Language: We Are Like That Only

MANY OF MY FREQUENT readers will understand if I admit that I have long immodestly considered myself the inventor of the term ‘prepone’. I came up with it at St. Stephen’s in 1972, used it extensively in conversation, and employed it in an article in JS magazine soon after. ‘Prepone’, as a back construction from ‘postpone’, seemed so much simpler, to a teenage collegian, than clunkily saying ‘Could you move that appointment earlier?’ or ‘I would like to advance that deadline’ or ‘Please bring it forward to an earlier date.’ Over the years, I was gratified to see how extensively its use had spread in India.

But I was wrong. In keeping with the longstanding wisdom that there is nothing new under the sun, I was told by Catherine Henstridge of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), no less, that they have an example of the use of the word ‘prepone’ from 1913 in the New York Times. It didn’t catch on much in the West, but the proceedings of the 1952 Indian Science Congress reveal that other Indians thought along the same lines: ‘In Indian villages…demand for power can be preponed or postponed not only by hours but even by days.’ Clearly, the origin of ‘prepone’ has been preponed from 1972 to 1913, and I duly withdraw my clai0m to its origination. Mind you, I can still make a case, through frequent usage, for being somewhat involved in its popularization!

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Still, the persistence and survival of what is called Indian English (often with a sneer, as if to differentiate it from the Queen’s ‘propah’ English) deserves to be taken seriously. Our English, spoken without the shadow of Englishmen looming over us, is a vigorous and local language, which draws strength from local roots. If Americans can say ‘fall’ for autumn and ‘gotten’ for ‘have got’, though both are archaisms in England itself, why can’t Indians say ‘furlong’, ‘fortnight’, and ‘do the needful’, even if these have fallen out of use centuries ago in London? So many words in Indian English, including ‘prepone’, have stood up to the only test that matters—the test of time and usage. If enough people find a word or phrase useful, it is, to my mind, legitimate.

INDIAN ENGLISH IS a living, practical language, used by millions every day for practical purposes. I am not referring to expressions like satyagraha, namaste, or yogi, that have passed into the English language and are used exactly as they are in India. I am referring to the usage of English words differently in India from the Anglophone West. Many phrases we take for granted in ordinary conversation are actually quite unusual abroad—calling elders ‘auntie’ or ‘uncle’, for instance, or using the expression ‘non-veg’ to convey a willingness to eat meat. That doesn’t make them wrong, or even quaint. It just makes them Indian.

Some Indian English was created by our media and passed into regular usage—‘airdash’ (‘the chief minister airdashed to Delhi’) and ‘history sheeter’ (‘the police explained that habitual criminal X was a history sheeter’, i.e. that he had a long criminal record). Some, like my ‘prepone’, came from school and college campuses: ‘mugging’ (cramming hard for an exam, with much rote learning and memorization involved) uses a word that means two very different things to Americans or Brits abroad (a criminal assault by a robber, as in ‘She was the victim of a mugging in a dark alley’ or an elaborate and often comically exaggerated expression, as in ‘he was mugging for the camera’). When an Indian student tells a foreigner he was ‘mugging for an exam’, bewilderment is guaranteed. Yet it’s a vivid word that conveys exactly what is intended for every user of Indian English.

So the way Indians speak the English language is often distinctive but not necessarily incorrect. Some Indian Englishisms are merely translated from an Indian language: ‘What is your good name?’ is the classic, since all Bengalis, for instance, have a ‘daak naam’ that they are called by, and a ‘bhalo naam’ (or ‘good name’) for the record. But ‘what is your good name?’ is still the most polite form, in any Indian version of the English language, for finding out the identity of your interlocutor. ‘Is he your real brother?’ someone asks, not to accuse you of having imaginary siblings, but to differentiate this brother from a cousin, who is also referred to as a ‘brother’ by affectionate Indians.

Such cultural assumptions inevitably influence language. The widespread preference for—or at least acceptability of—vegetarianism in India makes Indian English the only language that uses the expression ‘non-veg’ for meat, fish, and those who consume them. The Indian arranged-marriage culture has also had its impact on our local English. Our matrimonial ads have created their own cultural tropes with expressions that only mean something in Indian English—‘wheatish complexion’, of course, and better still, ‘traditional with modern outlook’. Many ads require a prospective bride in India to be ‘homely’ (that is, home-loving and a good housekeeper) and to have ‘passed out’—not fainted or lost consciousness, as a Brit or American might assume, but graduated—from a ‘convent school’, in other words a school established by a missionary order, where the medium of instruction is English.

Some Indianisms are creative uses of an ordinary English word or phrase to reflect a particularly Indian sensibility— such as ‘kindly adjust’, said apologetically by the seventh person slipping into a bench meant for four. We have nothing to apologize about: we should defiantly celebrate their use as integral parts of our Indian English vocabulary. After all, ‘we are like that only’. And if you don’t like it, kindly adjust….

But acknowledging the legitimacy of Indian English and many of its formulations doesn’t mean that ‘anything goes’. Some things are simply wrong. The Indian habit of saying ‘I will return back’ is an unnecessary redundancy: if you return, you are coming back. I am more neutral about ‘revert’ as an Indianism for ‘get back’—a correspondent saying ‘I will revert to you by next week’ does not mean that he will convert himself into what you used to be, merely that he will issue a reply. Since the meaning is clear, objections to its use are unwarranted. But the desi practice of using ‘till’ to mean ‘as long as’ is simply incorrect English; it is wrong to say ‘I will miss you till you are away’ when you really mean is ‘I will miss you till you come back’! ‘I am staying Bandra side’ is not an acceptable equivalent of ‘I am living in the Bandra area’. And ‘back side’ for ‘rear’ causes much unwitting hilarity, as in signs proclaiming, ‘entry through back side only’. These can’t be justified under the rubric of Indian English. They are just bad English.

Indians are excessively fond of euphemisms: we would rather use a roundabout way of conveying an interest in a delicate topic rather than the direct word that foreign English speakers might. Thus we use ‘reduced’ as a synonym for losing weight (‘you’ve reduced?’). Your ‘intended’ spouse is your ‘would-be’ in India. A ‘loose character’ has dubious morals. Women speak of ‘chums’ for menstrual periods—‘chum’ is old English slang for ‘pal’ and must have been applied since these ‘chums’ are monthly visitors! Asking about ‘good news’ is a polite way of enquiring about pregnancy, and we speak of ‘issues’ when we mean ‘children’ (‘you’ve been married for ten years? Any issues?’ doesn’t mean ‘do you have problems in your marriage?’ but ‘do you have any children?’)

Cultural practices and assumptions are inevitably reflected in Indian English. You ‘belong to’ your ‘native place’ rather than simply being ‘from’ there, and your native place might be a ‘mofussil town’, that is in a rural or provincial area. If you’re not in town, you’re ‘out of station’. If you meet a lady who is elder to you, she is usually ‘auntie’ even if there is no blood relationship. Relationships matter in India and so terms are invented for which there is no English equivalent: thus your ‘co-brother’ is your wife’s sister’s spouse. There is even a term, going back to the days when travel beyond our shores was a rare and inordinately expensive privilege, for someone who’d come back after sojourning abroad: they were ‘foreign-returned’. And a unique Indian cultural practice gave us the expression ‘give me a missed call’, meaning ‘ring me briefly and hang up so your number shows up on my device and I will call you back at my expense when I am free’. The caller might be an impecunious relative who can’t afford to pay for the call, or merely a junior who would be seen as presumptuous otherwise: the ‘missed call’ addresses both these handicaps.

Then there are Indian formulations that have nothing to do with cultural sensitivities but simply reflect the way we apply certain words: you are sometimes required to ‘do the needful’; if you do it perfectly, you’ve achieved ‘cent per cent’, and your friend’s ‘thanks’ is met with ‘mention not’, rather than ‘don’t mention it’. We have a noun, ‘timepass’, for activities to while away one’s idle moments; we ‘take lunch’ rather than ‘have lunch’, see a ‘picture’ rather than a ‘movie’, and ‘put up’ somewhere rather than ‘stay’ there. What foreigners call sunglasses are ‘cooling-glasses’, ‘goggles’, or ‘glares’ in India. We ask for a ‘cold drink’ when we want what Americans call ‘soda’ (and the pompous refer to as an ‘aerated beverage’), though the drink may not in fact be cold.

Some Indian English expressions emerge from translating phrases in local languages, like ‘eating my head’ for ‘bothering me’, ‘sit on her head’ for ‘pressure her’, ‘I took his class’, or ‘I scolded him’. Others are more modern: an unfamiliar problem is ‘out of syllabus’, a good experience is ‘first-class’. Then there’s ‘rubber’ as a synonym for ‘eraser’. In the US a ‘rubber’ is what you use (in bed) to prevent a mistake; in India, you use it (in the classroom) after you make one.

Of course, some Indianisms are just awkward and arguably wrong, like ‘God promise’ and ‘mother promise’, to swear upon the divine or your mother, or saying ‘years back’ rather than ‘years ago’. The telephone has brought about other solecisms: ‘Hello, Ramu this side’ when you mean ‘Ramu here’, or the stranger on the line who says ‘Myself Salman, yourself?’ I’m tempted to reply ‘myself gone’, and ‘cut the call’—that is, hang up! n

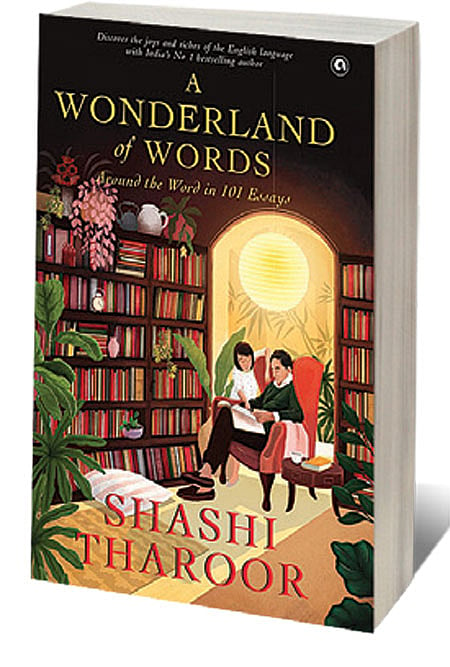

(This is an edited excerpt from A Wonderland of Word: Around the World in 101 Essays by Shashi Tharoor)