The Urban Sketcher

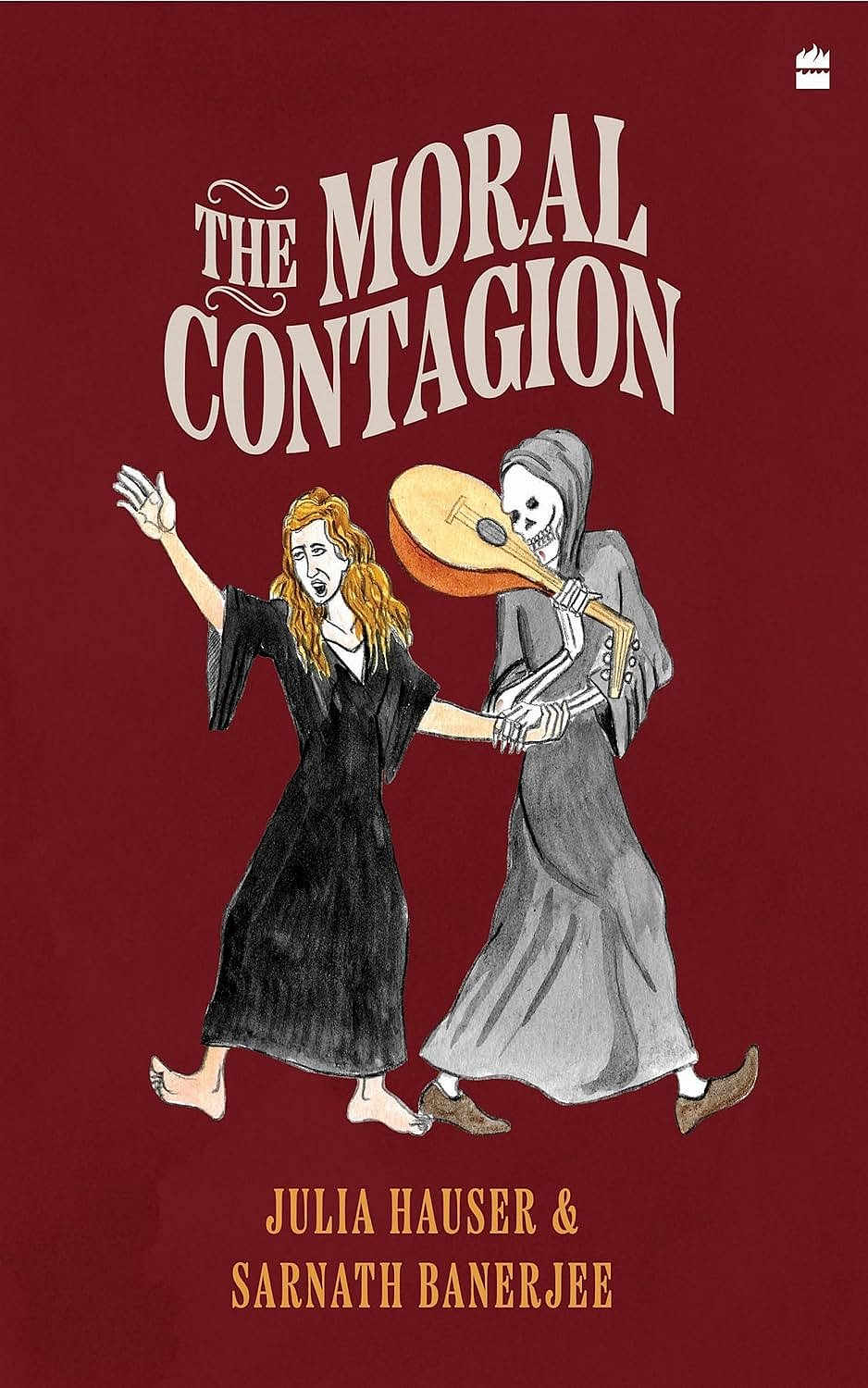

THIS MONTH WILL MARK four years since WHO declared Covid a pandemic. With the benefit of hindsight, and ample stocks of tetracycline, we can look back at three great waves of the plague which engulfed the world, generating a commonality of experiences. Written by Julia Hauser and with art by Sarnath Banerjee, The Moral Contagion (HarperCollins; 140 pages; `699) looks at not the biology of the pandemic but its morals.

I ask Hauser how the collaboration began. She explains her interest began during the lockdown, starting from the question of if and how Covid would change societies, and then leading to how pandemics in the past had changed morality.

The dread that a plague announces is because of its unique signature, much like how a serial killer has a distinctive twist in their killing method. Over nine chapters and 1,400 years, we journey from Emperor Justinian’s Constantinople to Gandhi’s South Africa, with stops at Aleppo and Hong Kong. The book was conceived from the start with Banerjee’s art, whose illustrations accompany and accentuate the text, ranging from full-page splashes that set up the scene, to others which intermingle with the text, showing some telling details. The hierarchy of colonial Hong Kong is reproduced with the Chinese coolie at the base of a hill and the white masters above.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The numberless funeral pyres of the second wave are shown with bright crayon strokes. Kitasato Shibasaburō, who was the co-discoverer of the bacterium along with Alexandre Yersin, but was discreetly written out of history, gets a full-length portrait in recompense.

Banerjee’s style has been described as “surreal…combining humour and realistic drawings with subtle caricaturing elements.” His work uses a dense collage effect achieved through sketches, photographs, old movie posters, graffiti, and advertisements, all layered with precision.

He is not a fan of what he calls the meme style of writing/drawing. He explains, “You are not drawing things keeping in mind that, oh, that image will be iconic.” The idea of the iconic image did not exist, he adds, “So, it is Test cricket. You just play good cricket.”

BANERJEE AFTER A long stint in Germany has moved back to India, teaching at the IIT in Gandhinagar. After the cosmopolitan elegance of Berlin, and the frenetic energy of Delhi, isn’t it on the rustic side I ask? Not at all. “Social over-simulation is the death for the comic artist,” he declaims. “A dull, monotonous life is necessary for art practice”.

Delhi and Calcutta got a book—what about Berlin? He has just completed a new book, “based on collisional narrative”. He explains, “Our modernity, which is a kind of imperfect, mila-jhula modernity” and when it clashes “with a very organised modernity, or a very well-studied and a very well-framed modernity, of the West,” “when these two collide with each other, then a certain narrative forms”. And this is not a diaspora narrative he hastens to add, explaining, “Berlin took a long time. Took 14 years for me. The first two years you are very enthu. You think that it’s full of promises. There are so many things to discover. After two years comes a plateau and that’s when you start realising that, arrey these are very different people.”

Banerjee is snazzily dressed in a Mao jacket, and black shades, giving him the air of a 1970s villain about to make a threatening phone call to Shashi Kapoor. We are in a restaurant and are washing down haleem with red wine. Banerjee’s narrator in his debut graphic novel Corridor declares, “On good days I feel like Ibn Battua, on bad days I don’t. But on bad days I think of good days when I feel like Ibn Battuta and the bad days don’t seem so bad.”

Banerjee utters an unprintable expletive. “Apne bhi soch.” He is addressing an absent critic who reviewed Corridor, 20 years ago. Since then, he has come out with The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers (2007), The Harappa Files (2011), All Quiet in Vikaspuri (2016) and Doab Dil (2019). But he still remembers the first negative review. Every writer does. The review was a long list of Western graphic novels that the reviewer had read, and how Corridor wasn’t one of those. “A colonial subject,” he says of the reviewer shaking his head.

We are in an old Hyderabadi bungalow turned into a café. Despite being midnight, it is packed, and we somehow manage to secure a coveted outdoor table. The waiter is from Asansol and Banerjee shifts to rapid-fire Bengali. He wants tea, as the hour is late, but the waiter counter-offers cascara, made from dried husks of coffee cherries.

Banerjee explains, “When you bring out your first comic book, there is always an over smart reviewer.” “And they often just say this is not that this, and talk about Eddie Campbell, about Maus, about Robert Crumb, Alison Bechdel. But they don’t talk about what is in there, what is that makes it special.”

Banerjee’ s Corridor kickstarted the Indian graphic novel ‘scene’, giving young artists and writers confidence that their own streets, their own conversations mattered, that it didn’t have to be always Gotham or Metropolis. Corridor gave Indian readers a cast of characters revolving around Jehangir Rangoonwalla, a philosopher-second-hand bookseller operating out of a corridor in Connaught Place. It captures the terroir of a time, the long 1990s, and is a relic from the pre-Photoshop era, as Banerjee points out, the speech bubbles were handwritten and cut out with scalpels and pasted onto the panels containing the art.

“So, it took a while for us to come out of that shackle, this international reading, therefore reviewing, comparing or calibrating against all that, a real under confidence in your own local context, local reality.” Banerjee adds that it “almost exclusively had got generous reviews”, but “that time it mattered a lot, that time it really hurt but now, you know, it increasingly doesn’t”.

Have you revisited Corridor I ask? Not really he says. The “drawings are very kachcha but it has josh, the primal energy which can’t be replicated”.

Finally, Banerjee orders a do-it-yourself Americano, two shots of espresso with hot water by the side. It is blacker than sin. We are soon engrossed in discussing urban legends of Hyderabad. The stories are all here he says. After so many years, “With images nourished/Under foreign skies/Far away from your own land,” he seems to relish working in India again. “The energy has moved to this side of the world” he says, thanks to how “society is laid out, how people interact or how conversations happen, and the expanded, complicated, plural, amorphous life that we lead.” Why isn’t that josh there I ask. “Because European society is based on compliance. You are compliant, which also makes you conventional. So even if you do unconventional things, you do it within a sort of grammar of conventionality.” Even in comics, “the West has become very internal. Very auto reflexive”.