Valour Undimmed

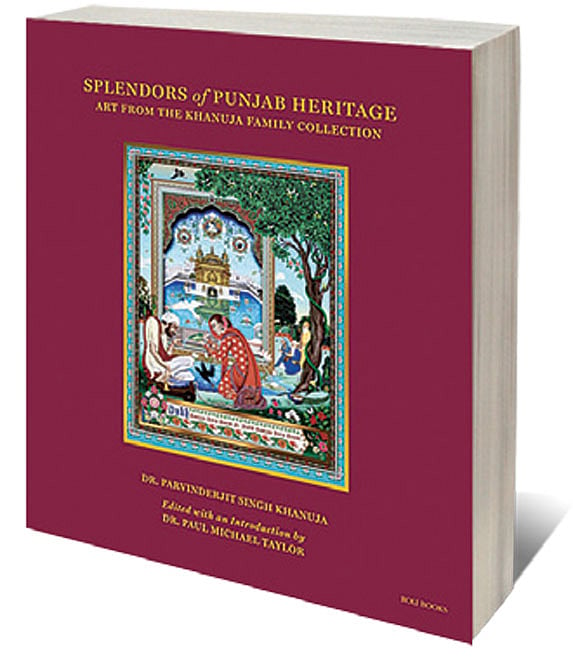

THE BOOK, SPLENDORS of Punjab Heritage, is by all standards an extraordinary journey into the past of the Sikh community aided by art and artefacts, which define the history of the Sikhs collected by the family of Dr Parvinderjit Singh Khanuja, an oncologist who has been living in Phoenix Arizona, US for the last 30 years.

There is now a permanent Sikh Art gallery at the Phoenix Art Museum devoted to highlighting the contribution of the people who call themselves Sikhs, adherents of Sikhism in all its manifold variety. The volume under review acts almost like a catalogue for a portion of the exhibits, while also channelling the spiritual dimension of Sikhism as propagated by its revered teachers known as the ten gurus, or Sants and finally enshrined in its sacred book, known as the Guru Granth Sahib.

Originally from the Punjab, the region defined by the five major tributaries of the mighty Indus river bordering the north-western flank of the Indian subcontinent, the Sikhs have allocated upon themselves the role of warrior-guardians standing at the gates. Towards the end of the volume, Ajeet Caur, a noted writer whose daughter Arpana Caur has contributed some of the more striking contemporary images of Sikh personalities and social movements in India, describes the spirit of what it means to be from the Punjab; “Punjabiyat epitomises the spirit of oneness, gender equality, hard work (kirat karo), sharing (wand chako), democracy, upholding of human rights, and spiritual quest.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

There is also a term, “Chardi Kala” translated as “eternal optimism,” which defines the warmth of the people of Punjab living in what has been known as the Granary of India. The last illustration actually depicts an amazing composition of the Farmer’s Agitation of 2021 by Sukhpreet Singh. There is also a deeply moving image, Ghost Trains of 1947 by Rupy C Tut detailing the desecration of the chador of humanity that once united both sides of the Punjab.

Let us also underline that Sikhism and the contribution of its adherents to the culture of the Punjab, as suggested by the title, is by no means exclusive to them. Indeed while some portions of Ajeet Caur’s narrative touches upon the horror that was visited upon the Sikh community in 1984 following the storming of the most sacred of their precincts at the Golden Temple in Amritsar; and later in the year, the brutal and merciless suppression of the community following the assassination of the Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi by her two Sikh bodyguards within the precincts of her home, it is pertinent to wonder whether the volume devoted to the arts is also a form of proselytising.

Or to quote from one of the texts, Khanuja like so many other disenfranchised persons from the countries of their birth might echo the words of the tenth guru, Gobind Singh (1666-1708) when he wrote to the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb: “When all other methods fail, it is proper to hold the sword in hand.”

There’s a wonderfully evocative image of Guru Gobind Singh by The Singh Twins, as the UK-based artists are known, that shows him sword in hand in the main inset with small cameos from his life. Prime amongst these is a bowl of water and sugar that he mixes with a double-edged dagger and offers to men of different castes to become a part of his Khalsa, or revolutionary path.

Khanuja wields both sword and pen with equal felicity. In this he is ably assisted by the book’s editor Paul Michael Taylor, an associate at the Asian Cultural History Program, Smithsonian Institution.