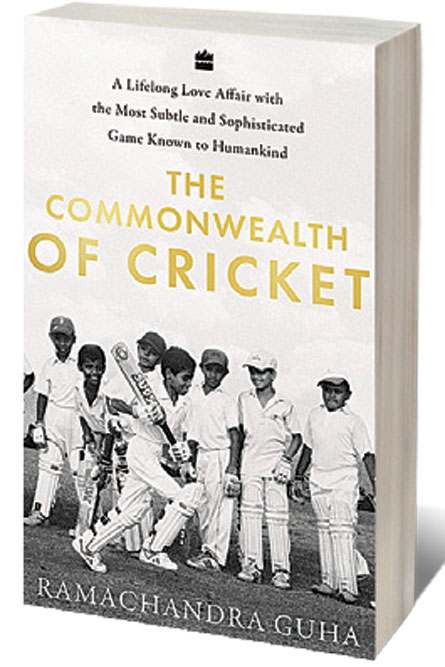

THE SUBTITLE TO Ramachandra Guha’s new book, The Commonwealth of Cricket, describes cricket as ‘the most subtle and sophisticated game known to humankind’. Some might see talk of this sort as grandiloquent. But do we need any more evidence for the assessment than that which was on offer at the recently concluded fourth test match between Australia and India? As it happened, I finished reading Guha’s book hours after the match at the Gabba ground in Brisbane coiled its way to its climax, all the while thinking to myself, as so many other aficionados around the world surely were, “Test Cricket, eh? Bloody hell.” This, though, is the catch in the book’s title: the term ‘cricket’ no longer refers to only the longest forms of the game; it hasn’t for some time now, and Guha is only too aware of this, partial as he is to the five-day game.

Test cricket, he writes, can be compared to the finest Scotch, fifty-overs a side to Indian Made Foreign Liquor, and 20-20 to the local hooch: ‘The pleasures of the shortest game are intense but also wholly ephemeral.’

Appraisals of this kind, even if not uncommon, can quickly turn classist. Some recent cricket memoirs have fallen into this trap. Notable amongst them is That Will Be England Gone: The last summer of cricket, published in April 2020, in which the British journalist Michael Henderson declares that he is no ordinary cricket ‘fan’—for fan denotes fanaticism—but a cricket lover. So great a lover it seems that the statistical claims to greatness made by the Australian batsman Steven Smith are diminished in the author’s eyes, because Smith can ‘never be mistaken for Mr. Wonderful.’ We’re asked to believe that this is the judgment of an aesthete, but it only makes it difficult to take Henderson’s lamentations about the game seriously. If you cannot take pleasure in watching one of modern-day cricket’s most accomplished players perhaps this sport isn’t one for you.

Guha, unlike Henderson, writes foremost as a fan of the sport, of a sport that gripped him in his teenage years, with the obsession surviving well into adulthood. This makes The Commonwealth of Cricket a deeply attractive read. Guha’s point of entry into cricket allows us to reckon with his grievances about the state of the sport today while marrying them with the delights that the game still offers.

The book’s most engaging portions are found in Guha’s writings about his earliest heroes. These paint a vivid picture of the players themselves, but, even more acutely, tell us how much the game has changed. Consider a short passage describing how the author came to shake the hands of a test cricketer for the first time, when he was on a summer holiday at Bangalore in 1970: ‘One morning, my uncle and I were driving in his Fiat along Nrupathunga Road when he spied a tiny figure hunched over a scooter. Durai overtook him from the left, shouted out ‘Vishy! Vishy!’, and with his shrunken right hand motioned for the man to pull up. He did, we got out of our car, and my uncle introduced me to G.R. Viswanath, who in the previous winter had scored a dazzling 100 on debut against Australia in Kanpur. That incident says something about the times— which Test cricketer now would drive a scooter?’

The uncle, N Duraiswamy, is, in many ways, at the centre of the book. It was he who garnished Guha’s nascent preoccupations with the sport. Durai, despite having only one good arm, turned into a skilled cricketer. But he believed he could realise his own dreams through his nephew, chiselling him into a test player. For all of Durai’s efforts though, Guha could do no better than play for his school and college teams—these were no ordinary achievements, but as Guha realised, when he played alongside those who represented teams at first class and test level, his talent for the sport was ultimately limited. But his passion remained undimmed.

The book’s most engaging portions are Ramachandra Guha’s writings about his earliest heroes. These paint a vivid picture of the players and tell us how much the game has changed

Share this on

This book takes us from Guha’s earliest years playing the sport through to his brief stint as an administrator. But there are plenty of ruminations about players of yore, of those who preceded his initiation into cricket. These are presented as nuggets of conversations that he had with a friend 30 years his senior, TG Vaidyanathan. TGV was an academician and a renowned film critic. Satyajit Ray, Guha writes, once described him as the ‘only Indian writer on the subject he had time for’. But TGV was also intensely invested in cricket. His conversations with Guha often revolved around his idols, Indian greats, Lala Amarnath, Vinoo Mankad, Mushtaq Ali and Vijay Hazare, but also foreign cricketers he had seen on our soil. These anecdotes took me back to discussions with my own grandfather who had taken me along to my first cricket matches, including, as a four-year-old to watch schoolboys’ cricket at the ground abutting the Marina beach in Madras. While TGV fancied Clyde Walcott’s straight drives, for my grandfather it was Everton Weekes’ spanking cover drives, a stroke that he played with such aplomb that the red ball when struck hit the ground in an instant only to scorch its way all along the grass to the boundary rope. So much of sport’s appeal lies in nostalgia, not just for a time that we ourselves were a part of, but for a time before our own, and Guha’s reminiscences with TGV, filled with myths and stories about the game, present to us the game at its most charming.

This charm gives way to disillusionment as the book wades into Guha’s time as an ‘accidental administrator’ of the game. Appointed by the Supreme Court of India to be a part of an interim committee of administrators to see the BCCI through a period of transition, he finds himself constantly thwarted, by both other members of the committee and those firmly entrenched in the sport’s management. The court’s objective was to instil in the board a set of wide-ranging reforms but undoing the cronyism required more than just good intentions. Guha reminded his colleagues on the board about the dangers of conflicts of interest—players, coaches, selectors, and commentators all took dual roles that undermined their abilities to act with independence and rectitude. But his remonstrations were either met with deaf ears or with wanton defiance, prompting him to eventually resign. Since then, the board has gone back to its old ways.

In these passages, Guha tells us much about what he thought needed changing in the administration of cricket—among other things, a need to place greater focus on the domestic game, and a need to clean up the board’s role in the telecast of the sport. Yet, if there can be one quibble about the book, it’s this: if we must see sport as a public good, as the book’s title suggests, then we need more than just a simple reformation of the BCCI. We’ll need an overhauling of how cricket—indeed how any sport—is organised in India. To that end, a reader might legitimately expect from Guha a manifesto of sorts, that tells us not merely what’s wrong with the BCCI’s rapacious ambitions but one that also speaks to the values of sport, and the specifics of how one might go about preserving those values.

Persons in favour of the status quo might point to India’s recent successes, they might even point to the commercial feats of the Indian Premier League and the wealth of the board. But, as The Commonwealth of Cricket shows us, there is more to cricket than filling up the coffers of a controlling authority; there is more to it than winning at the highest level. Ultimately, we must see cricket, as CLR James did, in Beyond a Boundary, as a common good, as an institution that belongs to the community at large.

About The Author

Suhrith Parthasarathy is an advocate practising at the Madras High Court

/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Thepitchoflife1.jpg)

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba