The Quiet Patriotism of Ravi Varma

IN 1906, WHEN Ravi Varma was back at his ancestral home, working on a final commission from Mysore, his diabetes took a turn for the worse. A carbuncle appeared on his body but the surgical operation that followed led to complications: at two o’clock on 2 October, the artist passed away. He was already by then no longer up to the mark emotionally. As his obituary in The Hindu reported, ‘By his brother’s untimely death [in 1905], Mr Ravi Varma sustained a heavy and irreparable loss’, from which he ‘never wholly recovered’. So too in a letter written in the same phase, Ravi Varma revealed his vulnerability when he termed himself a paapi (sinner). Besides, as with most human beings, life had brought its disappointments: if he saved his father’s family from financial ruin, he also failed to prevent his older son from going astray. He had succeeded as feudal head of the Kilimanoor clan, but there were private debts to pay. His granddaughters were princesses, but his marriage had been a turbulent affair. Indeed, another regret was also that though he had painted the who’s who of the day, he had not thought to do a portrait of his own mother before her death. And now, just short of sixty, the artist’s story came to a sudden end. He might have been consoled to know that his passing was widely lamented: as a former governor of Madras wrote, ‘When I think I would not see Ravi Varma in this world anymore, my heart is filled with sorrow.’

Ironically, however, soon after his demise, Ravi Varma’s legacy was challenged—the man held to be ‘unrivalled among Indian Artists’ was by 1911 coolly dismissed as ‘a once famous native artist’. The reasons were largely political. This was a time when nationalism was acquiring a more forthright tone; in the age of swadeshi, anything foreign was suspicious. Ravi Varma may have painted Hindu gods and scenes, but his use of a Western style meant he was no longer worthy of esteem. He was accused of participating in an ‘orgy of foreignism’ and had apparently ‘swallowed with open mouth’ un-Indian inspirations. Aurobindo proclaimed him the ‘grand debaser of Indian taste’. Sister Nivedita decried Ravi Varma’s Shakuntala, who, to her, was wholly ‘ill-bred’: ‘Every home,’ she cried, ‘contains a picture of a fat young woman lying full length on the floor writing a letter on a lotus leaf. Abanindranath Tagore’s Bharat Mata ‘in her homespun sari’ as a ‘virgin mother rather than a temptress’, she argued, conveyed a more respectable ideal. The critic, Ananda Coomaraswamy, meanwhile, decided that Ravi Varma was not just ‘vulgar’ but ‘ten thousand times more so than Raphael’. His art was ‘not national art’ and while he had had an opportunity to inspire a pan- Indian aesthetic, he had regrettably missed the bus.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

Viewed in isolation, the artist’s fall appears dramatic. But the fact is that it was a generational affair. As we saw earlier, Madhava Rao and Seshiah Sastri too—for all their achievements and reputation— fared poorly in the eyes of their younger countrymen. At one time they were icons, but as colonialism was delegitimized, the fact that they had worked within its rules saw them consigned to the proverbial dustbin. Indeed, older Congressmen too were paid in the same coin—men who, like the native statesmen of the day, advocated moderation and saw little contradiction between nationalism and pledging allegiance to the queen. Indeed, much of the stigma comes precisely from the lack of vigour in their tone; from the fact that they played it safe by shrouding subversion in coy words of loyalism. Their world was, moreover, dominated by elites, with the larger public excluded, and the fact that these early Congressmen showed faith in princes too became jarring. By the mid-twentieth century Nehru, for example, would describe the states as ‘sinks of reaction and incompetence’ and the ‘[o]ffspring of the British power in India, suckled by imperialism’. To his peers, the compact their predecessors forged with the maharajahs was embarrassing. But as BR Nanda observes, the fury this generation faced is explained by the ‘conscious superiority and almost contempt with which each generation tends to judge its predecessor’. After all, there are those today who feel Nehru was deracinated and not in tune with India’s cultural realities.

But as always, viewed in context, much of what Ravi Varma’s generation did—and in the way they did it—makes sense. Perhaps this can be put in perspective by studying the Congress itself. For instance, the early nationalists’ conciliatory language towards the Raj is easily explained. Many Congress founders were born before 1857. Wounds from the Great Rebellion were too fresh for revolt to hold appeal. So also mass awakening, premised on the existence of an overarching Indian identity, in their day was at a discount. People still thought of themselves as Banias and Brahmins, Marathas and Mewaris, and through prisms emphasizing difference, not oneness. A peasant in Gorakhpur had little contact with or knowledge of peasant life in Malabar, let alone the capacity to march together for change. Nationalism was not a given—it had to be slowly constructed. And this was no easy task, even at elite levels. Why, there wasn’t even a common mother tongue in which to formulate a political vocabulary: the circular inviting delegates to the first Congress aspired to a ‘Native Parliament’ and yet required them to be ‘well acquainted with the English language’. For otherwise there could be no exchange. Even the Congress’s nationalism, that is, was for a long time a work in progress—and while its success was limited, its leaders were originators of an important historical process. They may have played by rules set by foreigners, but passive they were not, finding their own creative responses.

The task of the first generation of Indian nationalists was made doubly tough given how critics accentuated every contradiction. When the first seventy-two Congress attendees met in 1885, one paper—studying the bewildering array of complexions and costumes gathered—sniggered that this effort at national integration resembled an evening of fancy dress. The very thesis that Indians, divided by caste, religion, food and even bathing styles, constituted a nation was a newfangled position. So uphill was the nationalist task, in fact, that as late as 1903 an ‘Indian’ cricket team failed to materialize because nobody could agree as to how many social groups in what proportion might claim that label. Besides, enough Indians were anti-Congress. One north Indian critic, for example, declared it as ruled by eastern Indians, and refused to ‘lick the Bengali shoes’. The Times of India lampooned the party as a ‘suburban literary society at whose meetings a number of earnest people read elaborate essays’. Nationalists were told they were not representative of India: real India lay with the poor. The poor did not ask for democracy—why should men in coats seek it? The United Indian Patriotic Association claimed the Congress wanted ‘misrule and anarchy’. Amusingly, the nationalists were derided for their moderation even then: ‘Those who wish to dictate how India shall be governed, ought to talk at the head of an army.’ If they could not marshal troops, they had better keep spines flexible.

IN OTHER WORDS, even creating a limited anglicized nationalism was a formidable task. There was no pre-existing national energy that could be harnessed: it had to be carved out, developed and nourished through an elite consensus. This too was why early Congressmen empathized with the princes and borrowed their technique of couching anti-colonial feelings in flowery language. They could not afford to be shut down: singing ‘God Save the Queen’ screened them from charges of disloyalty while granting access to political principles borrowed from British democracy. Indeed, at the first Congress, delegates went out of their way to proclaim loyalty: ‘Had it not been for English education and Western civilisation,’ one declared, ‘persons inhabiting different parts of this vast country . . . could not have this day met together.’ A fellow participant agreed that a ‘desire to be governed according to the ideas of Government prevalent in Europe was in no way incompatible’ with ‘thorough loyalty’ to the Raj. All they wished was that ‘the people’ should have their ‘legitimate share’ of power. While this choice of tone made later Congressmen recoil, contemporary critics saw through what the nationalists were doing. As one remarked, ‘the speeches of the agitators abound in loyal protestations’ and ‘cheers for the Queen-Empress’. ‘But the whole thing is obviously forced and artificial.’ Which then raises the question: if we can sympathize with the moderation of the early Congress, might we also extend that courtesy to contemporary princes and their ministers?

Solidarity, in fact, came easily to brown royalty and early progressives under colonial authority, for both had incentives in smashing imperial claims about native incapacity for government: the princes to deter interference and educated Indians to win power. For all its supposed sins—the glorifying of princes who would eventually get on the wrong side of the nationalist cause, and the dominance of an anglicized class—at that time when options were fewer, and nationalism was an elite coalition, these figures made a profound difference. To diminish that phase omits how, if nothing else, they built the intellectual foundations upon which taller efforts could be imagined. It is, in other words, easy to criticize the output by subsequent preoccupations. Only when viewed in context can each be understood in the right perspective. That Congressmen like Gokhale and Ranade served the colonial state in official capacities does not diminish their patriotism. So too that the maharajah of Mysore did not join street agitation, but inspired Indians by showcasing bold industrial experiments is a valid part of anti-colonial resistance. Madhava Rao may have been cautious about upsetting the British regime, but he demonstrated admirably that a capacity for governing well had nothing to do with the colour of one’s skin. Against what, for example, a Gandhi achieved later, these may seem like small victories. But it was, arguably, the coming together of several such small streams that later allowed nationalism to grow into a great and powerful force, capable of breaking the empire.

There was also another reason why both the early Congressmen and those in princely territory worked within the Raj’s conceptual frame. While colonial injustice was real, it had critics even on the British side. In 1853 an India Reform Society was founded in London, criticizing Company rule. John Bruce Norton’s analysis of the Great Rebellion of 1857 excoriated his countrymen: ‘We have governed too much for ourselves, too little for the people,’ he argued, simply ‘to extract revenue’. Lord Ripon, the liberal viceroy, advocated Indian participation in administration, believing this essential for the moral and political justification of the empire. Many of his efforts, were thwarted, but Indian regard showed itself in the thousands of people who lined the roads to bid him farewell. Even in the year of the Congress’s founding, the journalist William Digby published his India for Indians in which he called on the British public to demand better treatment for the queen’s Eastern subjects. Given all this—the existence of British voices in favour, the toughness of even constructing a common ground among native elites—Indian politicians and thinkers of the age were quite willing to give the politics of negotiation a chance. Besides, by engaging with the Raj, they were also able to expose the Raj; by mastering its terms, they were able to highlight British hypocrisy too.

Of course, it was only natural that moderate methods would lose their utility with time; that political maturity would require new strategies. The early nationalists, like the native statesmen who served princes, hoped the Raj would live up to its declared ideals. Instead, they received insincerity and betrayal. It was no wonder, then, that the mood began to shift. By the dawn of the twentieth century the queen died and was replaced by Edward VII; British promises were proved largely noise; and Curzon, even as he feuded with princes, held an open ambition to ‘assist’ Congress to its ‘demise’. An angrier band of nationalists appeared, led by BG Tilak’s cry of ‘Militancy—not mendicancy’. There was no disagreement on goals: it was the means that provoked differences. For years ‘we have been shouting ourselves hoarse’, Tilak argued, ‘but our shouting has no more affected the Government than the sound of a gnat’. While more energetic, this approach did not lead to transformation: Indian society’s divisive nature, for example, meant a Tilak had little appeal outside his core Marathi zone. If the moderates had been too rational in their patriotic scheme, the extremist dependence on emotion in a culturally diverse country also had limits. It was only the rise of Gandhi that bridged the gap. By now, however, the princes were becoming enemies, and the moderates a minority.

INTERESTINGLY, RAVI VARMA’S death in 1906 coincided with this change in nationalist winds—the next year the Congress split between moderates and the so-called extremists. The artist himself had cultivated contacts with both sides. In the 1890s, thus, Ravi Varma requested Gokhale to use his influence within the system for pushing legislative business dear to creative professionals like him, while helping burnish his rival Tilak’s image by printing popular lithograph portraits of the man. Tilak was impressed by Ravi Varma’s portrayal of the Maratha hero Chhatrapati Shivaji, in whose name he launched an annual festival for mass galvanization. Through his affordable prints, as is well acknowledged now, Ravi Varma created a visual imagery for India’s masses across divides of region and language. He even ‘presented his goddesses . . . to convey their pan-national identity’. In an age when costume was linked to caste, he depicted Lakshmi, for example, in a ‘sari [that] did not belong to any particular region’. Instead, it was in a style that surmounted provincial limitations. ‘At a time that India was seeking its national identity,’ writes Rupika Chawla, ‘this was a very powerful message replete with patriotic significance.’ So too in his Galaxy of Musicians (1889), by featuring women from across the subcontinent, Ravi Varma conveyed that though all different, they yet belonged on a single canvas. Funded by maharajahs, admired by moderates while also welcoming the extremist vision, in his domain Ravi Varma manifested a quiet patriotism of his own.

The odium the man later attracted—for being seduced by a foreign style at the expense of the native and ‘authentic’—is also unkind. Nationalist fervour explains this, but objectively, what Ravi Varma attempted was quite natural. After all, art in India has been nourished by myriad influences, responding constantly to external stimulation. One of the great examples of Deccan art, for instance, features the Hindu goddess Sarasvati in a Persianate style. Done by Farukh Husain in the seventeenth century, it features the Hindu iconography associated conventionally with the goddess: a peacock, a veena, a lotus and a conch. And yet it reinvents her, projecting Sarasvati not in any consciously ‘authentic’ Hindu style, but in an Islamicate setting, marrying two traditions. So too in the Vijayanagara empire, sculpture, mural paintings and architectural styles welcomed innovation from across the land, and even overseas from Persia. The painters of Tanjore in the early-nineteenth century were inspired not only by indigenous schools but also by European practices. Viewed by these precedents, then, Ravi Varma’s love of oil painting, realism and its application to indigenous subjects sat in harmony with ‘tradition’. In drawing from European masters to recreate Puranic scenes, in combining his exposure to Kathakali with a Western technique and in using the camera to plot poses and frames, Ravi Varma was not renouncing Indian art but opening a new path.

Like their favourite artist, however, his patrons—the princes—too were unfairly dismissed. If at all discussed, they are usually treated in a negative light or reduced to cliché. Indeed, a 2021 book repeats the trope that India’s maharajahs were ‘resistant to political and cultural change, except in its more gimcrack and superficial forms, such as French jewellery or Rolls Royce cars’. Without denying that there were indeed princes who had a disproportionate taste for luxury, generalizations like this do not serve the study of history. Sayaji Rao II of Baroda owned limousines, but to brand him anti-change is a falsehood. Ayilyam Tirunal in Travancore was nervous about cultural transformation, but himself proved its catalyst through administrative and political reforms. Men like Rao and Sastri did not toil in multiple states to keep them ‘traditional’ in some stereotypical sense: they were hired precisely to help those principalities negotiate change, despite Raj-imposed political limitations. Even in Mewar, where Fateh Singh despised Western modes of government, he used colonial dynamics to try and amend the state’s internal structure by diminishing his vassals; ‘traditional’ Mewar too was no unchanging place. Besides, the idea that loving jewellery and cars was solely an Indian princely preoccupation is disingenuous: Western history has its share of luxury-loving spendthrift rulers, and its dynasties too have their share of scandal and intrigue.

One hopes, then, we can look at India’s princes a little more seriously. They were not unchanging relics of some ancient past, out of place in modern India’s evolution: they were part of the process themselves, even if, ultimately, they lost out. Their states were not old-fashioned islands where time stood still and society decayed: they had their own politics and internal dynamics, which are also part of this country’s tale.

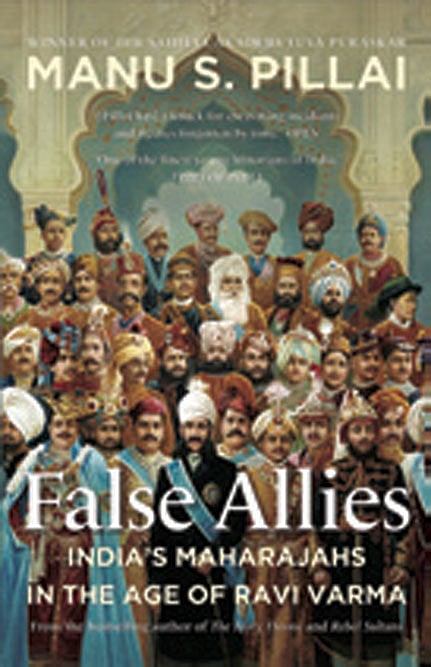

(This is an edited excerpt from False Allies: India’s Maharajahs in the Age of Ravi Varma by Manu Pillai )