War for Peace

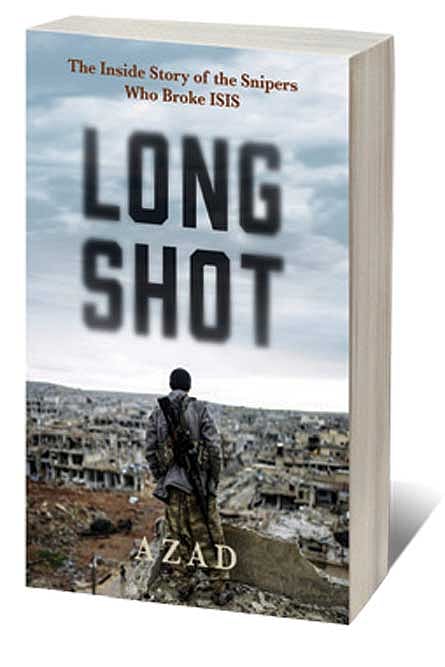

HIS FIRST NAME on his British passport is ‘Darren’ and his sniper name ‘Azad’. As a child from a Kurdish family who grew up in Iran in the 1980s, his parents used to call him ‘Sora’. Yes, we don’t know his real name yet, and we may never know. For his riveting book Long Shot, he has used the nom de plume ‘Azad Cudi’, for obvious reasons. After all, this is the story of the sniper he was from 2013 to 2016 in the war against the ISIS Caliphate.

For Kurds who, as a community, have for long been persecuted by their Arab, Persian and Turkish neighbours, Kobani is more than a territory. For them, it is part of a de facto area called Rojava, a constituent of the Greater Kurdistan they want to build to retain their identity and protect their interests.

Cudi, born and raised in Iran and conscripted into the army at 19, needn’t have fought this war to safeguard the interests of his people and of humanity. He was away in Leeds, making a living, enjoying time with his girlfriends in a new country that gave him political asylum after he fled the Iranian army when he realised he was part of a special force meant to kill his own people, Kurds, whom Tehran considers terrorists. His weeks-long escape from Iran to the shores of UK via numerous modes of transport—cars, vans, trucks and boat—was obtained through a bribe his family and friends had paid. He had no reason to go back to the hellish life of Kurdish soldiers fighting for autonomy and freedom of their people.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

That was until he came across books by the jailed Kurdish leader of Turkish descent, Abdullah Öcalan, still confined to an island jail off Turkey as the sole prisoner. While in captivity, the Kurdish leader wrote many books that blew Cudi’s mind, especially those on Jineology, feminist thoughts, by the man known to his admirers as Apo. Öcalan not only rejected the patronising attitude of Western commentators who he thought were fatalistic in their arguments about the Middle East, but he also rued the unequal status of women and wanted to see them as equals, which, Cudi found, was most evident in Kurdish armies. According to Apo, ‘housewification’ was the oldest form of slavery.

Cudi, by then Westernised, came under Apo’s spell. That was how after a tour of Kurdish areas more than 10 years after he fled Iran, Cudi finally decided to bid farewell to his foster country and join his brothers-in-arms to fight the ISIS to the finish. He was sent to Kobani for several eventful months to assist the forces as a sniper and he played his role to perfection. Long Shot is a story of that resistance and his comrades, men and women, who fought alongside in the most miserable war conditions.

In fact, the ISIS, which had already captured hundreds of towns and villages, sent 12,000 men armed with state-of- the-art weapons to Kobani, reflecting its strategic importance. Kurdish forces lined up their best fighters to defend it with 40-year-old Kalashnikovs and other rifles that often jammed. But every soldier on their side, Cudi says, had this thought: ‘If ISIS captured [Kobani], they would cut Rojava into two and take over a ninety-kilometre stretch of the Turkish border over which thousands more foreign Jihadists could cross. They would also crush our dream of building a new democratic and free society in the Middle East.’

Here is where Cudi invokes Vasily Zaytsev, made famous by the movie Enemy at the Gates starring Jude Law as the legendary World War II Soviet sniper who stopped the Germans, until then considered invincible, in Stalingrad. Cudi writes: ‘By committing so many men to Kobani, the Jihadists unwittingly gave us an opportunity to defeat them. And as Vasily Zaytsev had shown in Stalingrad in 1942, when the enemy enters the city, a single unblinking sharp- shooter can keep an entire city in the dirt and change the course of a war.’ For Cudi the sniper, Kobani was a Stalingrad moment in the anti-ISIS war.

Before plunging into months-long war after which he, then in his early thirties, returns weighing as much ‘a 13-year-old would weigh’, he learnt first-hand from Yazidi men and women the brutalities of the ISIS. According to an ISIS pamphlet he came across, it was permissible to have sex with a pre- pubescent girl if she was ‘fit for intercourse’. It was also legal to buy, sell or give Yazidi females since, ‘as unbelievers and sub-humans, they were merely property which can be disposed of’. All this also applied to children that, Cudi says in his book, resulted ‘from the Jihadis’ industrial- scale raping’. The strategy behind this savagery, they all knew, was to force the enemies to flee. But Kurds wouldn’t. They had a women’s militia named YPJ and a men’s named YPG, and both would fight together, shoulder to shoulder.

In Long Shot, Cudi gives tips on how to be a formidable and skillful sniper, patience being the most coveted virtue. Still, when he started off, it was difficult to kill and nightmares stayed on for days and weeks. He talks about the ‘fragility of their endeavour’—which none of the warriors talked about among themselves. But soon, in the thick of a no-holds-barred war, he lost his sense of fear, the fear of death. Every day, people whom he knew died and had to be carried away to be given a decent funeral. Death began to lose its sting.

For a veteran, Cudi gets philosophical at times—and naturally so. We have heard of Hemingway talk of the fragility of wars before: ‘In a modern war, there is nothing sweet not fitting in your dying. You die like a dog for no reason.’ Was there a reason then for death in pre-modern wars? Maybe not. Cudi treats all wars alike, saying, ‘There is no predictability to war, no logic to death, and no arguing with any of it. Death took, tirelessly and carelessly. You couldn’t explain it, and to discuss it was pointless. You could only accept it.’

Several writers, including those of the stature of Svetlana Alexievich, have written about the unending traumas of war. Cudi, a sniper, is a notable addition to that league because he talks not only about the heroism of the victorious Kurdish fighters against one of the world’s most dangerous organisations, but also about life after the war. He is proud of his feats as a sniper, but he also wants to see results and a bright future for those whom he had fought for.

Cudi is now back in Britain, where he finished writing the book for which he had extensively interviewed Kurdish fighters and academics elsewhere. For someone who had been an entrepreneur in the UK and then a diasporic journalist in Sweden before he volunteered as a sniper, he is learning to cope with the wounds and the losses of the war, and has got back to his favourite sport: ice-skating. But as he says, ‘For now, like forty-five million other Kurds, I am still waiting for a home.’