‘There was no telling where a new bud might sprout’

MY FAMILY LEFT Sirsi and moved to Dharwad in 1952. I lived there for six years, until I moved to Bombay in 1958. My first two years in Dharwad were spent at the Basel Mission School, but from the moment I stepped into the city, my eyes were firmly set on what was certainly the most magnificent as well as the best-known building in the area: Karnatak College.

In 1952, India had not been reorganised linguistically, and the districts of Dharwad, Belgaum, Bijapur and Karwar were part of the Bombay Presidency. These four districts stood apart in a huge administrative unit that sprawled from the northern borders of Mangalore district to Gujarat, because these were areas where Kannada was spoken. The rest of the Presidency was dominated by Marathi and Gujarati. Bombay was the capital of this Presidency, but Kannada was not heard in the city except in the homes of those who had moved there for education or employment. Even sophisticated Marathi literature of the period is replete with mocking references to Kannada, calling it crude and uncouth. North Karnataka, as these four districts were known, was remote from the capital and an economically neglected area. Culturally, it was dominated by the Marathi language. Aayi, my mother, often lamented that, by accepting the transfer to Sirsi, Bappa had deprived us of the rich and vibrant culture of Maharashtra and Marathi.

It was not just that North Karnataka was remote from the political centres of Bombay and Poona, it also lived a life sundered from the princely state of Mysore, which considered itself the acme of pure Kannada culture. Even the spoken idiom of North Karnataka was considered rough and uncivilised compared to the polished court language that emanated from Mysore. The district of South Kanara—Mangalore—which formed a part of the Madras Presidency, had benefitted from the attention paid to it by Christian missionaries, who built excellent educational institutions there as well as the rudiments of industrialisation. While banks originating in North Karnataka had sunk without a trace, the four from South Kanara—Canara, Corporation, Vijaya and Syndicate—had gathered strength and would go on to become banks of national importance.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Isolated from Mysore and South Kanara, North Karnataka had found a local cultural centre in Dharwad. The city was on the western edge of the Deccan plateau, around 150km from the Goan coastal strip, situated on an outcrop before the Western Ghats plunged down to the sea. It had, therefore, a temperate climate. The British had built many educational institutions there, and Dharwad was admired as a place suitable for retired government servants, college students and poets.

In the Marikamba School in Sirsi, we had been brought up to believe that literary figures were endowed with divine grace. And Dharwad was bursting with such celebrities. One day, while I was still at the Basel Mission School, my Kannada teacher invited a few of us students home for tea. While we were animatedly discussing the state of Kannada literature, a gracious old man in flowing clothes and with a resplendent beard walked in, sat down, chatted with us and left. It turned out to be Aluru Venkata Rao, one of the founding figures of modern Kannada literature. I was so thrilled by the encounter that I went home and wrote a poem about him. Later, I met several such revered figures (though none of them again inspired a poem). In fact, the high density of poets in Dharwad was not particularly conducive to a young man aspiring to be a poet. The cliché was that the city’s population was divided into two species: poets and critics. Another saying went: ‘If you stand in a corner and randomly fling a stone in Dharwad, it will land on the roof of a poet.’ To which a local poet Chennaveera Kanavi added, ‘The stone thrower is invariably a poet too.’

One day, the writer VK Gokak came to our school to judge a poetry contest. He was also the principal of Karnatak College, where I hoped to study, and so I observed him intently. Since coming to Dharwad, I had visited Karnatak College several times, gazed longingly at the building, and thrilled at imagining myself in its corridors. The college building had originally been constructed by the Madras and Southern Mahratta Railway for its offices, but a governor of Bombay had been generous enough to acquire it for the education department. It was a magnificent structure in redbrick and steel. The arches of its elegant façade, the wide corridors and spacious classrooms, the grand steps at the front of the college, the spiral staircases at the ends of corridors, all gave it a grandeur in keeping with the stature of the college.

Gokak’s personality matched the college he was principal of: he was a tall man who walked with a long stride and a slight stoop; he had a smiling countenance and a deep, somewhat nasal voice. And in my eyes, he possessed all the glamour of a leading literary figure. As if this weren’t enough, his academic prowess shone about him like a halo: he had studied English literature at Oxford and been awarded the rare ‘congratulatory first’. So, it could be said that he had surpassed our British rulers at their own literature.

What made the deepest impression on students was Gokak’s boundless enthusiasm for teaching. Since he taught at all stages of the four-year degree course, every class had the opportunity to interact closely with him. As a result, he too had some idea about what was going on with the students in different classes.

Soon after I joined college, I spoke to him in the corridor after a class. ‘I write poetry,’ I told him. ‘I want to understand modern English poetry. What should I read?’ He took me to his office and said, ‘Sit. Write this down.’ I sat in front of him, practically trembling with eagerness. He said, ‘Had you asked this question to anyone else, they might have asked you to read TS Eliot. He’s a good poet, of course. But he’s a difficult poet. Don’t start with him.’ He gave me the names of WH Auden, Stephen Spender, Cecil Day-Lewis and Louis MacNeice. I ran at once to the college library.

The evolution of my artistic sensibilities seemed to begin the instant I set foot in college. I could experience this myself from day to day. The novel I had read and adored a week ago would start to feel ordinary. ‘At last, I have written a good poem,’ I would congratulate myself, but the same poem felt childish after a few days. It was the kind of feverish stimulation that the poet Adiga described as ‘Everywhere the hand extends – a switch, a switch.’ Going to the library became a cause for anxiety. It was like stepping into a minefield: there was no telling where a new bud might sprout, when a lightning bolt might strike.

NE DAY, A classmate held out a book and said, grumbling, ‘I borrowed the book thinking it would have a good story, but this…’ It was BC Ramachandra Sharma’s Elu Suttina Kote. I sat down at once to read the poems. On another day, I was looking at books through the glass pane of a bookcase when I saw on a spine the name Frost. I drew the book out of curiosity, and was immediately transported by the poems. Robert Frost remains one of my favourite poets to this day.

Similarly, I began to read a book called A Key to Modern British Poetry after it caught my eye in the library. It was by a then-unknown writer named Lawrence Durrell. He wrote that the scientific advances of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries had changed what lay at the heart of poetry, and that it was impossible to write poetry any more without responding to the world that science was opening up. He described with examples how poetry had been transformed by the work of scientists like Einstein, Freud, Darwin and others. Durrell would go on to make a name for himself as a novelist. When I was at Oxford, copies of The Alexandria Quartet were invariably found on every student’s bookshelf. But I have not to date met anyone who has read or even heard of A Key to Modern British Poetry. In addition to its bold ideas, I also benefitted from the writers it quoted. It brought to my attention Eliot, Dylan Thomas, Freud and others, and made them part of my consciousness.

My four years in college can be bookended by two great poems. In the first year, I had read the poems in my English textbook even before classes began and marked the ones I had found difficult. So, when Gokak asked in class, ‘What poem should I teach today?’ I immediately said ‘Kubla Khan’ (for which my classmates cursed me later). Gokak nodded gravely. He started with Plato, expounded upon Beauty, Truth and Goodness as philosophical concepts, and went on to explain how the early nineteenth-century Romantic poets incorporated these ideas into their work. ‘Kubla Khan’ had come to Coleridge in an opium-induced reverie, and Gokak unlocked for us the magical world hidden in it. I grew obsessed with the poem after he taught it. In the next three years, I translated it thrice into Kannada.

When I was in the fourth year, my friend Kitti—Krishna Basrur—who was in the MA course, brought news that VM Inamdar was about to teach ‘The Waste Land’ in his class. I had begun looking up to Inamdar when he taught us The Mayor of Casterbridge. He brought Hardy’s Wessex to life as if it were all happening on a stage in front of us. The story, in which tragic characters grapple with fates that toss them about, made my hair stand on end. In his classes, one had a chance to feel the throbbing heart of a novel. Gokak, on the other hand, had a greater affinity towards poetry. I don’t recall ever having heard him speak of modern novels with any enthusiasm. His sensibilities, too, were of the Romantic period, and he regarded Shelley as the greatest of poets. Inamdar’s teaching of ‘The Waste Land’ took me by the hand and led me to the modern. I recalled Gokak’s warning that Eliot was a difficult poet. But now, he was mine. Later, Kitti, Aurora and I sat in a

corner reading ‘The Four Quartets’, savouring it line by line.

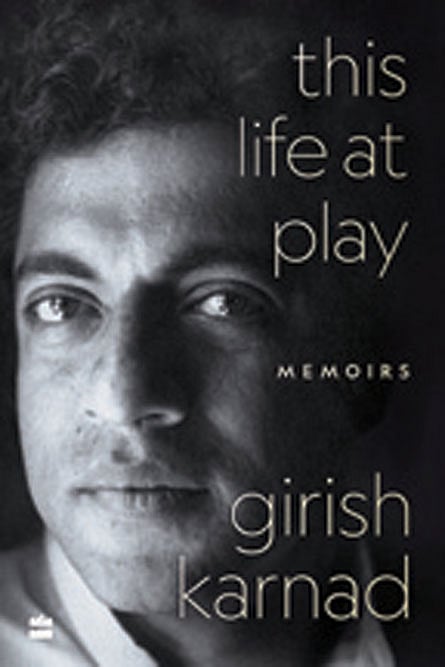

(This is an edited excerpt from This Life At Play: Memoirs, translated from the Kannada by Girish Karnad (1938-2019) and Srinath Perur | Fourth Estate | 320 pages | Rs799)