Even Gods Must Die

Like children listening to tales of kings and queens, my sister and I would listen wide-eyed to stories of Panditji who sang with great relish and complete abandon.

I find it horribly difficult to deal with the passage of time and the inevitable cyclical changes it brings with it. This may strike many people as being a strange statement, coming as it does from someone who has spent the past three decades or so studying music, and who should by now have learnt to keep time. But this isn't about wishing away the wrinkles, sagging jawline, swollen ankles, doddering knees, or the many ailments considered the inevitable companions of age. It has to do with my severe deficiency in accepting that even those who for years we have known to be indefatigable, indomitable and unconquerable must one day bow to the inevitable as we watch helplessly. Even our gods have to die. That's the reality I have trouble facing.

Remember the first time you noticed either of your parents stoop a little, or start to slow down a bit? And remember how you tried to brush aside the thought that they have started ageing, and tried desperately to will yourself into believing that they are fine and will be fine forever more? The fear of the inevitable and its chilling finality is what I am getting at.

My sister Ragini and I were brought up on music, so to speak, and from as far back as I can remember coherently, one of the magnificent Indian voices we heard, and learned to love and respect dearly and deeply, was the voice of Bhimsen Joshi. In small town Allahabad, where we grew up, the arrival and performance of great artistes was nothing short of a major event, for which the town geared up in a way that is now reserved only for film stars and celebrity cricketers. Back then, reception committees were formed, tasks assigned to committee members, wars waged on who would felicitate the visiting celebrity, colourful badges in garish satin pinned on to lapels with rusty little safety pins, and the others expected to turn out in their Sunday best. For a Bhimsen Joshi concert, we were spurred on by our parents and teachers to prepare diligently for the annual music competitions that took place at the Prayag Sangeet Samiti, where victory meant a shiny cup or trophy, a certificate, and a place on one or the other side of the wings of the stage, from which vantage point the winners could watch and hear the greats of Hindustani music perform every night.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

That's where I first heard him. The man whose voice had so often made my agnostic father weep in response to his Jo bhaje Hari ko sada. Dad had told us about the flamboyant style of the Pandit, his wild gestures and mannerisms. We had listened in awe, much like children listen to stories of great kings and queens, flying saucers and great birds with wingspans larger than airplanes. We had heard, with amazement, that the Pandit always sang with an abandon that was his hallmark, and without a care for microphones, swaying wildly and gesticulating as he swept his head from side to side in an imaginary arc. We were told about the clever someone who decided to record the maestro and prepared for the historic event by seating him behind a semi-circular arrangement of microphones, meant to catch every note the Pandit sang in any direction. But what do you know? Just when the clever someone was beginning to feel smug about having found a solution to the maestro's unpredictable movements, he swivelled and swung to look straight at the tanpura player seated behind him, volleying a breathtakingly long taan at the poor soul, defying any mike placed anywhere near him. And now, seated among a gaggle of 'pryje-weeners', as we were called by the Sangeet Samiti staff, we would have the privilege of hearing him sing live only a few feet away from where we sat barricaded behind a plywood railing with a lacy jaali pattern.

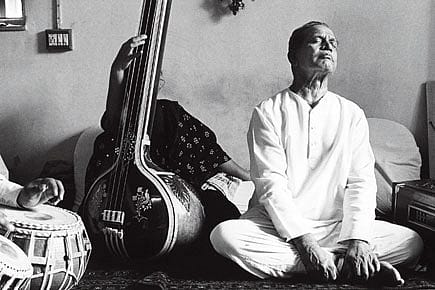

What are the memories of Pandit Bhimsen Joshi and his music that stay etched in my mind from those first few times that I heard him in Allahabad? Without doubt, the persona and charisma of a performer leave an indelible impact on listeners. And therefore, the wild eyes, distended and gaping ahead in an unseeing gaze; the gaping mouth stretched in a grotesque grimace; the expressive hands now sweeping and brushing up bunches of swars, now picking them out of the sky, weaving them into little clusters and tossing them up in the air again. The entire spectacle was nothing short of memorable. But more so because of the sound of the music it accompanied. Without the music, try the gesticulating and head swinging, mimic the mannerisms—as so many of his followers and disciples have done to their detriment—and all you'll get is a gaggle of onlookers giggling at your antics instead of the cult following for the music of Bhimsen Joshi.

Powerful and sure, bold but fluid like calligraphic strokes, his voice interpreted ragas with such clarity that even rank beginners were able to identify them, exchanging looks silently as they recognised a Shuddha Kalyan or Puriya or Todi. But it was Bhimsen Joshi's Todi, Puriya and Shuddha Kalyan that you went home with, that played in your head repeatedly, long hours after the concert was over. Let's also be clear about this: you didn't go to a Bhimsen Joshi recital for a textbook interpretation of a raga. It's for the many deviations, the forays away from conventional interpretation that you waited for, the explorations with which he almost invariably delighted his listeners. I don't know if I am explaining this quite the way it should be explained, but all notable classical musicians work towards establishing a style they can call their own, even though it is reminiscent of deep-rooted traditions and gharana associations. Having once established an individual style, it is equally important to remain tethered to it, and yet be able to avoid the danger of becoming repetitive and predictable.

So how did Bhimsen Joshi manage all this? He was prone to singing the same ragas in most performances, often repeating the same bandish. When everyone around him was busy publishing books of their own compositions and organising book launches, he preferred to sing the same time-tested compositions—Langar kaankariya jin maaro in Todi, Tadpat rainaa dinaa in Maru Bihaag, Ras begi begi aavo in Shuddha Kalyan, to mention just a few signature Bhimsen Joshi pieces. What then makes the listeners hang on to every swar he sings? It is possibly that strange alchemy of taaleem (rigorous study) and taaseer (the gift of being able to touch hearts), the combination of hours of gruelling riyaaz mixed with a determination and passion for the music that defies formulaic stereotypes.

If will and determination contribute to the making of a one-of-a-kind musician, then there was none better than Bhimsen Joshi to prove that. My colleague and gurubhai Sudhir Nayak, who has been fortunate enough to have accompanied Bhimsenji on the harmonium for several years, and has had the opportunity to follow the legendary singer closely, has many anecdotes of his superhuman will power—tales we still listen to with child-like incredulity. These are stories of his infamous trysts with alcohol, when he would drink himself red-eyed and incoherent, and then insist on driving at manic speeds to concerts hundreds of miles away, zipping down highways at great speed, often on the wrong side of the road, in imminent danger of head-on collisions. Having reached his destination, miraculously without injury to his person or vehicle, but with his long suffering co-passenger in a fear-induced comatose state, he would ask for an unusual antidote to his inebriated condition— a plate piled high with green chillies. He would grab them off the plate, stuff them into his mouth, and proceed to chomp on them before he went on stage and sang a concert with the same concentration and intensity that others reserve for worship or meditation!

It is strongly recommended that readers battling the bottle refrain from trying out Panditji's antidote without having qualified medical assistance at hand.

Some years ago, a bout of severe ill health and surgery forced Pandit Bhimsen Joshi into temporary retirement. Mere mortals might have drifted resignedly towards permanent retirement, but Pandit Bhimsen Joshi recovered and was soon back on the concert stage, albeit unable now to stride fearlessly on stage or sit cross-legged. I was present at one such concert in Mumbai, and it broke my heart to see him being helped onto the stage, unable to walk without the support of his disciples. I had been eager to hear him sing again, but now I wanted to shut out the sight of an ageing and infirm Panditji. It was even more unsettling to see him sit on the edge of the dais, one hand clenching and unclenching uncontrollably. I should have known better than to doubt his strength and ability to transcend even age and illness. He started the concert with Raga Maru Bihag, the powerful steel-edged voice still easily recognisable, though a little hoarse and quavering for the first few minutes. The two younger disciples providing vocal support were quick to come to his aid, but soon the sinewy tensile voice that music lovers adore was in its element again, and the voices of the two younger men began to appear far more feeble, weary and ragged than the guru's. The magic was back in the music and I just sat and listened, marvelling at his sheer mastery, and the easy familiarity with which he traversed raga and taal. Not just an easy familiarity, but an intimacy with the idiom that comes from endless hours of riyaaz, of repeating the same phrases tirelessly, of hearing yourself over and over again, till you find your true voice. Is that why he preferred to sing the same ragas and compositions repeatedly, I asked myself, to get to the point of internalisation where you don't have to count the matras, but just burst into song knowing it will be right? I don't really know because I never got the chance to ask him, and even if I had, I doubt he would have given me an answer. I guess we must learn from even his silence and reticence. Perhaps it suggests that we must each search for our own answers, and if at all we discover answers anywhere, it would be in the hours, days, years—a lifetime spent in loving and learning music.