The Showman and the Shaman

IF IT WERE possible, I would have sat on the steps of Mumbai’s Colaba Causeway and wept.

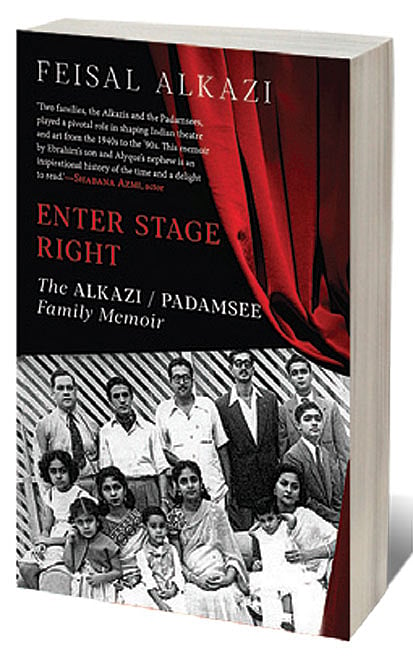

Or at least tried to during the opening chapters of Feisal Alkazi’s richly evocative era of Mumbai’s English theatre world. He documents the collective passion of the two families—the Alkazis and Padamsees—to which he belongs and the two great cities Mumbai and New Delhi that formed the backdrop to their theatrical journeys.

There is a whiff of Midnight’s Children in the tumult of his maternal grandmother Kulsumbai’s home at Kulsum Terrace on Colaba Causeway. An affluent family of Khoja Muslims from Gujarat, the Padamsees were at the intersection of conflicting cultures. Kulsumbai made sure that her ever-increasing brood received the best of an Anglicised education even as she held them together with her gargantuan Sunday lunches.

Many decades later it was here that I watched a production of Alyque Padamsee’s staging of Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party. Two rows of seats were positioned at the far end of the room. The actors were up close and neurotically engaged with Pinter’s entanglements. It was difficult not to feel suffocated. Theatre was not entertainment. It was visceral. It had to grab you by the throat and grind you into the depths where you might glimpse alternate visions of who you might be, or even could be.

“Are you God, as many people suggest?” I asked Alyque Padamsee during an interview for Debonair. He was at the height of his career as an advertising maverick as well as the most imperative of theatre directors of the time producing musicals like Jesus Christ Superstar and Girish Karnad’s Tughlaq, a play fraught with allusions to the dangers of an authoritarian state. He fixed me with a Jinnah level glare, clamped his mouth and did not answer. Gods don’t need to.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

There are many deities that parade through the pages of Alkazi’s memoir. The two that stand out are Alyque Padamsee and his brother-in-law, Ebrahim Alkazi. Feisal Alkazi introduces his father’s family as Baghdadi Arabs who had settled down in Pune. Ebrahim is just 18 when he meets the most charismatic of the Padamsees, Sultan—or Bobby as he was known at St Xavier’s College in Mumbai—during an amateur production of Oscar Wilde’s Salome. When the young Parsi actress refuses to perform the erotic Dance of the Seven Veils, Bobby gets his sister Roshen to take her place. Feisal adds: ‘That’s how my parents met.’

The second part of the saga takes place in Delhi where Ebrahim Alkazi becomes the mediating force at the National School of Drama in Delhi.

The focus also changes to plays in Hindi and those translated from the regional. If Alyque was the consummate showman, Alkazi senior was a shaman. He transformed the scripts and the young actors by a rigour that combined the different acting methods as also the need to create a language for a society still struggling from a fractured past. Whether in the intimate environs of the Triveni Kala Sangam auditorium, or the Art Heritage gallery run by Roshen, the space for discussion and dissent was always open.

Feisal’s text flits between revelations of old family secrets, short resumes of both the dramas and divas who glittered onstage and his own trajectory as actor and director. He also pays a tribute to Safdar Hashmi. Earlier on in Mumbai, Pearl Padamsee had directed The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, an indictment of how we the people create our leaders. Then again, Feisal reproduces a haiku by his mother abandoned by her husband. The solitary bird/Sings. Feisal has a whole aviary behind him. Every page sings.