Life & Letters

My Friend Guru

Upon a chance meeting, a first-time hero and an assistant director made a lofty promise to each other. That promise culminated in a noir-styled movie, Baazi, in 1951. Its inimitable hero, Dev Anand, remembers his troubled and only true friend Guru Dutt

Dev Anand

Dev Anand

Dev Anand

31 May, 2011

Dev Anand

31 May, 2011

Dev Anand remembers his troubled and only true friend Guru Dutt

In 1946, I was on the payroll of Prabhat Film Company and was playing the lead in my first film, Hum Ek Hain. One day, as I was walking out of the studio, I saw a young man of about my age entering, and we exchanged polite hellos. “Are you doing the main role in the picture?” he asked, and I replied, “Yes.” He offered me his hand. “Well, my name is Guru Dutt and I’m an assistant director. Great to meet you. I hope to see you here more often,” he said. He gave me a beautiful smile and started to leave. A few seconds later, he turned and stared at my shirt. I looked at his. I realised he was wearing my shirt and I was wearing his. Obviously, the washerman had interchanged them. We had a hearty laugh and embraced each other. We were to be friends for all times.

That was how I first met Guru. We promised each other that the day I became a producer, I’d take him on as a director, and the day he directed a film, he’d cast me as a hero. And I’m not a promise breaker. I did launch Guru as a director in Navketan’s Baazi in 1951. He even appears in the beginning of the film.

Nobody’s ever known Guru better than me. He would travel by buses and trains to pick me up from my home in Pali Hill and take me to his place in Matunga. His mother would take us into her kitchen, make chapattis and serve us food. Often, he’d bring his camera with him and photograph me in Pali Hill, at a gold club that doesn’t exist anymore. Guru was fond of taking pictures, of making pictures. He was hardworking and intelligent. Later, I discovered he was also fond of acting. But I don’t think he was a great actor. He was a better director. He used to waste a lot of footage.

We had different personalities, but connected in many ways. He suffered from melancholia. He was a good man, a good thinker, but a back bencher. He never wanted to be part of a crowd. He was shy, but good at his work. However, he couldn’t take failure. Look, everybody meets with success, but you also face failure. Not every film is a masterpiece, not every film is a hit. But a film from a good maker is a good film. The day he realised his film was not a hit, he could never make one again. The day he realised that his Kaagaz Ke Phool did not do well—he’d gone to Delhi to open it in the presence of President S Radhakrishnan—he was a sad man. He never went behind the camera to direct; he only acted. He took Abrar (Alvi), but never had the courage to direct. Woh cheez khatam ho gayi thhi. (Something in him had died.) But you’ve got to be strong—unless you are strong, you cannot live in this world. Woh weakness thhi uski. (That was his weakness.)

He made sad pictures. People call some of his films classics today—mostly, Kaagaz Ke Phool and Pyaasa. But at that point, nobody liked them. It was later that a wave began and people started admiring his work. Who would believe that those films were made by a director in his mid 30s?

I’ve done more films with my brother Goldie (Vijay Anand) than Guru. They were different directors in every possible way. I’d say Goldie was more dynamic, but Guru had his own style. I did only three films with Guru: Baazi and Jaal ; as you’d know, CID was only produced by him. Today, I miss Goldie as a great director who handled me well, and Guru as a great comrade, a dear friend of my age with whom I could laugh and share jokes. When I had my love affair with Suraiya, I was closer to Guru than anyone else.

I remember Guru and I watched the Italian film Bitter Rice (1949) at Excelsior theatre and he was so impressed that he decided to use it as an inspiration for Jaal (1952). He asked me, “Dev, will you be my villain?” I said, “Karunga bhai, karunga. (Of course, I will.) As long as my role is central.”

I’m saying this for the first time but Baazi was conceptualised after Gilda, Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford’s 1946 film. Those days, Balraj Sahni had just returned from the BBC as a commentator and he needed a job. He was a good writer and I brought him and Guru together. They were looking for a script and finally took the idea for Baazi from Gilda. We were surprised to find that the ‘good boy on the wrong side of the law’ subject could work so well. The film was a huge hit. I went to Ahmedabad, and hundreds and hundreds of boys and girls ran after my car. While I wouldn’t say I tasted stardom for the first time with Baazi—I had experienced fan frenzy in Ziddi (1948) before—it did make me a huge star.

And it launched many careers. Sahir Ludhianvi became famous for his lyrics. He was a great poet who could express feelings simply. Uske alfaaz chubhte thhe. (His words would pierce.) Then, my brother Chetan brought Kalpana Kartik, who would later become my wife, from St Bede’s College, Shimla. It was her first film, and when it became a hit, I wrote to her saying, ‘Baazi has clicked.’ (Laughs out aloud) And she innocently asked me, “What does clicking mean?” Johnny Walker used to hang around the sets trying to get noticed, and we did notice him. We all loved him, gave him his first chance and he remained a friend throughout. And, of course, SD Burman, whose music for Baazi is still remembered. When I went to Jodhpur, a distributor told me that pilots from the nearby Air Force station would come into the theatre every time the song Tadbeer se Bigdi played.

So many people came into my life, but Guru and I shared something different. Our journey began together. I’ve always said he was my only friend and I repeat that today because jab Dev Anand star ban gaya toh phir kaun sachcha dost banta hai? (After one becomes a star, how does one really make true friends?)

In the last days of his life, he called me and said he’d love to have me over. I saw the man then, he’d lost his hair and was weak. He was suffering. He was not the same Guru I’d known. We discussed making a film together. I told him, “Look, why don’t you write a great script? Let’s do it.” This was three days before he died. When I heard of his death, I went straight to his home. I was the first man to go into his room. His dead body was lying there. There was a glass of blue liquid on the floor. He was sallow. And dead.

(Takes off his reading glasses and bends forward) When I first met him, mujhe aisa lagaa ki bohut lambi daud daundenge hum saath mein, par woh apne mein kaheen kho gaya. (I thought we would live and run together for a long time, but he lost himself within somewhere.) He should have made more films. He had so much in him. Thirty-nine is not an age to die.

The image I want to keep of him is not of that Guru, but of the Guru with whom I shared the most special friendship of my life. Zindagi ki daud mein uske jaisa dost phir kabhi nahin mila. (In life’s run, I never found a friend quite like him.)

As told to Shaikh Ayaz

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/cinema-devanand.jpg)

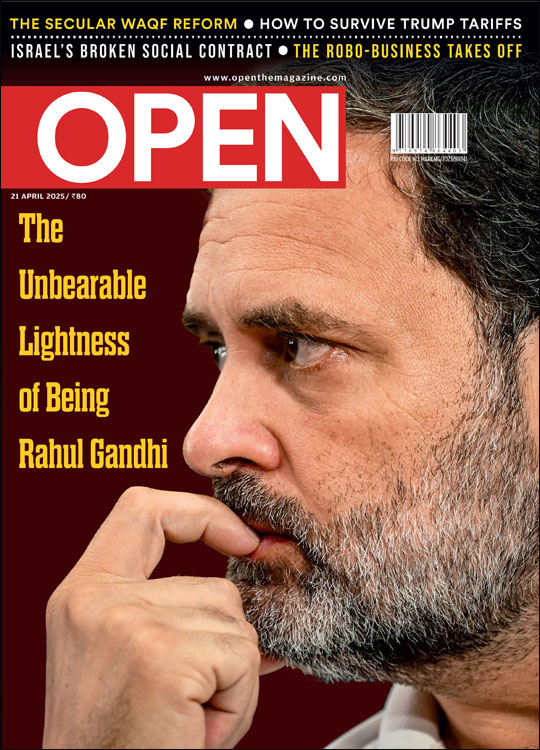

/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Cover-Congress.jpg)

More Columns

Maoist eco-system pitch for talks a false flag Siddharth Singh

AI powered deep fakes pose major cyber threat Rajeev Deshpande

Mario Vargas Llosa, the colossus of the Latin American novel Ullekh NP