Vikram Seth: Still Suitable

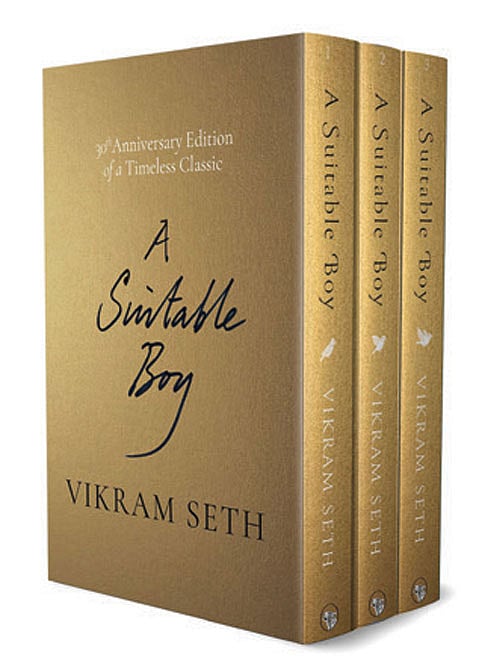

MARRIAGE, MORALITY, AND social change. The concerns of Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy (1993) are resolutely old-fashioned, as is the manner of its narration. Thirty years after publication, does the book—released recently as a limited edition three-volume box set by Speaking Tiger (1,584 pages; ₹1,799)— remain relevant and enlightening?

Let’s start with a comparison. Halfway through the novel, one of its many characters complains that she has a headache as huge as Buddenbrooks. That’s an impish reference to a book that can be juxtaposed with Seth’s own work, which happens to be twice the size.

Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks has sometimes been called one of the last great 19th-century novels, though it was published a year after the century’s end. It’s a multi-generational epic that traces the rise and fall of a merchant family in the German city of Lübeck and, in doing so, encompasses weddings, births, deaths, business, the fates of siblings, dinner parties, and domestic life. So far, so suitable.

More than a hundred years later, what resonates is the theme of a bourgeois family’s decline and the way Mann’s characters embody the conflict between tradition and modernity. As for A Suitable Boy, it starts with a playful sonnet in which Seth asks the prospective reader to “buy me before good sense insists / You’ll strain your purse and sprain your wrists”. Is this still good advice?

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

To begin with, Seth’s prose is easier on the eye than Thomas Mann’s. Both juxtapose humour and seriousness, but the former employs a lightness of touch and gentle irony that is close to Austenesque. The use of wordplay, doggerel, lyrics, advertisements, and cut and thrust of the dialogue remain delightful.

Buddenbrooks also contrasts inward achievement with outward success. This theme is present in A Suitable Boy too, and it is one that remains contemporary. Characters seesaw between living up to familial expectations and following their own paths, with mixed results.

At one stage, this is spelt out by Amit, the young scion of Calcutta’s illustrious Chatterjee family. “Why earn more than I need?” he thinks. “If I take up practising law, apart from boring myself and being irritable to everyone around me, I will achieve nothing of permanent worth. I will be just one among thousands of lawyers. It is better to write one lasting sonnet than to win a hundred spectacular cases.” Fortunately, he’s in a position to make the attempt.

Above and beyond these aspects is the book’s audacious ambition. A Suitable Boy essentially takes a marriage plot—involving love, courtship, social assumptions, and the pursuit of happiness through wedlock—and expands it to encompass nothing less than the condition of a large swathe of India in the 1950s. This Encyclopaedia Sethica contains multitudes.

In a 2018 interview, the author himself said about the writing of the book that instead of being just a love story, “A Suitable Boy became a story about economics, politics, a larger vista, Indian life, and the fact that our lives are determined by macro as well as micro forces.” A fruitful way to look at it, then, is to view the characters’ choices as arising out of mainstream narratives, for better or worse.

A reflection of the task that Seth set himself comes in a passage in which the occasionally voluble Amit, composing a novel of his own, says that the performance of a raag resembles the sort of book he was trying to write.

“You take one note and explore it for a while, then another to discover its possibilities,” he explains, “then perhaps you get to the dominant and pause for a bit, and it’s only gradually that the phrases begin to form and the tabla joins in with the beat... And then the more brilliant improvisations and diversions begin, with the main theme returning from time to time, and finally it all speeds up, and the excitement increases to a climax.” That sums it up.

The 19-year-old Lata’s quest for a husband is the motor of the plot, which comfortably chugs along and carries in its wake the sagas of others such as Maan and Saeeda Bai, and members and associates of the Mehra, Khan, Kapoor, and Chatterjee families. Through their journeys, they bring to life the cultural and social environment of a newly independent country looking over its shoulder at the scars of Partition even as it grapples with the future.

The characters remain compelling because they are portrayed with virtues and flaws and without moralising. Seth glides from one consciousness to the next, extending the courtesy of attention to even minor characters by showing us idiosyncrasies of thought and behaviour. This is especially evident in the novel’s many set pieces, from festivities in Brahmpur mansions to meals in Calcutta apartments.

The scene-setting, too, is elaborate. A description of Brahmpur’s high street, for instance, mentions bookshops, general stores “such as Dowling & Snapp (now under Indian management)”, tailors, a shoe shop, an elegant jewellery store, restaurants, coffee houses “such as the Red Fox, Chez Yasmeen, and the Blue Danube,” and two cinema halls, “Manorma Talkies (which showed Hindi films) and the Rialto (which leaned towards Hollywood and Ealing)”.

Equal attention to smaller details further enlivens the book. The buttering of toast; the brandishing of a walking stick; the crafting of hand-made greeting cards; the care of gardens: these and more play their parts in creating vivid tableaux that make the book evergreen.

Political and occupational contexts are similarly well-etched and wide-ranging. Some characters take part in legislative debates and local-level politics; others absorb the intricacies of shoemaking or classical music; and yet others analyse the minutiae and impact of land reform acts. At such times, considerable research is evident, yet for the most part, it is lightly worn.

Re-reading some passages all these years later also reveals the deep roots of current national scenarios. In one section, we’re informed: “The economy, under-planned and over-planned, lurched from crisis to crisis. There were few jobs waiting for the students themselves after graduation. Their post-Independence romanticism and post- Independence disillusionment formed a volatile mixture.” The volatility persists.

Scuffles lead to riots outside temples; suspicions of other communities and castes result in flare-ups in rural and urban areas; and the roles of Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhai Patel, and others are avidly dissected. At one stage, Lata receives a letter from a friend during the run-up to a local election: “Everyone is involved in pushing himself forward, spouting slogans, making promises, and not bothering about how these promises are to be paid for, let alone implemented. Even sensible people seem to have gone off their heads.” The past is never dead, as William Faulkner said, it’s not even past.

Three decades since it was published, A Suitable Boy unwittingly shows how inherited beliefs, cultural traditions, social inequalities, and unresolved conflicts tragically linger on to shape individual destinies. Nehru, who makes a brief appearance in the novel, thinks: “Now, everything is muddied. Old companions had turned political rivals. The purposes for which he had fought were being undermined, and perhaps he himself was to blame for letting things slide so long.” Little did he know how far this argument would stretch.

Seth’s magnum opus stands out after all these years because of his

skill in using 19th-century realistic techniques to depict relevant incidents and attitudes from decades ago. This deeply humanistic approach makes the novel much more than about the search for a suitable boy. It’s also about the search for a suitable nation.