Schmoozer’s List

The directory of India's most wanted phone numbers

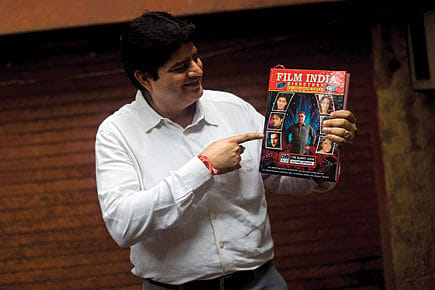

Deepak Malhotra, associate editor of Film India, knows that to produce his kind of film publication takes a kind of madness. "Others started film directories too, but they gave up. It takes a lot of persistence."

That is an understatement. Film India, published in alternating sizes every six months, is as much a phone directory as a study in the migratory patterns of Bollywood. Every six months, Malhotra reckons, "about 40-50 per cent" of India's film folk change their numbers. So, every six months, a small team from Malhotra's office calls every number in the phone directory. A changed number means "calling, calling, calling, asking people they have worked with recently" until a person's number is finally found. Addresses are physically verified. There are "over 20,000 contacts" in Film India. Sometimes, numbers change right before the 25,000 copies are printed each November and April. Sometimes, people die: Nirmal Pandey's phone number lives on in the April 2010 edition, two months after he died of a heart attack (amended). Malhotra smiles when asked about the scale of the work, but then softens the effect, saying that sometimes people call by themselves to inform them of a change in contact details.

Malhotra's office is in Bandra, a fair way from Hindi Cinema's headquarters: Lokhandwala. When I ask him about it, he reminds me that the film industry once spanned a swathe of Bombay from Bandra to Juhu, and moved northwards with the inflow of new talent seeking cheaper suburban housing. He and his office are well-hidden in other ways. Where he works is in plain sight, on the ground floor of a building in a busy Bandra bylane, obscured only by a tree. His desk inside this office—with just enough space for, say, four or five parked cars—is swamped under a deluge of pens, papers and phones. On one desk, he has four cord phones. His wife, who works with him, frequently sits on one of the office's 15 overused chairs, occasionally losing her balance because of a missing wheel. Computers line the walls, and documents, fliers and directories occupy significant real estate. Above Malhotra—not a small man—whirs an impossibly tiny fan. Here, in this unlikely setting, is where the work gets done.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

A hierarchy is evident in the pages of this phone directory: there are those who want to be accessible, and others who don't need the attention. Salman Khan's residence number is listed here, but there's no personal contact. Naseeruddin Shah remains out of reach as well. But Jackie Shroff has five numbers listed here, including a personal cell number. So does Johnny Lever. Although Malhotra says his publication is meant for the people it features on its pages, it's safe to say that this tome is of greater use to people who hope to get somewhere. This is only a theory, but a glance through the full-page ads at the start back up theories of this kind. These pages advertise locations for hire, studios, equipment rentals, a cosmetic surgeon, playback singers, aspiring actors, astrologers, and a director from 'Hollywood to Bollywood… with Best Wishes & Compliments to Subhash Ghai, Bonny Kapoor, Mahesh Bhatt, Amitabh Bachchan, Anil Kapoor, Govinda, Salman Khan, Shahrukh Khan, and all Bollywood Friends'.

Still, Malhotra knows that Bollywood numbers can be a menace in the wrong hands. He keeps two phone directories, one that is published, and the other for himself. "I have every number. I can get any number. But people know by now that what we do is for purely professional reasons." He adds that he keeps his interactions with contacts short, telling them that he'd like to list their number, or if they aren't keen, then a manager's number, and that he might call back once or twice a year to update the directory. "They don't mind that. If I put in their real numbers, they'd get hundreds of calls a day," he says. The fear of misuse also means that the directory isn't disseminated in the usual places. Copies are rarely found at bookstores, for example. To make up for this, Malhotra has the directory delivered to people's homes.

The economics of producing a niche directory whose characters steadily increase and whose contact details never stop changing might sound iffy at first, but Malhotra says that the business is a viable one. The hardest part, he insists, was getting the venture going. Malhotra's father, Ramesh, began the directory in 1984 as a side business; his real focus was on the family's printing press. He reckoned a film directory was a good idea. The first issue was laid out by hand, like most publications at the time, and was 60 pages thick. Malhotra, 14 years old back then, says he would carry the directory door to door, and would repeat the exercise for new numbers. The first two years didn't pay much, but by the third, Malhotra noticed that people could see value in keeping the directory afloat. Some even paid for the previous two years.

As it stands now, the directory is 500 pages thick. It contains numbers, but also standard contracts, a list of star birthdays, and a brief history of Mumbai. It even lists numbers from the Bhojpuri, Marathi, Telugu and Tamil film industries. Each of its pages has an advertisement of some kind. A typical banner ad sells for Rs 500, and full-page ad inserts are sold for over Rs 10,000.

When I ask Malhotra what his production costs are, he says (nicely) that he doesn't want to talk about it. But he has plans to branch out. In addition to the film directory, he publishes Music India, a slimmer directory, and he has made moves to bring out Television India as well.

But the business of numbers remains as tricky as ever. The industry's various associations provide Film India new and updated numbers, but there are several that slip through the gaps. I ask him to give me an example of how he would approach the task of acquiring the number of an elusive subject, such as Anurag Kashyap (who changes numbers frequently). At the mention of Kashyap's name, Malhotra's calm exterior cracks— if only for a moment. He allows himself a huge smile, and laughs. "Anurag? He was very, very hard to reach."