This Is Us

When Reema Kagti made her first film in 2007, she daringly made one of her characters, a non-resident Indian named Bunty played by Vikram Chatwal, a closet homosexual. But as she recalls now, she couldn't get into it in detail, certainly not in the way she could with the mini-series she co-directed and co-wrote this year for Amazon Prime Video with Zoya Akhtar, Made in Heaven, which had a gay lead. Ditto with Sudhir Mishra. He's been trying to make The Nawab, the Nautch Girl and The John Company, set in 19th century India, as a movie for the past decade. It will finally see the light of day as a TV series soon. For Kubbra Sait, actor and anchor before she became the stunning Kuckoo in Netflix's Sacred Games, the career has jumped trajectories and opened more doors to conversations. "I'm loving riding the new wave," she adds.

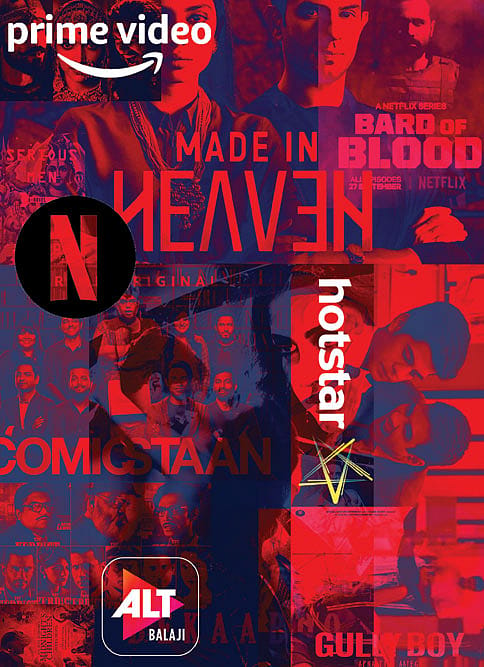

Streaming services have liberated the Indian filmmaker and actor as never before, allowing them to break through self-imposed censorship and socially assumed norms of acceptable family-viewing. Reed Hastings' story of how Netflix, the first streaming service in the world, may have changed several times but the Los Gatos, California-based giant which started as a company selling DVDs online in 1997 began streaming entertainment in 2007. By the time it came to India in 2016, viewers, having been fed on a steady diet of Sex and the City and Breaking Bad on TV, were ready to be entertained, but with their own stories.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

As the EY report on the media and entertainment sector for 2019 A Billion Screens of Opportunity puts it, driven by global streaming platforms' localisation strategy and domestic streaming services' drive to grow their audiences, as well as the increasing number of regional TV channels, the demand for original digital content increased by around 1,200 hours in 2018.

It was also because the number of streaming platforms rose. Beginning with Amazon Prime Video and Netflix in 2016, India now has 30 streaming platforms. According to the US entertainment magazine Variety, 21st Century Fox's Hotstar has 150 million monthly active Indian users, Zee 5 (the streaming division of Zee Entertainment), 56.3 million, Times Media's MX Player, 75 million daily, and Viacom 18's Voot and Sony's Liv, 35 million each; AltBalaji has 13 million subscribers, and Eros Now, 16 million.

Indian viewers have hit the jackpot. Good, bad, ugly—they are watching movies and television from across the world and cinematically produced original shows from their own country. Where once there was just Amazon's Inside Edgeand then Netflix's Sacred Games, now there is a deluge. And surprisingly, they are willing to pay for it. According to the EY report, the number of Indians who paid for content increased from 7.5 million in 2017 to 12- 15 million in 2018. As media analyst Amit Khanna says, "Content has changed because more people are exposed to global shows and so storytelling and production design have improved. In major metros, a younger demographic, more familiar with all kinds of content online on smartphones, is patronising more rooted cinema."

The big daddies of streaming services know this, and they know the number of smartphone users in India is over 340 million, more than the population of the US. They also know—according to a study by the Omidyar Network—that Indians spend 30 per cent of their time on mobile phones on entertainment, second only to social media. In terms of data, they use upwards of 70 per cent on entertainment.

"Digital platforms provide an audience for niche projects. They encourage stories of women, diversity and inclusiveness, which a conventional theatrical release doesn't. Also, the lack of censorship results in creators not censoring themselves," says Reema Kagti, producer

As Vijay Subramaniam, director and head (content) of Amazon Prime Video India, puts it: "The presence of a strong regional mix of content helps get viewership from across the length and breadth of the country. So we remain invested in bringing the latest theatrical releases across different languages on Prime Video. Right now we have content in nine Indian languages. We've just recently greenlit the first Tamil Amazon Original: Comicstaan Tamil." Everyone's tastebuds are picking up on different flavours. Amazon Prime Video customers from Tier II/III cities are watching blockbuster international movies as much as they love watching mainstream Hindi films.

Even the way people are watching is being transformed. Most Netflix subscribers in India, for instance, kick off their binge while on the road. Indians are 82 per cent more likely to stream at 9 am, a behaviour that continues on the ride home too: peak streaming in India is at 5 pm. Indians, adds a Netflix spokesperson, are among the top mobile downloaders in the world for their content. This is the market Reliance Jio wants to retain by inking partnerships with as many content providers as possible. Along with an existing partnership with Eros Now, it has also set up Reliance Studios to produce content for Jio's 306 million subscribers, as it intensifies competition with competitor Airtel, which has 325 million users and has signed a content deal with Amazon Prime.

With connected devices, living-room viewing is also on the rise, says Amazon Prime Video's Subramaniam, especially in the metros.

For filmmakers, it is time to tell the stories they've long wanted to. And they are making the most of the rising demand and rates. Rohan Sippy, who co- directed the official version of The Office for Applause Entertainment, which is streaming it on Hotstar, says this competition has reduced or removed barriers to producing and even distributing on platforms such as YouTube which gives creators a chance to produce work like no previous generation has ever had. Like AltBalaji and Ekta Kapoor. Bolstered by the sale of a 24.9 per cent stake in Balaji Telefilms, AltBalaji's parent company, for Rs 413 crore, Kapoor has been able to make entertainment with an eye on three different segments: mainstream TV, independent movies and digital shows. And that's because she is constantly hearing people. As she told Film Companion, "I have about 20 curators with me and they are constantly finding new people. We never say no to anyone. We hear everybody's story. I keep saying I don't care about biodatas—keep them aside. Between rural and urban is a huge audience called the urban mass which is what I'm actually catering to. Urban mass is the world between Netflix and Naagin, which is a lot of people. This means I'm not the Naagin audience but I can't watch Narcos either because I've not learnt English in the best school."

As she notes, even the rural audience has three viewing patterns. One is communal, which is going to films with family and friends. Two, family viewing, which is content that the elders in the family allow you to watch or what is acceptable for you in front of them. Third, the time you spend with yourself—your individual viewing pattern. So even on AltBalaji, she is able to make the schlocky, sleazy Bekaaboo as much as the more serious The Verdict, a forthcoming mini- series based on the Commander Nanavati case.

"I have about 20 curators with me and they are constantly finding new people. We never say no to anyone. We hear everybody's story. I keep saying I don't care about biodatas—keep them aside. Between rural and urban is a huge audience called the urban mass which is what I'm actually catering to. Urban mass is the world between Netflix and Naagin, which is a lot of people," says Ekta Kapoor, producer

Walking new ground can be punishing, and Rangita Pritish Nandy says as much when talking about producing Four More Shots Please!for Amazon, which deals with everything from messy divorce to lesbian love. "Filming the season was not easy—we were walking new territory for India—but all of us came in to tell an honest story and eventually that's what reflected on camera," she says.

Filmmakers are either partnering streaming platforms, exclusively, or are happy selling their work to the highest bidder. Excel Entertainment works closely with Amazon, having made Inside Edge, Mirzapur and Made in Heaven for them. Shah Rukh Khan and Netflix have a great relationship, with the superstar's first home production, Bard of Blood, based on Bilal Siddiqi's book and starring Emraan Hashmi hitting screens in September. Then there are filmmakers such as Kabir Khan, who is creating The Forgotten Armyfor Amazon while also signing up for work with Hotstar.

WORDS ARE FINALLY getting their due. Books are being adapted for movies and mini-series. Booker Prize winner Aravind Adiga's Selection Day and Prayaag Akbar's Leila recently made it to Netflix as a mini-series with Deepa Mehta as creative producer, while Sudhir Mishra is adapting Manu Joseph's A Serious Man with Nawazuddin Siddiqui in the lead and Vishal Bhardwaj is tackling the mammoth task of Salman Rushdie's 1981 novel Midnight's Children.

Adapting well-known novels helps in reaching a global audience. In the case of Sacred Games, adapted from Vikram Chandra's page-turner, two of every three viewers were outside India. Viewers are more accepting of other cultures now, whether it is Indians watching the Israeli show Fauda or Americans becoming addicted to Amazon's Breathe—as thriller writer AJ Finn (aka Dan Mallory) told me he was.

But it is also about who owns the biggest library in this brave new digital world as the time between theatrical window and movie production available for video-on-demand shrinks. As Amit Khanna says, the entire planning, distribution and exhibition of films are now digital. Film music is released only digitally and now digital companies are also becoming large investors in film production. "Home video has been replaced by online and on-demand video," he adds. Big-banner movies are entering pre-release digital deals. According to the EY report, of the top 25 box-office grossers in India released between June 2017 and June 2018, Amazon Prime bought 13 digital rights. Netflix bought four of the five top box-office Hindi films ever and Zee 5 bought digital rights of six films. Those who have a back catalogue, like Eros Now, which has a library of 12,000 films, have an advantage.

No one knows where the money will eventually come from. Will advertising be the primary revenue source or will subscriptions take off? For now, a hundred stories are blossoming. "Anyone, anywhere is now connected to the world," says Sudhir Mishra. "Filmmaking will become decentralised soon and Mumbai, Chennai and Hyderabad will lose their monopoly on storytelling. A young person from Jamshedpur or Jabalpur who has never even been to Mumbai may well go straight to Cannes."

It's an exciting idea. Gay heroes, lesbian love affairs, transgender cabaret dancers, transgressive fathers-in-law, dystopian futures and Radhika Apte. As Reema Kagti says: "Digital platforms provide an audience for niche projects. They encourage stories of women, diversity and inclusiveness, which a conventional theatrical release doesn't. Also, the lack of censorship results in creators not censoring themselves."

Expect much more truth-telling and plain-speaking in the next few years.