The Mind of Music

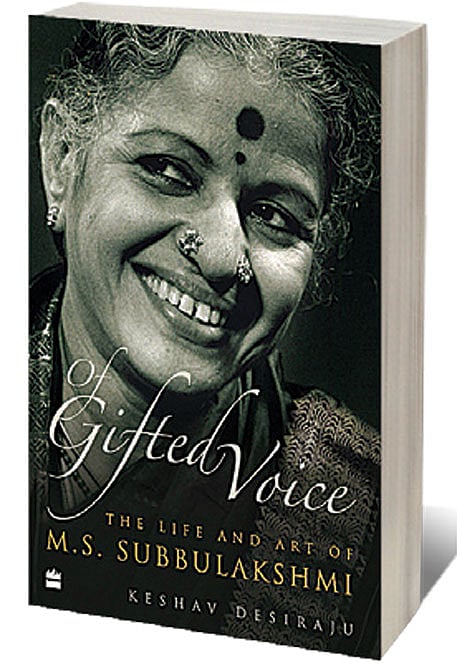

IT IS IMPOSSIBLE to author a truly innovative biography on MS Subbulakshmi, on whose life and art endless tracts have been written over the years. If you are expecting a presumptuous spin to her story, Keshav Desiraju’s new book is not it. A thorough and respectful scholar, he pours into Of Gifted Voice a mass of information and insights from previous biographies by TJS George and Gowri Ramnarayan, news articles, reviews from Sruti, Ananda Vikatan and Shankar’s Weekly, speeches by Gopalkrishna Gandhi and the music scholar V Sriram, letters, and sabha and radio logs. It is to his credit that he interweaves this wealth of material with original observations on the evolution of her music and the socio-politics of her times to present a detailed, if linear, account of a life marked by choices that continue to perplex us: her ‘escape’ from the social milieu she was born into and into the protection of T Sadasivam who would take control of her career and shape her into a national icon; her readiness to subjugate her talent and imagination to present a relatively small, highly-finished repertoire beloved by audiences; and her self-conscious transformation into a symbol of Brahminical piety. Desiraju wrestles with the same questions, often looking for clues in the lives of others who influenced Subbulakshmi. There are tangential passages on the Carnatic trinity of composers—the author’s bio suggests he may be working on a book on Tyagaraja next—and on her mentors, powerful friends and contemporaries, especially women who, like her, came to define an era of south Indian art while re-negotiating their own position in society.

The stand-out contribution of the book is its close and careful reading of Subbulakshmi’s repertoire over the years. From her early concerts, such as a memorable one at the Music Academy in 1939, Desiraju singles out moments when she was so lost in her music that she launched into a Kalyani alapana having just concluded a song in the same raga, and pieces like Muthuswamy Dikshitar’s Chintaya ma (Bhairavi) and Kavi Kunjara Bharati’s Ivanaro (Kambhoji) that would later be expunged from her ‘armoury’. Both, the author finds, were sung the previous year by GN Balasubramaniam. GNB, as he was known, was the love of her life, to go by the letters she wrote him after they starred together in Sakunthalai (1940), as revealed posthumously by TJS George in his biography.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Her husband’s stage-management of her image would become evident in the coming years. ‘That Subbulakshmi was capable of inspired improvisation was in no doubt; that she should have been made, machine-like, to repeat herself can only be regarded as unfortunate,’ Desiraju rues, referring to a clutch of similar recitals in the late 1950s—a period that saw her racing through stock songs in nearly every concert, with the exception of inspired and original performances such as one in Erode, in 1956. Slowly but surely, Subbulakshmi was becoming a creature of habit: Maithreembhajata, a composition attributed to the senior Shankaracharya of Kanchi, was first sung at the 1966 UN concert and thereafter, became her concluding item in every concert for the next 30 years, notes the author; in similar fashion, the Dakshinamurti Stotram, which she debuted at an August 1971 concert, became her preferred opening piece for the rest of her career.

In Desiraju’s copious notes, running into nearly a hundred pages, followed by appendices on the dramatis personae of her life, and suggestions on songs and where one might find them today, one can spy hidden gems on her most inventive sangatis and humorous cultural asides on the Venkatesa Suprabhatam (1960) and other chants that made her a household name. Despite the fact that she chose to be remembered for her piety, Desiraju, like other writers before him, disagrees with a popular perception of Subbulakshmi as a singer lacking in ‘vidwat’. At the risk of contradicting his book’s title, he attributes her extraordinary success as a performing artiste to her rich repertoire (of over 2,500 songs) and strength in raga alapana as much as to her fabulous voice. An analysis of her virtues as a musician—her diction, grasp of swarasthanas and laya thanks to her familiarity with the veena and the mridangam, and restraint in rendering ragas, among others—would, of course, amount to another book or two.