When a City Sinks

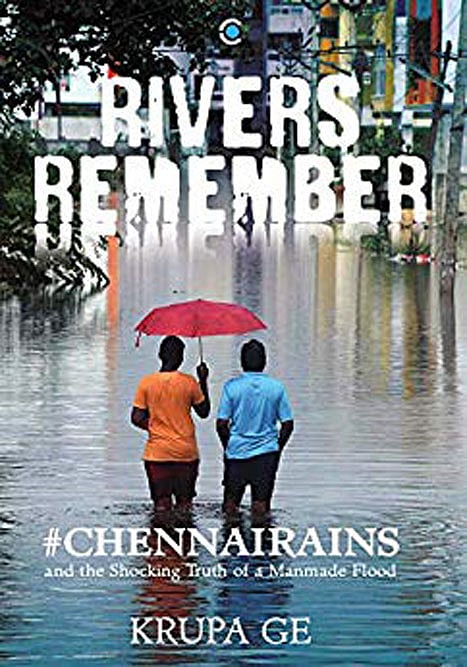

Imagine water rising stealthily in your house as you sleep, your furniture becoming steadily submerged in water. Imagine escaping with your lives and a precious few belongings, returning a few days later once the water has receded to find every inch of your material life covered in fetid sewage. In December 2015, this was the fate that met thousands of households in the city of Chennai. Among those devastated by the floods, described by government officials as a once-in-a-hundred-years’ event, were the parents of journalist Krupa Ge. The contents of their ground-floor home were destroyed as they took shelter in a neighbour’s home on the third floor. Ge was left with a seemingly unanswerable question, ‘How on earth did this happen to us?’

Over the next three years, Ge investigated if the flood was indeed a freak natural occurrence that could not have been prevented as the government claimed or if there were human-controlled factors that made the flood both more likely and more devastating.

There is no hyperbole as Ge delves deeper into the stories of those who survived a time of bewilderment and terror as they tried to return home, look for loved ones or do their jobs in extremely trying circumstances. Ge traces the source of Chennai’s water along with the recent history of mankind’s involvement with these water bodies. One of the stories Ge unearths is that of a gynecologist in a peripheral part of Chennai who had to ensure the safety of heavily pregnant patients even as her clinic was cut off by the floods. She receives no assistance from the authorities in evacuating her patients and must count on a nearby hospital for help. But the government’s role in the stranding of the clinic does not end or begin there. In a moment that will stay with me a long time, the doctor notices lotuses blooming on her property sometime after beginning construction for the clinic and realises to her dismay that she has unknowingly been sold land where a lake had once been.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Ge shows how Chennai had been left vulnerable to severe damage through the government’s decision to sell land and approve construction on flood plains and sites once occupied by natural water bodies.

Ge doesn’t suggest that there is a single, sweeping factor to blame for the catastrophe. She finds through RTIs, interviews, and research that manifold failures precipitated extensive damage to the city. Multiple bureaucratic and political failures—undue delays in approving timely release of water from dams in the light of heavy rainfall, myopically approving wide-scale construction on flood-prone land, archaic disaster management plans—contributed to the state’s incompetence in preventing, mitigating, and responding to the floods.

Ge’s work is that rare slow reportage that could be instructive to multiple stakeholders in present-day India if they allowed it to be. It’s one of the strongest works of narrative non-fiction to come out of India recently—elevating reportage with nuanced, even-keeled writing that tells the story of a place as much as of an event. It makes one wish for similar scrutiny of the relationship of other urban centres to development, sustainability, and disaster preparedness and management.