Theatre of the Everyday

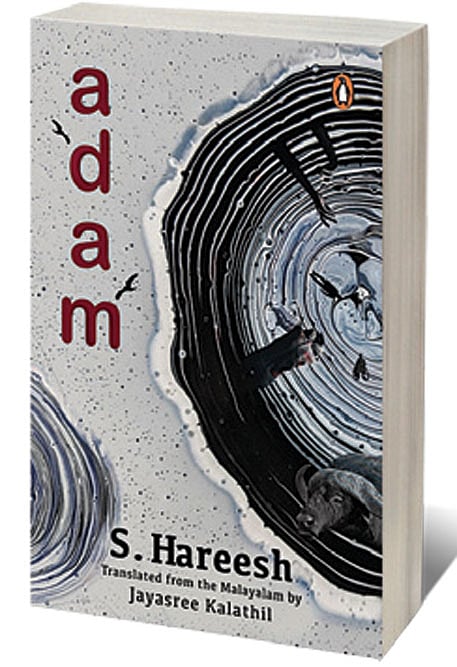

AMONG THE MANY electric passages in Adam, a collection of stories by the Malayali writer S Hareesh (translated from Malayalam by Jayasree Kalathil; Vintage; 179 pages; ₹ 499), my favourite came at the end, in a tale called ‘Night Watch’. An old man has died and his long-time enemy has come straight to the house, apparently to help with the last rites but also to gaze upon the dead body with some satisfaction. Soon after this we are told of a public confrontation between the two adversaries a week earlier—a verbal battle that grew to seemingly apocalyptic dimensions, with abuses so rich and profound that the story’s narrator can’t even specify what they are.

“Sankunniyaasan uttered a phrase that annihilated all moral values in the collective mind of the audience,” we learn—and then “Madhavan delivered a response that could not have been possible even in the farthest reaches of

a nightmare.”

Breathtaking in its playfulness and intensity, this passage shows a distinct aspect of Hareesh’s work—the ability to work in the epic mode and the realistic or mundane one at the same time. As the episode builds, one thinks of warriors in ancient literature—say, Bhishma and Parashurama in the Mahabharata—assailing each other with world-destroying weapons like the Brahmastra. (“They began with a few choice but ordinary words, but the sparks from these spread until a forest fire of larger and meatier words blazed […] the enemies turned into wizards who conjured up new and imaginative obscenities, slicing and splicing existing ones.”) And yet, one never forgets that this is a real setting involving two aged, mundu-clad men who have just participated (without speaking to each other) in a card game behind a paan shop.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Somehow the much-used descriptor “magic realism” doesn’t seem an adequate description of this effect; the events being described in most of these stories aren’t mystical or otherworldly (with one or two possible exceptions), but the nature of the telling creates that impression. Or maybe something about the setting lends itself to poetic exaggeration.

There are unexpectedly funny little moments in all the stories. In ‘Kavyamela’, when a blind man revisits a large rock off which he had once fallen, we are told that he “walked up to the rock and sat on it as if in vengeance”. Dogs in heat are described as flirting or canoodling with each other. Though death is a theme that runs through this book, the treatment can be simultaneously comic and tragic. For instance, in ‘Magic Tail’, a young woman has to transport her father’s dead body a long way home; it’s a sad occasion and her grief is genuine, but somehow, in an intriguingly matter-of-fact way, the journey also becomes an occasion for sexual banter—and possibly more—between her and the acquaintance who is driving her (in a Maruti Omni converted into a hearse).

Elsewhere, an ambiguity surrounds the very nature of death. “I’ve finally defeated you,” thinks Sankunniyaasan, looking at Madhavan’s corpse in ‘Night Watch’—but is there more to come? Will they continue their eternal battle in the afterlife? Two of the most haunting stories in this collection imply a blurring of the line between living and not-living. In ‘Alone’, a man on his way home from work gets off the bus and finds himself on a dark, deserted path, not sure of the direction he must walk in—and soon realises that the reason for his fear and dislocation is that it is the first time he has been completely alone. This strange, compelling tale is open to interpretation—perhaps what is being described is the loneliness of the afterlife. (“What if, in other places, the sun had risen several times? What if this place would never again see the light of day? What if eons had gone by since his wife and children had stopped crying for him?”) A similar tone is achieved in ‘Death Notice’, which describes the deaths of non-human creatures—a cow dies after a childbirth gone badly wrong, new-born puppies are destroyed, a turtle is caught and cooked—and then gives us two men playing a macabre game involving newspaper obituaries, before a final twist in the tale.

Then there are the two longest pieces, ‘Maoist’ and the title story ‘Adam’, both of which centre on animals but are about the intersection of many worlds: human and canine, human and bovine, and of course the divides and conflicts within our species. ‘Adam’ can loosely be summarised as a story about four puppies from the same litter, each living out a different destiny, but that wouldn’t begin to convey the full scope of this tale. One pup, who becomes Victor, ends up working as a police dog, the pride of the force for years—though even this doesn’t preclude a sad end. Another, Candy, leads a comfortable life until her master gets married to someone who doesn’t like dogs. Yet another, Arthur, gets a new name after being kidnapped. Their circumstances change over time, and the narrative takes the shape of vignettes, one flowing into the next, as if the narrator is a celestial bookkeeper recounting the highlights of various lives. In another writer’s hands it would seem like the animals are being used only as metaphors for human struggles, but that isn’t the case here—the dogs are dogs, what happens to them feels organic and truthful, and in any case we are also privy to the stories and shifting fortunes of the actual humans in the story.

A similar effect is achieved in the brilliant ‘Maoist’, perhaps the most well-known story here, being the seed of the acclaimed 2019 film Jallikattu (which was scripted by Hareesh and selected as India’s entry to the Oscars). ‘Maoist’ uses the framing device of two runaway buffaloes for a funny, hard-hitting sociological study of a village and its class politics. As the hunt gathers pace, we meet characters who represent different hierarchies and types. The family of Varky the butcher has the nickname ‘Kaalan’ not because Kaalan, the God of Death, rides on a buffalo, but because of the clan’s extraordinarily long legs (or “kaalu”), which makes them instantly identifiable. The politics of meat-eating and packaging are revealed (local dignitaries get meat that has been cut into fine, neat pieces; lesser customers get carelessly hacked “seconds”.)

From landowners to rowdies to Communists, everyone is affected.

A young man posts a video of the buffalo chase on Facebook, leading to “shares” and astonished comments from around the world.

Here again, Hareesh’s prose often operates in a grand meter without losing sight of the everyday: a passage about how the pursuit causes ebbs and flows in different people’s destinies begins with the showy line, “Presently, as though ordained by God himself, the land witnessed the complete fall from grace of two of its prominent personages…” To watch Jallikattu after reading this story is to marvel at how these thirty-odd pages can create such an elaborate universe, within the borders of a small Keralite village—while also spawning a visually striking film that has long silent passages.

Reading Hareesh’s novel Moustache (originally Meesha; also translated into English by Jayasree Kalathil) a couple of years ago, I loved the scope and ambition of the narrative, but also felt it was too exhausting to take in all at once; that it may have worked better as a collection of linked but standalone short stories. The stories in Adam suggest that Hareesh is in his element in the short-story format. These rich, imaginative tales need more than one reading to fully process the ways in which they blur the line not just between humans and other forces of nature, but also between life and death, dreaming and wakefulness.