The Physicist Genius

HOW MANY OF us have heard of Narinder Singh Kapany, considered the “father of fibre optics” who paved the way for information technology? When Shanghai-born Charles Kuen Kao was chosen for the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work in optics, many in the scientific world expected this Indian expatriate scientist to share the coveted prize. It is still a mystery why the Nobel committee ignored him. After Charles Kao fabricated highly transparent fibres in the 1960s, Kapany continued to be in the field long after his mentor Harold Hopkins left the scene. He continued to make technological innovations such as fibre couplers and amplifiers that transformed optical fibre technology. The historic inventions facilitated transmitting unfathomable loads of text, images and video data across the globe in an instant, impacting every aspect of our lives, including the pathbreaking advances it made in the medical field, such as laser surgeries and endoscopy. Kapany is indeed a proverbial unsung hero.

Born in Moga, Punjab, to a wealthy Sikh family, after schooling in Dehradun in the 1940s, he entered the physics department at the University of Agra while also doing an apprenticeship in a factory for the design and manufacture of optical instruments. His next stop was London in 1952 for a doctorate at the Imperial College with British physicist Hopkins. Kapany, with his genius for designing experiments ,and Hopkins, with a formidable theoretical background, were an ideal combination. Within two years of laboratory work, the duo would publish their historic breakthrough in the journal Nature, where they explained how they could send a beam of light through a set of 75-cm-long glass wires. Abraham van Heel, a Dutch scientist, was also working on this problem and trying to produce coherent bundles by cladding each fibre to reduce the light leakage. He also published his findings on the same issue. These papers marked the birth of fibre optics and the now ubiquitous communication technology.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

A chance meeting with an American professor while presenting a paper changed Kapany’s trajectory. Thus, Kapany, with his partner Satinder, an Indian native studying dance in London, decided to board a ship sailing to New York and eventually joined the faculty at the University of Rochester. The American sojourn triggered the dormant entrepreneur in him, leading him to launch several successful startups in optic technology in Palo Alto in the Silicon Valley. With over 100 patents, an equal number of scientific papers and four books on opto-electronics, Kapany was also much sought after in the academic field and served as a visiting scholar at Stanford University and the University of California.

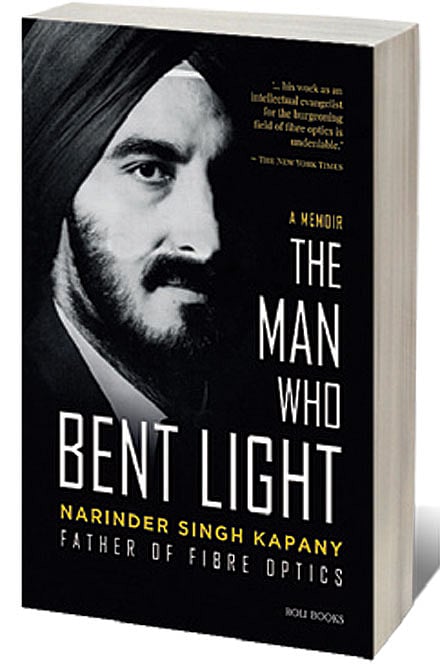

Completed almost a year before his death on December 4th, 2020, his memoir titled The Man Who Bent Light provides a firsthand account of his life and the choices he made to become a scientist, teacher, entrepreneur and a connoisseur of art while also being a loving son, husband and father. He explains how he had an epiphany while attending an introductory class in physics that impacted the rest of his life. The professor’s words that “light can only travel in a straight line” roused him from a gentle slumber. His first impulse was to shout that the teacher was wrong: light couldn’t only be travelling in a straight line. This moment was to remain with him as a constant reminder that his “life’s work [was] not only to prove that light could travel every which way but also to put this simple physical truth to work in amazing ways”. The realisation forced him to find opportunities to work and study in Britain.

Before he departed India, Kapany had to witness Partition—a searing indictment of India’s humanitarian values. He recounts how he saved a Muslim family by pointing a rifle at the crowd that came knocking on his door. This love for his fellow beings also forms the background of his lifelong Sikh religiosity—a religion whose physically manifest tenets, he thinks, are equality and charity. Kapany, who was fiercely proud of his Sikh heritage, had one of the world’s largest private collections of Sikh art that was donated to museums.

Kapany’s memoir stays clear of the controversies, including his take on the decision of the Nobel committee that sidelined him. The book reads much like a sanitised version of his memories, devoid of harsh judgements of people or events. For instance, the relationship with his mentor, Hopkins, at the Imperial College was said to be not smooth. Hopkins wanted the primary credit of the research for himself, but Kapany thought that it was he who translated the theory into a practical reality. In an obituary of Kapany, Clay Risen writes in The New York Times (January 7th) how Kapany had fought with Thomas J Perkins, a co-founder of a company they established in the Silicon Valley, over the company’s vision. Perkins said it was “a mutual hate for each other of near biblical proportions.” And later added that he wanted to engrave on his tombstone “I still hate him”. It is reported that Perkins eventually demanded the board choose between them; and they chose Kapany.

The memoir is silent on such incidents in Kapany’s life, though his style of writing is breezy and often tongue-in-cheek. One such instance in his memoir is his amusing meeting with VK Krishna Menon, the then defence minister of India, known to be capricious in his interaction with people. Menon was favourably impressed with Kapany and wanted him to return to India as an advisor to the defence ministry. Kapany gives a humorous account of the meeting with Menon in the latter’s hotel room. Menon emerged from the bathroom dressed in boxer shorts and a shirt to say hello and without any initial niceties, Kapany was asked to thread a long drawstring of a pajama. In an innovative move, Kapany appropriated a large paper clip from Menon’s desk to thread it through the waistband. At the end of this session, Kapany accepted Menon’s invitation and finally reached Delhi to meet Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who was also equally well-disposed towards him. The offer letter from the lethargic Indian bureaucracy, however, took almost a year to reach him. By then, Kapany had chosen to set up his startup, one of the first venture capital-based companies in the Silicon Valley, the Mecca of tech entrepreneurs, rather than returning to India. Despite his love for research, his memoir gives ample evidence that his dominant interest is doing business. He used to tell American listeners that he was there to “do an Indian optical trick”.

Kapany’s memoir gives us an account of the life of an Indian immigrant in post-war America who led an extremely successful professional life. His son is reported to have said: “He used that turban like a lethal weapon. When you see a guy, who looked like that and who spoke like JFK, you’re not going to forget him.” Kapany’s life was of epic proportions and what finally stands out much above everything else is his love for his wife Satinder—to whom he owes so much of his success. The book eminently evokes times, experiences and places that defined his life. He ends his story with his concerns about climate change, environmental degradation and social unrest that may hurt our future and underlines the need to foster love and compassion—the values dearest to his heart.