What’s in a Name?

A JOURNALIST AND WANNABE writer named Gregory George Mathews makes a momentous discovery: not only does he share his initials with Gabriel Garcia Márquez, there are many more uncanny resemblances between the two—and so Mathews, convinced he’s an avatar of the great writer, sets out to be another ‘Márquez’. With hilarious results.

‘EMS and the Girl’ has another man donning the name of a well-known figure: in this case, Elamkulam Manakkal Sankaran Namboodiripad, the communist politician from Kerala. A Malayali immigrant in the US, finding an East Asian girl who’s stowed away in his car, decides he can’t risk telling her his real name—so EMS it is.

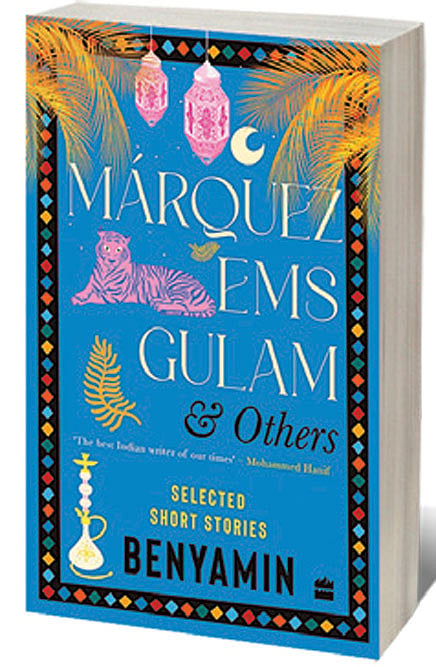

Both ‘Márquez’ and ‘EMS and the Girl’ have people pretending to be someone they’re not. In the first instance, to a ludicrous extent; in the second, superficially. This is a theme that plays out again and again, in subtly varying ways, in several stories of Benyamin’s short story collection Márquez, EMS, Gulam & Others. There are people here—from a mysterious woman whom the narrator stumbles upon in Ireland, to a zealous, overly dedicated postman in the heart of Kerala—who hide secrets. From the African wife of an American in ‘Addis Ababa’, to the Indian making friends with Palestinians in the Jerusalem of ‘The Stones of Gazan’: these are people shifting between identities, pretending to be someone they’re not.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Benyamin’s stories span space and time: from Ireland to Solapur, from Kerala to Nainital. From a Roman ship sailing the high seas in the early years of Christianity to a taxi driver driving a passenger from Kochi’s Nedumbassery Airport. There are very exotic locales here and very mundane, familiar ones; people like us and people from another age, another strata.

And yet, Benyamin binds them all together into stories that speak to the common humanity in each of us. Here are the fears and the traumas that each of us, even if we have not been there ourselves, can relate to. The lost homeland, the ache for a life we have been wrenched from. The grinding poverty that will drive a person to desperate means. Ambition, even if for something so basic as not following a family occupation of picking pockets. Loneliness.

These stories are all uniformly good examples of the art and craft of storytelling; the plots are interesting, the characters memorable. The dialogue is very real.

But most of all, what shines through is the sheer depth of Benyamin’s understanding of human nature and his ability to depict it in all its nuances. One of the most impactful ways in which he does this is to leave things unsaid. Not all the i’s are dotted, not all the t’s are crossed, not every end is neatly tied up. Sometimes, as in the heart-breaking ‘Solapur’, there is enough said in passing for most readers to come to the same conclusion; in other stories, your guess may be as good as mine—and perhaps we could both be right. For instance, take the story of the Kashmiri forced to be a boatman in Nainital, ‘Javed the Mujahideen’: there is no conclusive end here, nothing you can pin down as the conclusion. Which, really, is what life is all about, too: messy and complicated, open to interpretation.

As the eponymous Alice of Alice in Wonderland (not Lewis Carroll’s but Benyamin’s) says, with profound wisdom: “No matter which story I say is true, you will still believe only the version that you choose to. It applies not just to stories—life, too, has this limitation.”

In the course of these stories, Benyamin touches upon various social and political issues: casteism, poverty, the exploitation of the rural poor by the urban elite. Racism, communalism, discrimination of myriad hues. All are woven deftly into these tales, in a way only a virtuoso like Benyamin can manage.