Wisdom of the East

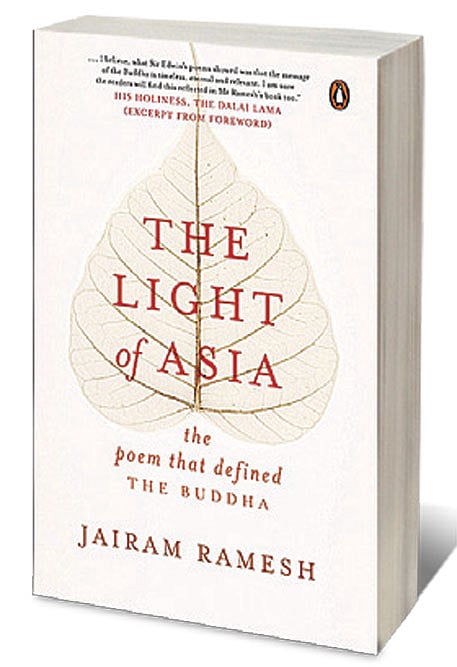

JAIRAM RAMESH’S The Light of Asia: The Poem that Defined the Buddha, declares itself to be ‘the biography of a book’. With its hyperbolic title, it sets out to map the life of a small but influential work, written by Sir Edwin Arnold, that brought the Buddha and his ideas to Western readers and influenced thinkers from the Orient who embraced it with admiration.

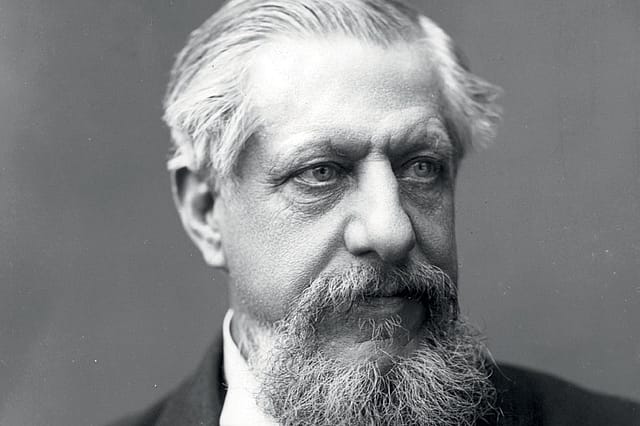

Arnold came to India in 1856 and spent seven years as the Principal of the Deccan College in Poona. Already a poet of some repute (if not undisputed talent), he plunged into the new languages and texts of the subcontinent’s ancient cultures and found much in them to please him. Having lived in India through the horrors of the 1857 ‘Mutiny’ and after, perhaps he sought solace in metaphysical and ethical ideas that were hitherto unfamiliar to him. Arnold was convinced that the books of the East had much to teach the rest of the world and as such, he presented the texts he admired to an English reading public with pride and in the most complimentary contexts. Whatever Arnold might have known of Sanskrit and Pali, it is likely that he worked with scholars and pandits not simply to unravel linguistic knots, but also to better understand the philosophies and world views that their texts contained. Having done so to his own satisfaction, he then reproduced these texts in the manner of his time but with great diligence and dedication.

Despite his respect for Eastern ways of thinking, Arnold was not a critic of the colonial enterprise per se. In his other life, as a journalist and a newspaper editor, he supported the British presence on the African continent. Arnold collected money for the explorer Henry Morton Stanley’s expeditions up the Congo. He also promulgated the idea of the ‘Cairo to Cape’ railway project. Ramesh covers all this in the early chapters and though none of this is new information, the close juxtaposition of this realpolitik with the more exalted emotions that prompted Arnold’s other interests should make us pause and reconsider constructions of both the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ Orientalist. Ramesh, however, does not take his own bait and leaves us to ponder these questions on our own.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

The Light of Asia or The Great Renunciation, was published in the UK in 1879 to critical acclaim and popular appreciation. Ramesh suggests that the book’s instant success could be attributed to the fact that familiar and long-held religious ideas in the West were being challenged—‘mysticism’ ‘spiritualism,’ mediums who could speak with the dead, new notions of the afterlife were moving from radical margins to more conventional conversations about human existence. The charismatic Madame Blavatsky and Henry Olcott had formally established the Theosophical Society in the US in 1875, opening up new worlds to seekers and others curious about metaphysics that were not Christian. Henry Thoreau’s Transcendentalism had already made a deep impact and so Arnold’s paean to the ‘Asiatick’ saviour and his teachings of compassion and nonviolence were eagerly accepted by minds already open to the possibilities of different ways of being and thinking.

Arnold’s version of the life of Gautama is narrated by a young Buddhist monk ‘ . . . because, to appreciate the spirit of Asiatick thoughts, they should be regarded from the Oriental point of view; and neither the miracles which consecrate this record, nor the philosophy which it embodied, could have been otherwise so naturally produced.’ Nevertheless, the opening verses of the poem are resonant with motifs from the birth of the Christ child. The Buddha’s birth as a saviour of the world is long prophesied, his mother dreams of a star ‘whose token is an elephant,’ wise and wealthy men from faraway lands bring gifts in homage to the child of miraculous birth, and so on.

‘The Light of Asia’ is not a translation of any single text. It is likely that Arnold based it on what he knew of the Lalitavistara Sutra as well as on the research and writings of such Buddhist scholars as Spence Hardy and W Rhys Davids. I must say that I am utterly enchanted by the poem and so very disappointed that Ramesh chose not to include it in his ‘biography.’ The few lines from the poem that are scattered through Ramesh’s 450-page tome (heavily researched and filled with quotes from all kinds of other sources) give the general reader no sense at all of how or why ‘The Light of Asia’ could have moved people the way it did. Having access to the poem itself (freely available on the internet) also allows us to think more carefully about what Arnold was doing and the context, both enabling and critical, in which he so lovingly presented his work.

Some years later, Arnold would also create a Bhagavad Gita for English readers. He called it The Song Celestial and it was this book, even more than ‘The Light of Asia’ that persuaded Mahatma Gandhi that the religious and philosophical ideas of his own culture were worthy of attention and serious consideration. Despite the fact that Arnold’s life of the Buddha and his Gita entered a receptive world, for his own sake, it would appear, he was persuaded to write an ‘epic’ poem similar to ‘The Light of Asia’ called ‘The Light of the World’—this poem was about Jesus. It is unlikely that Arnold borrowed tropes from Indian heroic or spiritual narratives to bolster his version of life of Christ. I believe this should be a matter of interest and discussion as we parse the Orientalism that hangs heavy over Arnold’s oeuvre and his moment in time.

Ramesh’s book opens many potentially fascinating doors but enters none of them. As interested readers, we are stuck between incomplete biographies of both a book and its author. Ramesh tells us that Arnold married three times, his last wife being a Japanese woman. But we have no idea what took him from a conventional marriage with an appropriate English woman via marriage to an American woman from a politically significant family to a third marriage, which was surely a most unusual alliance for his time. We glean that Arnold’s interests had proceeded further East to the religions and cultures of Japan, but we haven’t taken that internal journey with him and so we watch, rather than travel with him. Arnold also had much to do with changing the policies that took the administration of Buddhist shrines and monuments away from Hindu mahants and gave it over to Buddhist religious organisations. Ramesh chooses to present the story through the lens of our continuing sleights of hand with the Babri Masjid—such a lens blurs the realities of both the past and the present.

Publicity around The Light of Asia promises that Ramesh’s peregrinations will show us how Edwin Arnold’s heartfelt poem affected Indian thinkers such as Gandhi, Aurobindo, Vivekananda and Tagore. It doesn’t do much of that, hence the biography of the book as well as of its author remain incomplete. But, no matter that our philosophers are largely absent from Ramesh’s enterprise. Ramesh reaches for the complex task of following Arnold and his poem around the world during the last decades of the 19th century, decades that presaged so much change in thought and action, in political systems and society, in the individual’s perception of themself in the world. Unexpectedly, Arnold’s understanding of the Buddha and Buddhism (however idiosyncratic and flawed in terms of contemporary norms and strictures of cultural engagement) speak clearly to the moral and existential questions of our blighted 21st century and for that alone, we must thank Ramesh for bringing ‘The Light of Asia’ back to our attention.