The Phantom Invasion

THE GREAT FLAP OF 1942 is an unusual study of India’s World War II history, the way the British Raj dealt with Japan’s invasion of Southeast Asia, immediately following its attack on Pearl Harbor on December 6, 1941. The book’s focus is on the events of 1942, when Japan seized in rapid succession Malaya, Singapore, and Burma. British India, along its entire eastern seaboard, waited for Japan’s attack.

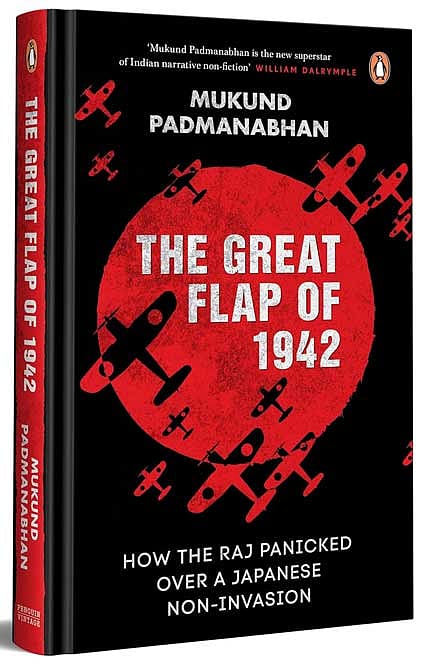

At least in part the book belongs to the category of subaltern history, depending on the personal memories and accounts of actors of that time. At the same time, a fair amount of the material comes from archival research at the grassroots level. The book’s subtitle: ‘How the Raj panicked over a

Japanese non-invasion’, neatly sums up the story. It is short (just 200 pages of main text), written with gusto, and is a delightful read. As author Mukund Padmanabhan’s debut, after more than three decades as a journalist and an editor, it sings with freshness.

A short introduction sums up the way widespread panic surged across east and southern India, following Japan’s three-month march, virtually unopposed into Southeast Asia “ripping apart like muslin the Empire that was woven purposefully over the centuries”. That generated fear, panic in Calcutta, and along the entire eastern coast, up to Madras and beyond. Driven by a mindless fear of a Japanese invasion, over 20 per cent of Calcutta was emptied of its population, in a matter of weeks. The irony was that Japan had no plans to invade India, notwithstanding several air raids by Japanese aircraft that sank ships, virtually unopposed. Japan’s aircraft-carrier forces also made some forays in the Bay of Bengal in that early phase, causing a carnage among British naval ships. They also occupied unopposed the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, besides doing serious damage in Ceylon with their bombardment.

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

Some of the narrative is based on newspaper accounts of the time, from major publications like The Hindu (Padmanabhan retired as its Editor in 2019) and The Statesman, and from other papers, as well as the records of the provincial Assemblies, and local papers from the municipal authorities. Fear-driven edicts issued to the local population by the provincial and local administrations are cited, as also the hasty evacuation of offices from cities and towns, into the rural interior. As a former journalist, the author graphically sketches the panic.

Padmanabhan cites Indivar Kamtekar to suggest that our historians have been obsessed with the Independence story as played out in New Delhi, and the related manoeuvring among Congress and the All-India Muslim League, manipulated by Viceroy Linlithgow and his colonial administrators. In the process they have neglected the “shiver of 1942 into the margins”. That’s an interesting point, because that same obsession with the New Delhi drama, dominating contemporary newspaper reports, has precluded our historians from examining archival documents that framed the key aims of British government policy towards India. Rather too little attention has been paid, for instance, to the role played by US President Franklin D Roosevelt, and his strong pressure on Winston Churchill to prepare India and other colonies for self-governance at the end of World War II. Of course, Churchill deeply resented this and pushed back, as visible through the documents at the centre of British power, especially the rich correspondence between these two principal Allied leaders.

The author offers a remarkable factoid that because of a panic reaction by the governor of Madras, an official asked residents of the city, whose presence was not essential, to leave, and that by the middle of April between 75 and 90 per cent of the city’s population had been evacuated. This is a vivid example of thoughtless maladministration, one that is unrecorded in mainstream history accounts.

The book begins with the story of Japan, the easy occupation of Malaysia and Singapore, which lead to the foundation of an easy assault on Southeast Asia. The first three chapters narrate the big picture. The following two chapters cover in detail Japan’s naval and bombing rampage in the Bay of Bengal in those early months, and the air attacks on Ceylon and on Indian coastal shipping, before its early surge was bogged down in its land campaign. (That also ended Japan’s capacity to block the US-led ‘air bridge’ that was developed out of Imphal, to supply the Chinese forces of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Communists, in mainland China at their Chungking and Szechwan bastion, though the book does not address this.)

In Chapter Six, the narrative turns to the reaction of Indian political parties to the September 1939 outbreak of World War II, and the political confabulations in New Delhi, and in London. We see again in vivid fashion the knee-jerk reaction of Congress, in quitting the nine provincial governments where it ruled, unmindful of their own strategic interests.

The narrative then returns to a detailed account of the evacuation of Indians from Burma, following Japan’s march into Rangoon, a city of two million inhabitants of whom almost half were Indians. There are poignant accounts of the starved and disease-ravaged forced to march as refugees from Burma into India and their subsequent travails.

The chapter titled ‘The Madness in Madras’ is evocative with an abundance of detail of the manner in which as much as

55 per cent of the population—at that time eight lakh people—was evacuated under the threat (completely ill-founded of course) that Japan was about to invade Ceylon and a major southern Indian city, either Madras or Visakhapatnam. It is rich in detail, with several personal accounts, sourced from those who underwent the experience. This sheds new light on how the British Raj was reduced to total panic in 1942.

This book is striking precisely because there have been very few accounts of the subaltern history genre. The author creates a graphic ground level history of events. We do not have many examples of this kind of writing, and it speaks to Padmanabhan’s meticulous search for fresh material.

The Great Famine of 1942-44 is mentioned for the first time on Page 68, but connections between that tragedy and the perceived threat from Japan are not explored. This became a major factor in the Great Famine that took over three million lives in Assam, Bengal, Bihar and Orissa in early 1942. The Japan threat had three consequences in Bengal: ill-considered actions by the British military to destroy rural food stocks, even the family subsistence stores of farmers; a collapse of the local-level administrative system; and internal rivalries within the elected provincial government—all these hinged on the Japan threat. That coincided with a season of poor rains and blockage in traditional rice supplies from Myanmar. The threat of a Japanese attack did not cause the famine, but it contributed to its severity, and to the chaotic response by a seemingly paralysed British Indian administration. That is directly relevant to the book’s principal theme. It is hard to understand this omission.

Throughout, the book presents the perspective of how Madras and other parts of south India saw the war and the threat from Japan. And once the phase of panic in 1942 was over, subsequent and occasional air raids by Japanese aircraft were handled with equanimity. Another strength of the book is its detailed narrative of the events leading to the formation of the Indian National Army, especially the events preceding Subhas Chandra Bose’s arrival in Southeast Asia in mid-1943.

With its freshness and wry humour, the book will draw readers. The research that it incorporates provides a solid base to the narrative. One hopes The Great Flap will inspire other authors to present their down-to-earth writing. Such perspectives are valuable in understanding the human and local dimensions of great events.