s Wrong With Brazil? Sudeep Paul

A Freebie With Limitations Madhavankutty Pillai