The Mythic Meets the Mundane

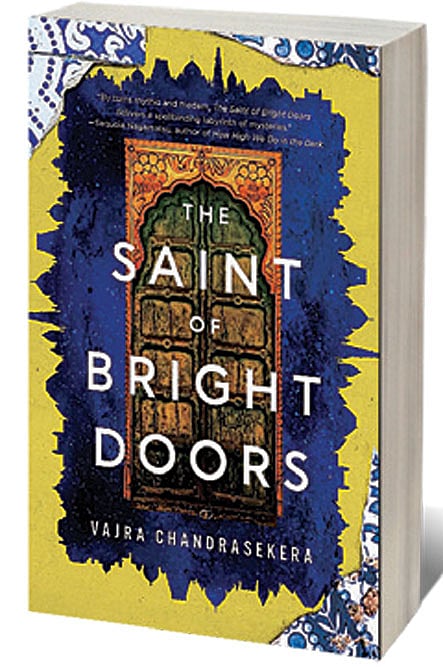

THERE’S A GREAT little passage in the third chapter of Vajra Chandrasekera’s debut novel The Saint of Bright Doors (Tordotcom; 368 pages; ₹650), about the protagonist moving to a big city for the first time. Young Fetter was born to strange and powerful parents. His father, called ‘The Perfect and Kind’, is the messianic leader of a cult named ‘The Path Above’. His mother, referred to as ‘Mother-of-Glory’, resents her estranged husband and the spell he has cast over just about everybody, it seems. She brought Fetter up as an assassin for a mission targeting his father and his cult, but now young Fetter has moved to the massive island-city of Luriat (clearly modelled after Sri Lanka) and has different priorities in life.

“The city told him he was done wandering, done with his mother’s quest. Now he is starting to feel like he belongs there. So many people come to the city from somewhere else that it’s easy to feel at home. Fetter isn’t even the only feral child of a messiah in his social network. There’s a support group for unchosen ones, which was recommended to him by the therapist he’s been seeing ever since he learned what a therapist was.”

Note the elegant personification in the first clause (“the city told him”), the little joke about therapists at the end, not to mention the casual hilarity of “isn’t even the only feral child of a messiah in his social network”. The Saint of Bright Doors is a finalist for the Hugo, Nebula and Lammy awards, announced over the last couple of weeks—these are some of the most prestigious awards in the world of fantasy and science fiction. The novel has been repeatedly hailed for its inventiveness and creativity. The New York Times’ science-fiction and fantasy columnist writes, “I can’t remember the last time a book made me so excited about its existence, its casual challenge to what a fantasy novel could be. In its slipperiness, its combination of antique registers (‘megrims’ for migraines, ‘haecceity strings’ for bar codes) with contemporary digital life, it manages to pinpoint the peculiar insanity of our modernity.”

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

During a video interview, the 44-year-old Colombo-based writer speaks about his childhood, the making of his debut novel, and the role played by allegories in speculative fiction. He wrote this novel during the first wave of the pandemic, having worked previously in IT for nearly a decade. Chandrasekera says, “I made a late arrival to writing, you can say, in my early 30s. During the pandemic, I just thought, ‘If there was ever a sign that you should buckle down and finish this thing, it’s this’. I actually ended up finishing another book right after this one.” That book, another fantasy novel called Rakesfall, will be released in June. Chandrasekera’s father, a civil servant who was born before Sri Lanka gained independence, was a novelist in his own right in the ’70s and ’80s, with “a couple of books that sold well”. But he also advised his son not to take up writing full-time, to pursue literary ambitions by night, after the regular workday was done.

Chandrasekera says of his father, “He wrote his first novel at the time my mother was pregnant with me. It was full of things that had actually happened to my father, things that people in my extended family were aware of. Today, such a novel would be called ‘autofiction’, I suppose. He was usually posted to very remote areas and there wouldn’t be much to do there. Some of my earliest reading memories are from this phase.”

In The Saint of Bright Doors, the island-megapolis known as Luriat is where Fetter moves to and its relationship with the real Sri Lanka is developed in broad strokes, for the most part. We are told that the religious and political structures in Luriat are impossibly complicated, and the language is written in over a dozen scripts, all of which are equally valid and ‘correct’. The cult led by Fetter’s father, The Path Above, isn’t even the dominant religion here: that’s ‘The Path Behind’ (when I read this bit for the first time, I had to put the book down briefly, on account of a giggle-fit).

Certain passages make the connection clear, however. Like a passage that parodies the recent political upheavals of Sri Lanka via a description of Luriat’s chief political structures. It’s darkly funny stuff that balances an almost Wodehousian tone with deadly serious indictments of the status quo. The major political parties are more concerned with the finer points of “Alabi race science” than the minutiae of governance. The city’s mayor “skips from embroilment to embroilment, one scandal to the next”. The Cabinet ministers count several former warlords and drug barons among their ranks, and the Parliament is susceptible to sudden collapse, the electorate having grown weary of their antics after one repeat performance too many. Similarly, the High Priests of the Path Behind are described as “venomous men in blood robes”.

The ‘High Priests’ referred to here resemble any number of nationalist Buddhist monks, like Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara, the leader of the Bodu Bala Sena. Only last week, a Lankan court sentenced Gnanasara to four years’ imprisonment for an anti-Muslim hate speech he delivered. “There are basically several factions of fascist Buddhist monks in Sri Lanka,” Chandrasekera says. “They align themselves with various parties in the hope that their faction will come to power. Come election year (like this one), some of these monks are arrested largely as a publicity stunt. This particular monk (Gnanasara) was arrested previously, too, years ago, but received a presidential pardon eventually.”

IT SHOULD BE noted, however, that Luriat isn’t a simplistic, match-the-column analogue specific to Sri Lanka. As the earlier passage about Fetter leaving home shows, Chandrasekera uses Luriat as a stand-in for a specific set of qualities— pluralism, cosmopolitanism, the kind of easygoing tolerance that an impossibly diverse place develops organically over time. It’s not all utopian, however. There’s a great moment about halfway into the book where Fetter tells his mom over a phone call that he’s dating another man—that too a man of much higher social standing, according to Luriat’s strict hierarchy. Mother-of-Glory takes it in her stride, expressing no personal disapproval of Fetter’s choice. However, in the same sentence she warns him to keep the relationship a secret, lest he gets into trouble with the authorities.

In fact, one of the reasons the phone call works as well as it does within the context of the novel is that Chandrasekera is suggesting, gently, that the hierarchy-bending (or exogamy) is a much bigger deal than homosexuality (technically illegal but not always vigorously prosecuted). Every citizen of Luriat carries a card on their person at all times. This centralised ID contains not just their name, age et al but also their positioning within Luriat’s quasi-caste system. Everybody, therefore, always knows who is beneath whom and by exactly how much. The Saint of Bright Doors is full of complex, ambitious ideas like this one. Like the idea of the titular doors themselves—in Luriat, any door that is left closed for too long has the potential to become a “bright door,” portals between this world and the next, gaps in the fabric of space and time through which “antigods” and devils can slip through.

And Fetter is like no other protagonist you’ll ever come across. Raised as the proverbial lethal weapon, it’s a delight to witness Fetter’s transition into the classic existential hero (sometimes gradual, abrupt on occasion), trying to figure out his capital-S Self, the world and his rightful place in it. Like all existential heroes (or antiheroes) he is searching for a sense of purpose, but he’s hardly unique in that respect. One of Chandrasekera’s best-executed writerly gambits is to play with our expectations of a ‘main character’. At every step Fetter encounters people and objects that are every bit as ‘special’ as himself, if not more.

“When you leave your hometown and come to the big city for the first time, everybody feels like a main character,” Chandrasekera says. “When Fetter meets his support group for the first time, he realises that everybody there has supernatural abilities in one way or another. Everybody is the ‘main character’, to that extent.”