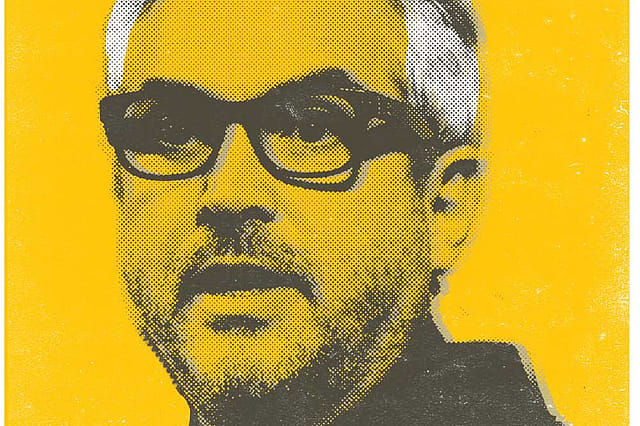

Alfonso Cuarón: The Romantic

ONE OF THE earliest teasers of Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma came out sometime last year. One sequence had a camera pan a wide sweep from left to right, from a shop on perhaps the first floor of a building to a glass window through which you could see the pandemonium of a swelling crowd below, transporting you instantly to that shop, at a slightly lower height than the adults, as though you were a child gazing through the window at the city and the trouble brewing in it.

All that was known then was this was going to be Cuarón’s return (after his big Hollywood productions) to Spanish language cinema. That it would be set during the student demonstrations of Mexico City in the early 1970s and based on Cuarón’s childhood in the country’s capital. One may be forgiven for having thought that the film would revolve around those protests (I certainly expected as much). That it would be this large political event that would propel the quiet story of a family.

As it turns out, it wasn’t going to be that. Like its colours, the world outside the family would be muted. The movie would be an intimate memory of Cuarón’s childhood; a series of vignettes and images of an upper-class family and a housekeeper of Mixteco heritage—warm, funny and sad—as though glimpsed in a private family album.

The film is spectacular. It is arguably 2018’s most striking work. It feels singular and significant in a way that no other film from last year seems. It has picked up a bunch of awards already, winning two Golden Globes recently, for the best director and best foreign language film. It didn’t get nominated for best drama because the Globes’ rules only allow English-language films to be considered in this category. But the Academy Awards has no such categorisation. And come January 22nd, when the Oscar nominations are announced, it is likely to become the first Spanish-language production to land an Oscar nomination for Best Picture. It might even go on, given the buzz and the exceptional acclaim, to win it.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

That would be a significant moment. Only 10 foreign-language films have ever been nominated for Best Picture (none has won). And more interestingly, such a win would finally bring Netflix to the high table of cinematic prestige. Roma is the streaming giant’s biggest bet yet for recognition. It didn’t just bankroll this film, which despite the high status of its director and crew, was a risky project on paper. It even broke away from its own strategy and released the film in theatres first-—albeit limitedly—before its platform so it could be considered for awards.

An interesting debate has arisen out of this. The film cries out to be seen on a large screen. And since this is Netflix, it is intended to be consumed mostly at home. Many unsurprisingly have criticised the platform for suppressing the big-screen identity of its own product. Cuarón himself has mentioned in several interviews that he would like his film to get a larger theatrical release. During the press interaction after his Globes’ wins, Cuarón was asked whether the success of the film would mark the end of independent theatrical experiences. “How many theatres did you think that a Mexican film in black-and-white, in Spanish and Mixteco, that is a drama without stars—how big did you think it would be as a conventional theatrical release?” Cuarón asked in return and added, “...Something we must be very conscious of is that the theatrical experience has become very gentrified to one specific kind of product.” These are valid points. Cuarón hasn’t made the debate easy. He has made a film that would probably never have taken off had it been intended only for halls; yet he has also made it so beautiful that anything but a large screen would appear a waste.