The Right to Love

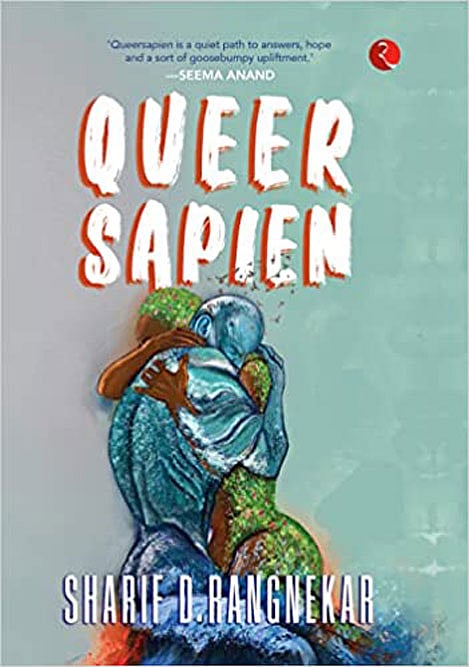

“To be queer is to prefer democracy and to uphold its tenets,” writes Sharif D Rangnekar in the preface to Queersapien. This might come across as an unusual definition to readers who associate queerness mainly with deviance from heterosexuality and assigned gender identities. It is, nevertheless, a compelling one since the validation that millions of queer people are seeking—in India and the rest of the world—is couched in the language of rights and justice.

Rangnekar identifies as a gay man. He uses the word “queersapien” to imagine an evolutionary state where queerness goes beyond roles, labels and gatekeeping. He envisions self-realisation rather than victimhood, camaraderie rather than confrontation, as the basis of queerness. He articulates this in a manner that is poetic and sensual, which makes it sound like less of a manifesto and more of a prayer and a dream.

Unlike Rangnekar’s last book Straight to Normal, where he focuses on telling his own story, Queersapien places him in the wider context of the queer community in India. This allows him to talk about hate crimes, lack of access to healthcare, discrimination in educational institutions, and abuse in homes—all of which continue even after the Supreme Court read down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code in 2018. He also writes about queer people who seek freedom by leaving India and settle down in Europe, Canada and the US.

At the same time, Rangnekar acknowledges the walls that queer people—gay men in particular—build to exclude each other on the basis of “body type”. What is often stated as an individual preference is informed by identity markers like class, race, caste, as well as prejudice towards gay men who are comfortable with their femininity and feel no need to pass off as straight.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In Queersapien, Rangnekar writes about being born to a Brahmin father and a Kshatriya mother. Apart from this declaration of caste privilege, he also admits to being drawn to slim and youthful “Oriental-looking” waif-like boys with little or no hair on their face or the rest of their body. To pre-empt critique, Rangnekar quickly supplies the information that a psychologist once reassured him that being “lured…towards the younger lot” was not “merely a queer thing”, and that “even heterosexual men were attracted to far younger men, and many women liked much older men”.

Besides sharing these innermost feelings without the filters of political correctness, Rangnekar takes readers on a literal journey. He weaves together a colourful narration of his adventures in Thailand where he got to explore his sexuality in a way that he was unable to in India. Before he could let himself pay for sexual services, he had to silence the judgemental voices in his own head. What made matters worse was the ubiquitous sight of heterosexual honeymooners from India making comments within earshot.

The common thread across all the sexual experiences that Rangnekar recounts is a search for love. He writes with great tenderness and vulnerability about what it means for a gay man to keep looking for the one. While he does not say much about the man identified in the dedication and the acknowledgements as “the love of my life,” he does get nostalgic about former lovers.

The love story that is presented most vividly revolves around a man he first met at a hotel room in Bangkok. It was the end of a long day, and Rangnekar decided to book a professional massage therapist to soothe his nerves. This massage was followed by an intimate sexual encounter, and Rangnekar urged the man to stay overnight. They learnt about each other’s lives, kept in touch, and the author invited him to spend a few days at his home in Delhi. Read the book to find out what transpired when the client and the service provider became equal partners.