Who Killed My Son?

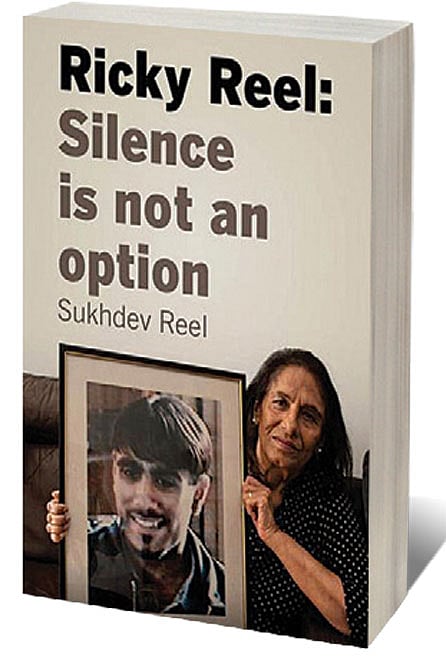

“DO THEY THINK Asian lives don’t matter?” This is a question that Sukhdev Reel has been asking for the past 25 years since her son Ricky went missing in October 1997. Her sentiments resonate with the Asian grievance of being treated as unequal in the UK, a country that takes pride in its multiculturalism. Ricky Reel: Silence is Not an Option (Bookmarks Publications; 250 pages; £10) is a book that she wrote for multiple reasons, one of which, she says, is to expose the racism of the British police that also snooped on her and her grieving family for years, after the death of her 20-year-old son, because her tireless campaign for justice ruffled some feathers in the administration.

The evil of systemic racism has not only refused to die in the last century, but enduring into the 21st century it has also seen a resurgence, especially in the West. Besides other vulnerable groups, Asians, including Indians, are at its receiving end notwithstanding their soft power and influence in Britain’s topmost political echelons. Unsurprisingly, when Tory prime ministerial contender of Indian-origin Rishi Sunak lost to Liz Truss, who is British, in the race to win approval from less than two lakh conservative party voters in the UK, at least one columnist cited race as one of his key disadvantages. Many Indians in the UK also feel that the apathy of the authorities amidst the recent communal tensions in Leicester bring to the fore the Asian pet peeve that they often get a raw deal from the police.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

“I have been meaning to write Ricky’s story for a long time and I know 25 years is a long time. Every time I thought about writing it, something happened, either the police put some obstacles in our way or I became ill—I almost died,” says Sukhdev. She decided to write the book to offer the complete story of Ricky whose case finds mention in numerous legal texts, dissertations and research papers. “But I found them to be incomplete,” says the mother.

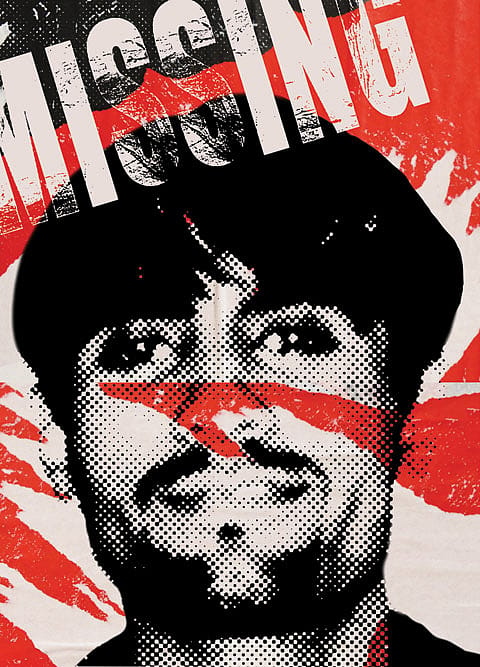

Ricky, a student of computer science, went missing following a racist attack against him and his three friends at the Bentall Shopping Centre in Kingston, South West London. Two white men hollered at them, “Oi Paki” (a racist slur against people of the subcontinent), Sukhdev writes, based on inputs given by her son’s three friends who regrouped after being badly thrashed by the men, forcing them to scatter. The others returned, but not Ricky who was never seen alive after that.

The assault took place on the night of October 14 and Ricky’s body was recovered by investigators a week later, on October 21, from the Thames, not far from where he and his friends were attacked. According to the mother, there were numerous flaws in the investigation, especially as regards tracking the two white men who attacked Ricky and friends. The police, the book says, also did not collect the crucial CCTV data in Kingston—a year earlier, as part of Operation Rainbow, “a counter-terrorist operation in response to the Docklands bombing”, the whole area had a CCTV network in place. Worse, writes the author, who emigrated to England in the 1960s: “Listening to the evidence of Ms Hunt (the alias of the investigating officer) it was astonishing to find that even two years later (in 1999) the police were still desperately trying to dissociate the racist attack and Ricky’s death from one another.”

The distraught mother says she, with the help of well-wishers and strangers, did the actual investigation, not the police. She used to leave home early in the morning for Kingston to speak to everyone from bus drivers to locals with her beloved son’s photo in hand to check for clues. She finds it strange that the investigator at the scene of recovery of her son’s body in Kingston immediately closed the case because he (mentioned in the book as Mr Morgan) saw that Ricky’s zipper was open—and so he concluded that the young man went to the edge of the river to urinate and then fell into the Thames and drowned. The book talks of a BBC journalist who was there at the time and was shocked at such a callous probe. The investigator visited the home of the Reels and repeated his theory and the mother disputed it, saying her son had a fear of open water and would never go anywhere near the river. “It has also been established in previous cases of bodies found in water that the buttons snap due to the pressure of the water,” Sukhdev says.

She complained to the Police Complaints Authority (now called the Independent Office for Police Conduct) because she couldn’t stomach the apathy. The harassment began on day one, insists Sukhdev. When she went to the police station in Kingston after hearing from his friends that Ricky was missing, she was told by the first police officer that she needed to wait for the first 24 hours as per the missing persons’ policy even though he had already told her that Ricky and his friends had been attacked. Another police officer tried to tell her patronisingly that her son may have run away maybe because he was gay. The same police officer winked and added, “Asian people plan arranged marriages for their children, right? You may have been doing that and the result is that he has run away.” That is the attitude of the British Police towards Asian people, Sukhdev notes.

She explains on a Zoom call, with a whiff of bitterness, “Ricky was attacked by racists and let down by the racist police. The police in Britain are institutionally racist.” Sukhdev dismisses claims that her allegations are merely those of a long-grieving mother of a son whose life was cut short. On the other hand, she says, her statements are backed by evidence. About the condescending nature of the police, she recollects from experience, “When my son’s friends went to the police saying they were attacked, the police didn’t take their statement.” As opposed to the normal practice, they were not even shown the photos of known race offenders in the area.

Many years later in 2014, she learnt that her family was snooped upon by police officers. But why? The campaign for justice for Ricky was gaining momentum, and prominent people were getting involved. “We were all raising our voices, and they knew there were many flaws in the inquiry,” she tells Open. Sukhdev, who prefers to keep most details about her husband and other two children private, would only say that they are her pillars of strength. Her children (a boy and a girl) have their careers, but they live with the trauma of the loss of their brother. The trauma was exacerbated because the family liaison officers callously announced that they had found Ricky’s body at the bottom of the river to his siblings, aged 17 and 11, at that time, in the absence of their mother. “My 17-year-old daughter had an asthma attack directly in front of them. She could not talk and was waving her arms in the air for help. Even then none of them paid any attention. My daughter had to crawl up the stairs to get her inhaler. She could have died that day,” the mother says.

The Nairobi-born Sukhdev, however, is glad that her son’s case forced the police to make crucial changes in police law. One of which was the amendment in the missing persons policy—which in the past was that if someone was above the age of 18, the police would not do anything for the first 24 hours. “Thanks to Ricky’s case, they changed the policy: now they will not look at the age, but they will look at the vulnerability,” she points out. “He died because of the colour of his skin,” she says, lamenting that she received no help at all from politicians of Indian-origin in the UK. “The police in England, even at senior levels, are still racist. The change must start from there,” she says. The son’s attackers remain free even as his mother continues what is now a high-profile crusade.