The October Test

BY THE TIME Juan Ramón Jiménez won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1956, the Nobel laureate he had translated, along with his wife Zenobia, and popularised in the Spanish-speaking world had been dead for 15 years. Rabindranath Tagore remains the only Indian to have won the literature Nobel, something that couldn't have been foreseen 106 years ago, nor perhaps bothered about. The literature Nobel in 1913 didn't yet have the prestige it would come to acquire nor caused most of the serial controversies that would call its motives and relevance into question. Tagore wouldn't have won the Nobel without WB Yeats' intervention in the translation. Tagore's insistence on translating himself was a literary suicide that saw him soon forgotten in Europe. Yet he continued to be read in the Spanish-speaking lands because of Jiménez, who is hardly remembered today as Tagore's greatest translator.

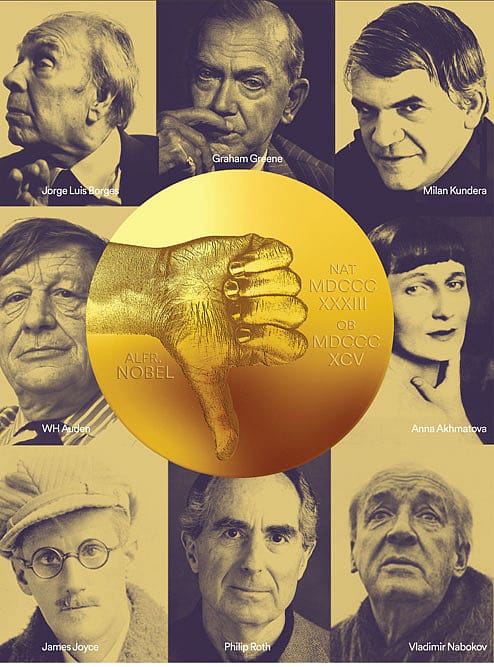

A few years after Jiménez, another poet, and a great one, was denied the prize, allegedly, for erroneously translating a Swede. It's difficult to tell whether WH Auden sinned more in mistranslating—some say deliberately—Dag Hammarskjöld or in proclaiming, in Scandinavia, his belief that the UN's second Secretary General and Nobel Peace laureate was homosexual, like himself. Those inclined to view Tagore's Nobel as an early acknowledgment of 'world literature' by the prize are reminded that Tagore was not honoured as a poet writing in Bengali, even if his Nobel counts for the language. And l'affaire Auden still serves as an extraordinary example of everyday pettiness.

2025 In Review

12 Dec 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 51

Words and scenes in retrospect

The literature Nobel always was, and continues to be, a Eurocentric prize and that isn't necessarily a bad thing. The Academy is Swedish and its capacity for adequately evaluating works of literature from around the globe—with the availability and quality of translations not an insignificant determinant—has naturally been suspect. That is a fact. And almost 120 years after the first laureate, we would rather the Academy stuck to the world as it looks like from northern Europe. Not without irony, it's the very stature of the prize and the occasional sightings of distant horizons from Stockholm that have turned out to be the Academy's nemesis.

Olga Tokarczuk is the first eastern European writer to get the literature Nobel in a decade since Herta Müller (2009), who, language and nationality notwithstanding, wrote behind the Iron Curtain. Between Müller and Czesaw Miosz (1980), there were three laureates from eastern Europe: Hungarian Imre Kertész (2002), Polish Wisawa Szymborska (1996) and Czech Jaroslav Seifert (1984). Tokarczuk is the sixth Pole to win the literature prize—if we count Isaac Bashevis Singer's 1978 Nobel as also a Polish win (he had emigrated to the US in 1935) and discount the fact that Singer wrote in Yiddish (the only Yiddish Nobel)—but only the 11th (including Romanian-born Müller) from an east European country, excluding Russia, Belarus, Greece and Turkey. Of the eastern European nationalities, the Czechs (and Slovaks), Hungarians and Balkans have a conspicuously thin presence—and that's accounting for the debate whether Milan Kundera is Czech or French. The second and last Greek to win was Odysseas Elytis in 1979. (The greatest Greek poet in many centuries, the Alexandrian Constantine P Cavafy's works were read mostly in pamphlets and private booklets in his lifetime.) On the other hand, Sweden has eight laureates, Scandinavia 14 (Denmark and Norway three each) and the Nordic countries 16 (Finland and Iceland one each). Spain has six but the Spanish language 11, including Latin America and the Caribbean but excluding St Lucian Derek Walcott who wrote in English. José Saramago is the only Portuguese laureate (there's none from Brazil), while the German language has 14, including Germany's eight, Austria's two and the likes of Herman Hesse and Nelly Sachs who ended up outside Germany. French has 14 laureates but France 16, the most for a country, with Ivan Bunin's and Gao Xingjian's Nobels added to its tally.

From any perspective, Eurocentric or otherwise, certain European regions are more 'neglected' than others. Within regions, certain countries (and languages) have won more Nobels than their neighbours. That's true for the Nordic nations too, with homeland Sweden wining most. But if the Academy must be accused of bias, why not Anglophilia of a cross-Atlantic kind since it has awarded a total of 29 to literature in the English language—and more if we count Tagore and the bilinguals Samuel Beckett and Joseph Brodsky?

' "I dreamed about that woman who dreams," he said.

Matilde wanted him to tell her his dream.

"I dreamed she was dreaming about me," he said.

"That's right out of Borges," I said.

He looked at me in disappointment.

"Has he written it already?"

"If he hasn't he'll write it sometime," I said.

"It will be one of his labyrinths." '

After his very brief siesta in the house of the narrator (ostensibly Gabriel García Márquez) in Barcelona on the day he stepped on Spanish soil for the first time since the Civil War, Pablo Neruda emerged to have the above conversation in the story 'I Sell My Dreams' (Strange Pilgrims, 1992, trans Edith Grossman, 1993). The passage may be a curiosity but it serves as literary shorthand for triangulating the three Latin American giants. While there could never be any debate on the Academy's choice of Neruda (1971) and Márquez (1982) within the bounds of literary sanity, the denial of the Nobel to Jorge Luis Borges is perhaps the biggest scandal in the post-war history of the prize.

Borges' sympathy for the right in Argentina (and Chile) was common knowledge but its complexity was seldom analysed. It cost him literature's greatest prize despite multiple nominations, but also allowed critics to ask why defenders of leftist totalitarianisms (Neruda, like Jean-Paul Sartre, was a public defender of Stalinism while Márquez remained a dear friend of Fidel Castro and his regime till his dying day) could be felicitated but the same yardstick wouldn't apply across the political divide. Another Latin American laureate, one of deep associations with India, had caught the post-war wind succinctly: '[José] Ortega y Gasset's name is seldom mentioned these days, whereas Sartre is famous the world over. This may be because Ortega was a conservative, while Sartre is a revolutionary' (Octavio Paz, 'The Two Forms of Reason', republished in Alternating Current, 1967, trans 1983). It was perhaps as simple as that—and the Great Coat the literature Nobel continued to fall out of most years.

Except, it hasn't been as simple as that. Twenty years had to pass after Paz's 1990 Nobel for another Latin American to get there. After the yearly October controversies unleashed by Elfriede Jelinek in 2004, everybody breathed easy when Mario Vargas Llosa won in 2010. The Boom was long dead, but nobody could complain. Yet Llosa's Nobel had briefly fanned the controversy that tended to linger when merit was not in doubt—the question of timing. Llosa, in crossing the political spectrum from left to right, had undertaken the sort of journey a Márquez could—and would—never make since it involved denouncing the Castrist Cuba that the Boom so admired. Llosa lost the presidential election to Alberto Fujimori in 1990 and remains a failed politician but he is the rare Boom genius who successfully transported himself beyond it.

The only question then should have been why Llosa didn't get it at least a decade earlier, after the publication of The Feast of the Goat (2000). But when he did, the Academy—perhaps embarrassed by Harold Pinter's (a worthy laureate but late by three decades) anti-American rant in 2005, Doris Lessing's 'Pinteresque' anti-Americanism (2007), a Herta Müller chosen to arguably commemorate 20 years since the fall of communism in Europe (while Messrs Kundera and Ivan Klíma waited, just as the Norwegian Committee that had given the peace prize to Lech Waesa in 1983 ignored Václav Havel), but above all, by Jelinek—appeared to give its near-nauseating political correctness that alternated with its penchant for unknowns a break by picking a political conservative and a literary heavyweight. And the local context? A year after Pinter, social democratic Sweden had elected one of its rare centre-right governments that would be in office till 2014. Within the Academy itself, Horace Engdahl had been replaced by Peter Englund as permanent secretary in 2009. There were at least two more instances on Engdahl's watch when the Academy's timing came to be questioned: VS Naipaul (2001), right after 9/11; and Orhan Pamuk (2006), hounded then by nationalists in Turkey.

THE LITERATURE NOBEL was in trouble from its inception with Sully Prudhomme. In its early years, it chose to overlook Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov, Émile Zola and Henrik Ibsen among Europeans—and Henry James and Mark Twain among Americans. And when the first American was awarded—as late as 1930—it was Sinclair Lewis. Given the tendency to choose 'locally' every few years—Swedish or Scandinavian writers—August Strindberg never made the cut. James Joyce waited, and eventually died. As did Anna Akhmatova. The Academy is acquitted on Marcel Proust and even Italo Calvino because of their, respectively, early and sudden deaths—just as Cavafy's and Franz Kafka's posthumous fame absolved it of responsibility. But it had a long time for Vladimir Nabokov. Or Graham Greene. And, for Philip Milton Roth.

The case of Philip Roth perhaps came to tell more about the Academy than that of any other candidate in the last two-and-a-half decades, transforming the debate on its criteria, if any, into a cross-Atlantic spat. When Saul Bellow (1976 Nobel) died in 2005, Roth assumed the mantle of the 'greatest living American author'. But the yearly wait had begun with and outlived what Salman Rushdie called his 'late blast': American Pastoral (1997), I Married a Communist (1998), The Human Stain (2000), The Dying Animal (2001) and The Plot Against America (2004). Yet, the first American to receive the literature Nobel after Toni Morrison (1993) would be Bob Dylan (2016). Most of Roth's 'late blast' also coincided with Engdahl's tenure, who found contemporary American literature provincial and parochial. But his departure didn't change the perception that the Academy had become stubborn and wanted to make an example of Roth. Long ago, Harold Bloom had despaired that he had tried but wasn't sure that he would ever convince Stockholm: "[Roth's] not terribly politically correct… And they are." Yet, as we have seen, the Academy could ignore 'political correctness' whenever it wanted too—as it had done with, say, JM Coetzee (2003).

The literature Nobel is best noted for the token it is. Most Octobers, it tells us more about the extra-aesthetic flavours of the literary season in the northern climes. Perhaps the Academy, its reputation hardly salvaged from last year's scandal, needed Roth more than he needed the Nobel. But this time, it was Roth who had cheated them.

Also Read

Editor's Note ~ by S Prasannarajan

The Grand Experimenters ~ by Siddharth Singh and Ullekh NP

Like Father, Like Son ~ by Bibek Debroy