Prisoners of a Dream

Portraits of life imitating old Bollywood in the streets of India

Chinki Sinha

Chinki Sinha

Chinki Sinha

|

04 Oct, 2012

Chinki Sinha

|

04 Oct, 2012

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/bolly-1.jpg)

Portraits of life imitating old Bollywood in the streets of India

DELHI, BOMBAY ~ What should a boy like him do with himself? He’s got a shard of mirror, a little comb and a memory brimful of notes from sitting in a dark theatre damp with years of neglect. Imperial cinema in Paharganj. A red decrepit building that plays movies from the 1980s and 1990s. This is where they come, the street kids. To whistle, clap and dance. He is one of them, but he is no longer a child. He can hold his breath and stammer like SRK. Or deliver filmi lines with just the right affect. Like this one from Ready, a Salman Khan film: “Zindagi Mein Teen Cheez Kabhi Underestimate Mat Karna—I, ME & Myself.” A few weeks ago, he stood shouting “maar sale ko, maar” as Suniel Shetty beat up the villain in Krishna. Bollywood for them is anchor, teacher, escape—the elsewhere realm.

But not the Bollywood of today. Shekhar had gone to watch the recent Imran Khan starrer, Jaane Tu Ya Jaane Na, but he couldn’t sit through it. This was not his world, not the staple he had grown up on, it had none of the underdog-who-finally-made-it pull, a la Muqaddar Ka Sikandar or Deewar, both Amitabh Bachchan starrers. The rejection is mutual. Not only have these narratives gone out of Bollywood scripts, the multiplex theatres of today have no room for these kids. Understandably, their favourite haunts are theatres like Imperial and Sheila in Delhi’s Paharganj area or Gulshan Talkies and Silver Talkies in Bombay’s Pila Haus neighbourhood, which re-run the underdog movies of the eighties and nineties that sustain the dreams of these kids.

Twelve years after he ran away from Kalyanpur village in Bihar’s Munger district, Shekhar Sahni is still on the streets, figuring his way out.

At 24, Shekhar is a bit jaded. He is lean and dark and short. He has sunken eyes, hollow cheeks. Yet, his eyes burn bright. “If nobody will give me a chance in Bollywood, I will give myself a chance,” he says. “I used to say this when I was a tour guide with the Salaam Baalak Trust. I still believe in it.” In the world of Bollywood, “anything is possible. It is a magical world,” he says. Back in the day when he was attending NSD’s (National School of Drama) summer school, he carried a tube of Fair & Lovely in his pocket, and would rub it on his face through the day. They said he would make a great actor.

It didn’t start in NSD, the obsession with acting. The first film he watched at a theatre was Salman Khan-starrer Hum Aapke Hai Kaun. He and friend Javed got on a train to get to the nearest town, Sultanganj, where the film was running. Later, when he came to Delhi as a runaway child, he spotted a tattoo artist at a market, and got Prem, Salman Khan’s favourite screen name, etched on his arms. Later, when he turned into an SRK fan, he’d wear full-sleeved shirts to hide the tattoo. Before Salman, there was Ajay Devgan, whose 1991 debut film, Phool Aur Kaante, Shekhar watched on Doordarshan. He started styling his hair after Devgan, parting it on the extreme left. On Saturdays, when his schoolteacher Sharmaji would ask him to sing for the antakshari class, he’d go full throttle: “Maine pyar tumhi se kiya hai… .” Hand on his heart (to the right of the chest, Bollywood style), he’d sing for the girls in class too.

Drugs have wrecked his body. But he still has a plan to redeem himself. With the little money saved from his delivery boy job, he wants to go to Goa, work there in the holiday season, and study tourism management. When he is not so desperately poor, he will act again.

If Bollywood won’t give him a chance, he will make his own film.

He ran away from a happy home in pursuit of the magic of Bollywood. Like so many others before him, he too fell through the cracks.

Aakash, ‘Dedh Footiya’ to his friends, stands up, awkwardly eyeing the others gathered around him, rushes inside the tin shed, emerges with a cellphone and white earplugs, the blue-and-white bandana now re-arranged around his head. He steps onto the pathway cutting across the park. The crowd moves to a patch of grass.

Aakash plugs in the earphones, and presses Play. To give the audience a cue, he starts singing. “Aai pyar ki rut badi suhani, tu darna na o’ meri rani…” from Kaho Na Pyar Hai, Hrithik Roshan’s debut film in 2000.

Now the others have taken the cue, and he stops singing, and enters his dance trance, copying the moves of the star, even the expressions. There’s competition. In the twilight hours, the park near the Bangla Sahib Gurdwara in New Delhi becomes a stage where street children, who live in the shelter homes run by some NGOs here, pay homage to Bollywood.

Praveen is next. “Body ke andar automatic jhatka,” he says. “Bollywood jhatka.”

Now others join in. Ten-year-old Vishal is wearing patent leather shoes, several sizes bigger than his feet, and breaks into a tap dance routine. Done proving his dance smarts, he breaks into a Bhojpuri song— “Jab lagawelu tu lipistick, hile la Ara district, jila top lage lu, lollypop lage lu.”

All of them live together in the park, in three tin shed shelter homes set up by different NGOs. In one of them, live homeless women. They too are watching the boys perform, crouched under a tree. The evenings would be dreary if not for such things. Pooja, a little girl, has been watching from a distance. She walks over, smiles through her crooked teeth, and starts dancing.

Shekhar just stands by. Later, he tells Dedh Footiya’s story. His mother passed away at an early age and his father was an alcoholic. He dropped out of school, and ended up in this park.

“I want to be someone. Zindagi toh ek aag ka dariya hai, aur ise paar karna hai. Everyone wants to be a hero. But those are dreams. You need talent,” says Dedh Footiya. He is 18, and likes Hrithik Roshan, whose dance moves he has mastered by watching his films many times over. His mobile phone has no connection; he uses it to store songs. He is a serious man, and not used to talking much.

Praveen can talk. He ran away from home, was taken to a juvenile home in Haryana at age eight, then to another in Delhi, from where he escaped in 2005. “I wanted to be an actor but didn’t know how. He started doing drugs. Ab daba ke nasha karta hoon, aur dance karta hoon,” he says.

There are others. Like a shy young boy, who has no hands, and kind eyes. “Mera na ghar hai, na baar,” he says. Or a man who walks on crutches and calls himself Brigadier Suraj Pratap Singh. At 29, he looks older than his age. Street life can do this to you, he says.

“I have a dream. I want to make a film like Dosti on disabled people,” says the Brigadier. The 1964 Rajshri Productions movie told the story of a blind boy and his crippled friend. Singh, who is originally from Patna, wants to do a remake in colour. Maybe act in it too. “In this world, we are the rejects,” he says. “But in the world of films, there’s space for everyone. We can all be heroes.”

“Dilli dilwalon ki,” a man shouts. “Yahan style ke liye aate hai. Then we turn to Bombay, that brutal city where we walk on fire. We will all be tested.”

“You know, I have a plan,” says Anurag. “Let me tell you about it.” He is a first-rate pickpocket, who has spent time in Tihar jail and other prisons. He wants to be a Bollywood star. “I will go to Dadar railway station, then take a taxi from there. It will cost me Rs 25 to Mumbadevi, and after I have paid homage, I will return to the station. I will either become a hero or a pickpocket,” he says. “Those are the only two things I know.”

Cut to platform No. 7, New Delhi railway station.

Shakeel, Salman, Krishna, Vijay, Arjun, Aakash. Runaway street children. Ragpickers, gang members, Bollywood aficionados.

They crawl down the iron columns like monkeys. A few station themselves up on the beams, smiling and waving. “Duniya mein aaye ho toh, doston, mauj karo,” Salman says, as he walks towards the coach of an empty train with a bunch of them inside. They are taking a break. When the next train pulls in, they will resume combing its coaches for plastic bottles, aluminium foil, anything to sell. Salman, they say, never wears a shirt. Not after he saw Salman Khan showing off his toned body in the movies he watched at Imperial cinema. He took on the name, and walks around with a shirt in his hand. When Tere Naam released in the theatres, many of them got their hair styled like Salman Khan. Long, with a middle parting.

Beyond the smiles, there are stories of abuse and deprivation. There is also the spirit of the child to break free. Many ran away from home to be Bollywood stars. They believed the roles Amitabh Bachchan essayed—the saturnine avenger, the quintessential man of the street who is chasing freedom and success.

When he was young, Shekhar’s uncle would take him to the neighbour’s house to watch the serial Mahabharat. He’d stick around for the evening feature film, and then when the village slept, he’d sneak into the neighbour’s house, and watch the 9 pm film. When he was 11 years old, he’d hop on the train and go to Sultanganj to watch matinee shows with other boys. By then, Shekhar had strayed. He bunked school, gambled and smoked beedis. A pious, doting mother, a hardworking father and a comfortable childhood were not enough to hold him back. He ran away and for six months lived it rough on New Delhi railway station before being rescued by Salaam Baalak Trust, an NGO that works with street children.

“I said no to an internship because I wanted to be an actor and spent all my time doing plays. Of course, I didn’t have the looks. I wasn’t fair or tall. But I knew I could make people cry. Now, I think I can make them laugh.”

His friend Javed remembers Shekhar seeing a movie every Friday. “He would work hard for the money to buy the tickets. But his dreams shattered and he got addicted to drugs. Salaam Baalak gave him many opportunities but he was a lost case. He would wear a red bandana like Shah Rukh in Ram Jaane. Because he wanted to be an actor so bad, it ruined him. He said ‘no’ to everything that came his way. He just wanted to act.”

Shekhar has written a script. The story of a street kid, the life he knows best. It’s the story of a girl who ran away and came to Delhi, the story of her journey. “I am wondering if I should play the character of a pimp or the brothel owner,” he says.

“Have you been to Khalsa restaurant?” Anurag asks.

“Where is it?”

The langar at the Bangla Sahib Gurdwara, he says. That’s where they go to eat, and then return to the park. They work odd jobs and live on the streets. Salaam Balak Trust was set up from the proceeds of the highly-acclaimed 1988 Mira Nair film, Salaam Bombay, which chronicles the lives of street children. The NGO named after the film rescues and rehabilitates street children. Now there are other NGOs too that provide shelter homes, training and education. The children live in these cramped shelters, watch television, and learn the alphabet from volunteers of the Trust, often people who come visiting from other countries. The Salaam Balak Trust gets a steady stream of these overseas volunteers. Once they turn 18, they have to leave or join other shelters like the ones run by Prayas in this central Delhi park. Anurag calls it ‘half-way rehabilitation’ because when they leave they are still not ready to make it on their own. Sometimes, they join the staff of the Salaam Balak Trust itself, but those options are limited.

Not all stay or even join the shelter homes. Aakash and Salman, for example, wouldn’t trade their lifestyle for the promise of education. They say only the privileged can find success, the rest just get by. And if you have to get by, they’d rather do it on their terms. A young filmmaker, Aatish Dabral, who spent months with Shekhar and two others, made a film called Badal Gaye Hum as part of his college project. The film is about street children and their lives. Dabral describes them in these words: “Each of them is the hero in his own story.”

“I got to see their involvement with films,” he says. “In one of the scenes, a voiceover goes: ‘Hamari zindagi mein problems toh bahut hain, par in teen ghanto mein, jab film chalti hai, hum kho jate hain.” When he screened the movie for them, they clapped. Shekhar danced. It is one thing to imagine themselves as heroes, another to see it on screen.

Rafiq Sheikh worked out at a second grade gym to get his body in shape. He tried learning English and learnt horse-riding at Bombay’s Chowpaty beach. He figured these were essential actor skills. At the auditions, and he went to many, he got rejected. He’d curse his stars, and everything else. But he kept at it. At more than 6 feet, he says he can beat Salman Khan in screen presence.

“Give me a chance and I will prove it,” he says.

He came to Bombay Central station years ago. His father married a Bangladeshi migrant, Zarina, after his mother passed away. When he died of alcohol, she kicked them out. At the time, they lived in Rajgadh, Maharashtra. Like Amitabh in Khuddar, Rafiq brought his two siblings to Bombay Central and started working as a coolie and sleeping in the yards. The spot where Salman Khan waits for Kareena Kapoor in Bodyguard used to be his spot.

Rafiq is 31 and now married. He is not ready to give up what he has chased for years. He still goes for auditions, still in pursuit of that elusive “one chance”.

“My father was also a big Bollywood fan. He used to tell me, after watching Khuddar, that he would make one son a police inspector and the other a thief. I was the one he had planned on making a cop.”

At the Bombay Central coffee house, he introduces his friend, Ram Naresh. Ram is a bit older than Rafiq. His father was a drug addict and he was forced to work at the station to provide for his mother. “We are like Dharmendra and Amitabh in Ram Balram,” he says.

The two met years ago as children, trying to survive on the streets of Bombay. They remember their first film together at Metro cinema. They were dirty and wearing shorts. Of the ten rupees they earned picking bottles at the station, they spent eight on tickets. From then on, they’d watch at least two films a day in the Pila Haus area. Most of the money they made went on tickets. “Some- times, we went to Film City (the studio in Goregaon), a regular hangout for street kids. In those days, they’d let us on the sets and we’d jostle to get near the camera. Whatever we have learnt, we have learnt from the movies,” says Ram.

He wanted to be a cameraman, and always stood behind technicians who manned the camera. He claims that by looking at a shot, he can tell where the camera was placed. Rafiq wanted to be on the other side of the camera.

“They used to say I look like Akshay Kumar,” he says. “I hunted for those pointed shoes, and used to wear them on our trips to Film City.”

When they were rescued by an NGO, Childline India Foundation, they got invited to the Oberoi Hotel rooftop for an event. “We wore chappals,” he says. “The invite said ‘formal dress’ but we were confident. We had learned to talk like big people from the movies. We were actors, we could imitate anything. So, a lot of people were surprised to find that we were street children.”

Rafiq once went to audition with filmmaker Karan Johar. “He said I wasn’t fit for the role,” Rafiq says. “It was a small role, but I was so angry. I said: ‘You give ten takes to Salman Khan, but for us, you wouldn’t give a second or a third chance.’”

The two are now small-time contractors for freight trains, and spend most days at Bombay Central station. On weekends, they go home to their wives in Virar. Street life is addictive, they say.

“One day we will make our own film. Ram will man the camera, I will act,” says Rafiq. “Slumdog Millionaire is our story. Only that they got there first. We were still figuring out our lives.”

“What’s to learn? Thoda masala, thoda dance, thoda pyar,” Ram says. “Apne ko pata hai, picture mein kya dalta hai.”

Rafiq’s ears are pierced and he wears studs.

“In Dharamveer, Dharmendra wears studs, so I thought I should also do it,” he says.

When Karishma Kapoor and Rahul Roy’s 1992 movie Sapne Saajan Ke was being shot at Film City, both of them were there, waiting for the camera to pan to them. “I tried to run ahead to get into the frame, but I wasn’t there when I went to see the film,” Rafiq says.

On the sets of Andaz Apna Apna, Rafiq and Ram decided they would not run anymore. They would instead try to work their way up. That dream is still far away, but their life still has meaning. Ram and Rafiq volunteer at the Childline NGO and help other runaway children find a footing in life. They didn’t get lost, and they want to see to it that others don’t.

Ram once fell in love with a bar dancer. She’d come to Bombay Central with food for him. She used to wait for him to enter the bar before she danced. They would go for long taxi rides, stay in hotels, smoke and drink. She loved him and he would go shower money where she danced. It didn’t work out eventually. “Such love is doomed. But no complaints. If there was a heartache, I’d listen to sad songs. If there was a happy moment, love songs. Bollywood for every occasion,” he says.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

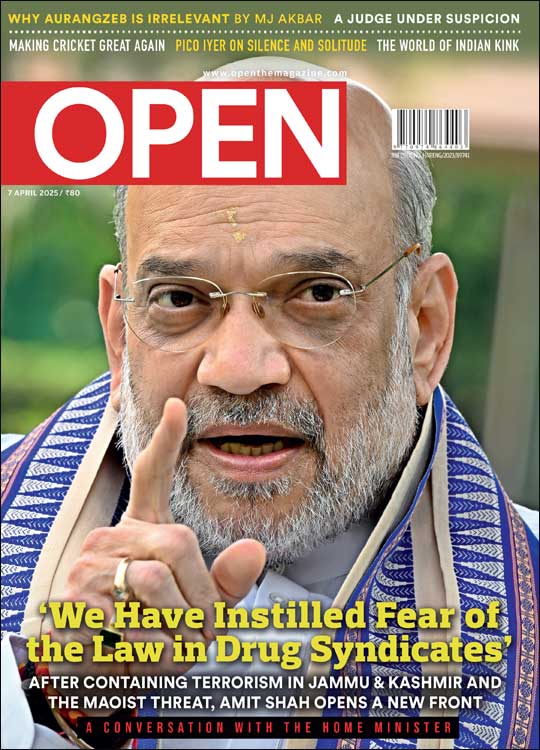

‘We Have Instilled Fear of the Law in Drug Syndicates,’ says Amit Shah

MOst Popular

4

/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Cover_Amit-Shah.jpg)

More Columns

BJP allies redefine “secular” politics with Waqf vote Rajeev Deshpande

Elon Musk attracts sharp attack over ‘swastika’ from Indians on social media Ullekh NP

Yunus and the case of a "land locked" imagination Siddharth Singh