Kerala Loves Kim

The unlikely popularity of one South Korean filmmaker among Malayalee cinephiles

Shahina KK

Shahina KK

Shahina KK

|

25 Dec, 2013

Shahina KK

|

25 Dec, 2013

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/mal-poetry.jpg)

The unlikely popularity of one South Korean filmmaker among Malayalee cinephiles

Dear Kim,

I am one among the numerous fans you have around the world. I could be the only fan of yours who has not managed to see a single film of yours. I wonder if you have heard about Kerala, a South Indian state. You have a huge fan following here. Internationally acclaimed film makers like Adoor Gopalakrishnan and Shaji N Karun hail from this place. I write this from Illikkunnu, a faraway village in one of the hilly districts of Kerala. I have read a lot about you and your films through magazines and newspapers. I have read in newspapers that your films draw huge crowds at film festivals in Kerala. Film festivals are held in cities far away from our village. Even though it is expensive to go for film festivals, a group of us plan to attend one every year. But when the time comes, something or the other comes in the way of our plans. This is because, as daily wage labourers, our lives are tied to the fluctuating market prices of ginger and pepper. The audiences in the city are lucky. They get the opportunity to watch great movies. I write this to tell you that your films do not reach the villages. The same is the case with Indian art house films. This letter is not an attempt to find a solution to such issues. I write this because of the disappointment I feel in not being able to see a single film made by you. We have been trying to access at least the DVDs of your films. We could not find any. Dear Kim, I request you to kindly send me DVDs of some of your films. Kindly consider this as a plea by a village bred Kim Ki Duk fan.

Hoping that you are able to make many more great films,

Ajimon KS

Ajimon KS is not a real person. He is the protagonist of the 2009 short film Dear Kim, directed by Binukumar PP, which is about three youngsters living in a remote hilly village in Kerala making desperate attempts to watch the films of Korean director Kim Ki Duk, their favourite filmmaker. Their leisure time conversations are all about cinema, the French new wave, and directors like Godard, Abbas Kirostami, etcetera. They dream of film festivals happening in cities far away and plan to attend the International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) every year. But, as the letter says, it never happens for some reason or the other. Once, they manage to get hold of a DVD of Kim’s 1997 film Wild Animals through a friend who visits Chennai. To their disappointment, it turns out to be a porn movie wrapped in the cover of Wild Animals. Finally, they decide to write a letter to the filmmaker requesting him to send them a few DVDs of his films. They do not have either Kim’s address or email ID, and they hardly know how to send an email. The guy at the internet café, eager to get rid of the village folk who do not even know how to use a computer, deceives them and sends the email to a random address. The three fans, unaware that their message was never received by Kim, live in anticipation of a response from the filmmaker.

Youngsters like Ajimon are not a rare breed in Kerala. They are a product of the film society movement that swept across the state in the 1970s and 80s, through which people were exposed to classics, French New Wave and Russian art house cinema. Writings on the lives and work of Russian legends like Sergei Eisenstein and Andrei Tarkovsky, Italian masters like Federico Fellini and Pier Paolo Pasolini, and French stalwarts like Jean-Luc Godard and Alain Resnais were plentiful in Malayalam literary magazines. So though the story of Ajimon is fictional, there is an element of truth in it. You can find Kim Ki Duk fans in Kerala who have not even watched his movies.

The sensation was triggered in Kerala in 2005, the year the IFFK screened five of Kim’s films in the ‘retrospective’ category. His films—the acclaimed Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter…and Spring,3-Iron, Samaritan Girl, Bad Guy and The Coast Guard—with their enchanting beauty in each frame, their blend of mysticism, spirituality, erotic desire and unflinching violence, were a scintillating experience for the audience. In the years since, Kim’s films, such as The Bow, Time, Dream, Pieta and Moebius have been IFFK’s best crowd-pullers.

Many who express a serious passion for cinema have ceased to be Kim fans, saying his recent movies have been increasingly mediocre, and are embarrassed to see this phenomenon of overwhelming crazy love for Kim. Some critics suspect people are not really watching his films, just blindly adoring him.

The fandom around Kim Ki Duk is similar to that around superstars of popular Indian cinema. The filmmaker was terribly surprised at the way people embraced him in Kerala. A guest at the closing ceremony of the 18th IFFK in December, Kim witnessed in person the craze around his name among festival-goers. On the morning of 11 December, the day after his arrival at Thiruvananthapuram, Kim was swarmed by people on the street—probably festival delegates—for whom the sight of their most adored director was a great surprise. Many competed to take photos with him. (I too had one taken, though I don’t belong to the fan club.) A few heads peeped out of a passing KSRTC bus and shouted “Hello Kim Ki Duk!” Later, in an interview, Kim said he had never received such a welcome anywhere in the world, even in his own country. In Korea, he is one of the most controversial filmmakers for the amount of violence in his films. He has been called the ‘bad guy’ of Korean cinema, and has often been bashed for outrageous misogyny in his films.

“Last January, I was invited to deliver a talk on Korean cinema and the Malayalam new wave at the Korean Cultural Centre in Delhi,” says Bindu M, a film scholar and teacher at Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi. The discussion, followed by a screening of the short film Dear Kim, aroused immense curiosity and surprise among the audience. “During the tea [after the screening], the Korean Center director expressed his surprise to me in definite terms. He said, ‘Why is it that Keralites like Kim Ki Duk so much? His films are thought to be very violent in Korea and we have other art cinema directors too.’”

What can we make of this strange moment of overwhelming, hysterical, hyperbolic fandom for Kim Ki Duk? Bindu is unsurprised. She thinks the root of this phenomenon lies in the strong desire for art house cinema that has existed in Kerala since the 1950s. “But there is something else that is transpiring in the Kim Ki Duk fandom. While clearly belonging to the domain of art cinema, Kim Ki Duk, as many have pointed out, explores the spiritual and materialist, the moral and amoral, the city and the rural. Leitmotifs of Buddhist religious practices are often obvious in his films. To me, the Malayalee cinephilia for art cinema and the quest for parallel modernities find their place in Kim Ki Duk.”

There are many ‘Kim jokes’ that do the rounds among film lovers in Kerala. One is about a group of Kim fans who go to Korea to meet the director in person, but fail to find his house, as nobody in Korea knows where he lives. The group is tired and disillusioned and about to return without meeting the director when, finally, they find a house bearing a signboard that says: ‘Beena Paul Venugopal has blessed this house’. No further confirmation is needed; they understand that Kim lives there.

The joke plays on the signboards often seen outside Catholic homes in Kerala—‘Jesus Christ has blessed this house’—but to really understand the humour, you’d have to know who Beena Paul Venugopal is. She has been the art director and curator of IFFK over a decade and is a National Award-winning film editor. The joke implies it was she who made Kim Ki Duk a phenomenon in and around the country. “For God’s sake, please believe me, I am not responsible for this frenzy of love for Kim,” says Beena. “I met him for the first time when I went to Korea for an international editing workshop a couple of months [ago]. He was staying in the same hotel [as I was]. I met him in the lobby and invited him to Kerala for the 18th International Film Festival. He could hardly follow English and only understood the word ‘Kerala’. He was very happy to hear the very name of our state and later his translator agreed to come to Kerala for IFFK.”

Film scholar C S Venkiteswaran has an interesting theory to explain Kim’s popularity: “For the Malayalee male youth, whose tunnel lives are severely limited by omnipresent surveillance by an ageing population and a highly moralistic society, Kim Ki Duk offers a free world of amorality. In his films, they are free to experience and explore the potential contours of all their pent up [impulses] without any moralistic or social hindrances. More importantly, Kim Ki Duk’s is an extremely ambivalent world; it is not just misogyny, violence, lust and power that they pursue to their extremes, but also silence, stillness, spirituality, tenderness, love and care. Maybe it is this dizzying oscillation between these luring extremes that fuels the irresistible fascination for Kim’s films.”

Venkiteswaran keeps himself away from the deluge of love for Kim. He loves some of his early films, but not the recent ones. “I find his recent films a little morbid to my taste, for one has seen many of these themes being dealt with in a much more sensitive, deeply humane yet incisive manner by the likes of Im Kwon-Taek and Bae Yong-Kyun, etcetera.”

“I don’t mind [being] called a Kim fan,” says Praveen SR, a journalist who has watched most of Kim’s films. “I would rate him among the best in the business for his mastery over the craft, [and] also for pushing the limits in what can be shown on screen and using it as a [mode] of social commentary.” As far as Praveen is concerned, it is a surprise that Malayalees who frown upon even the slightest immorality on screen stand up and cheer for Kim Ki Duk’s films, where morality is in short supply.

“There surely is an element of hype behind the hysteria witnessed this time during his visit and the screening of his latest film. There was scant media attention towards Carlos Saura or Marco Bellocchio, who are equally or even more renowned filmmakers as Kim.” But despite the hype element, Praveen thinks a sizeable chunk of the audience is truly fascinated by Kim’s craft and the way he uses it to disturb and move viewers. For those living in a society known for its repressed sexuality, watching an expression of violent passion on screen as part of a packed audience might at least provide a false sense of breaking shackles.

Many seasoned film lovers rate Kim as mediocre. His films are simple and not hard to understand; they do not offer anything very complex. Kim tells universal stories of love, passion, violence and marginalisation, betraying hardly any clues about the cultural context of the story being told.

“Most Kim Ki Duk films are either visually pleasing or thematically provocative. They are mostly simple narratives that do not demand much training in understanding cinema,” says Roby Kurian, a Malayalee living in the United States who has a passion for cinema.

KR Manoj, a young film maker and winner of this year’s FIPRESCI award for the best Malayalam cinema for his film Kanyaka Talkies, points to the mix of erotic content, violence and misogyny iced with Buddhist spirituality to explain what makes Kim’s cinema gel with the Malayalee audience. During the screening of his latest film Moebius—an outrageously violent film, featuring castration, rape and incest—at this year’s IFFK, two or three delegates fainted and had to be taken to hospital. Yet the hall was packed and had rung with applause at the end of the film. It seems that the critics of this crazy love for Kim are right: Malayalees love to watch whatever they pretend to oppose.

I retired from watching Kim’s films after a screening of his 2012 feature Pieta at last year’s IFFK. The violence and misogyny in it were too much to bear. When I met him on the road last week in Thiruvananthapuram, wearing a black jacket and trousers with the humblest smile I had ever seen, it was hard to believe he was the same Kim, the ‘bad guy’ notorious in South Korea for his arrogance both in cinema and life. “Why this kolaveri (desire to kill) toward women?’ I wanted to ask him. I could not, for two reasons. First, because he hardly follows English and I would have been unable to make him understand what I wanted to ask. And second, by the time he stopped to pose for a photograph with me, he was surrounded by a group of fans.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

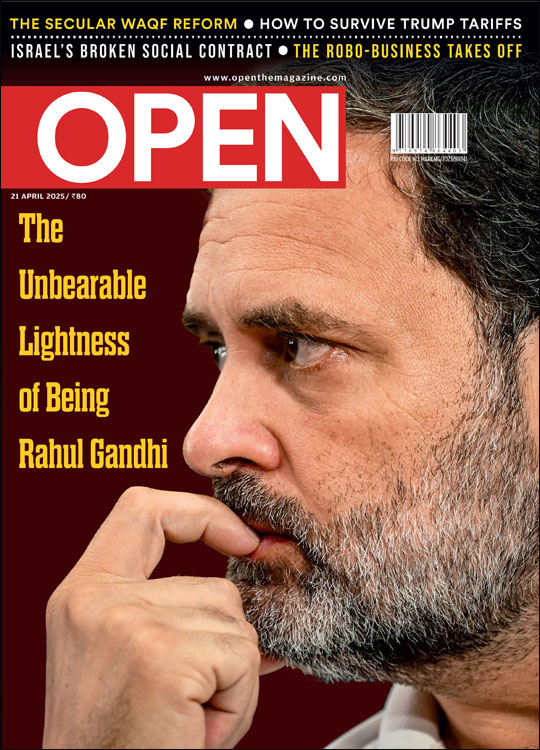

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Rahul Gandhi

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

The Gifted Heir Open

GALGOTIAS UNIVERSITY Open Avenues

A Failing Vote Bank Rajeev Deshpande