The Malabar Angle

IN THE POPULAR narrative of the Indian national movement, there are many dark spaces. Many valiant battles, fought both at the mass level and by individuals, have been forgotten or perhaps deliberately brushed over. In the process, a sense of the enormous diversity and complexity of the struggles for freedom waged by Indians of all regions and communities has, to a great extent, been lost.

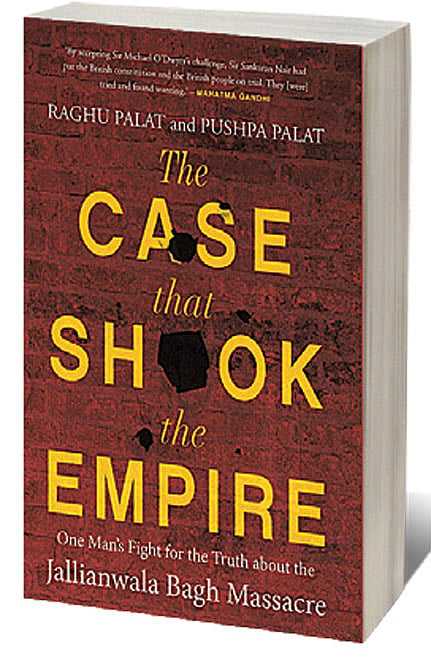

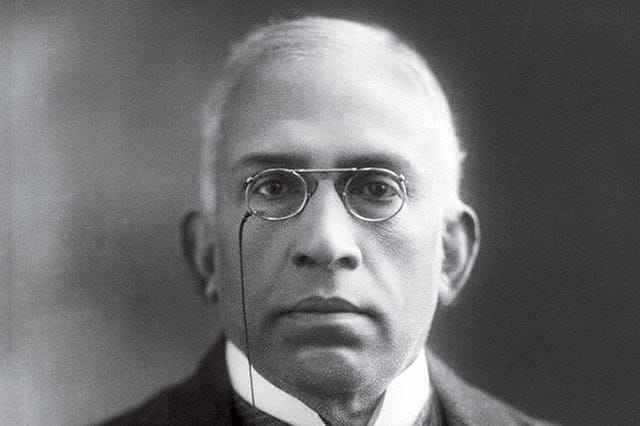

Raghu and Pushpa Palat’s book is an attempt to recover and highlight one of these largely forgotten struggles. It tells the story of one man from Malabar in Kerala, Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, who in 1924 fought a lonely and lengthy legal battle in London against Michael O’Dwyer, who as Governor of the Punjab had presided over the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. As the only Indian member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council at that time, Sankaran Nair had initially supported the imposition of martial law in Punjab as necessary to maintain ‘law and order’ at a particularly turbulent time in Punjab. However, when news of the brutal massacre at Jallianwala Bagh and of the other atrocities unleashed on the population under the infamous Rowlatt Act eventually seeped out, Nair resigned from the Executive Council in protest. The focus of this book however is his legal fight against the charge of libel levelled against him by O’Dwyer some years later, after Nair had condemned him in writing as the man responsible for the atrocities in Punjab. Nair was given the option of retracting his words and apologising but, convinced that he had said nothing that he could not defend, he chose to fight the case in England, before an all-English jury. The verdict was a foregone conclusion, with 10 out of the 11 jurors upholding O’Dwyer’s case against Nair.

Why did Nair choose to fight this case, at great personal and financial cost, when the odds were so heavily stacked against him? Was it because of his innate combativeness and towering sense of personal dignity, which could not tolerate any slight from anyone, including top British officials? The authors bring out this aspect of Nair’s character very well, recounting several delightful anecdotes. Edwin Montagu, who was Secretary of State for India at the time, had called him “an impossible man” though he warmed up to him later. Or was it because, unlike practically everyone else including his family members, he had a profound belief in the fairness of British law and the British legal system? While he advocated self-government for the Indian people, Nair was clearly a moderate in his political views in the context of the times. He believed in constitutional reform at a time when the Indian National Congress (of which he had been the President in 1897) was turning to mass agitation under the guidance of Gandhi. In fact, he disagreed so vehemently with the politics of civil disobedience that he wrote a book titled Gandhi and Anarchy (possibly one reason why he has been sidelined in the mainstream narrative of the Indian freedom movement). In spite of this, Gandhi commented in Young India after the trial that he ‘admired Sir Sankaran Nair’s pluck in fighting a forlorn cause,’ adding that ‘[b]y accepting Sir Michael O’Dwyer’s challenge Sir Sankaran Nair has put the British constitution and the British people on trial. They have been tried and found wanting.’

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Nair’s personality and career, the complex British imperial politics of the time, and a blow-by-blow account of the trial, have been presented by the authors in a refreshingly accessible manner. Their admiration for their subject is not in doubt, and they do not hide the fact that Raghu Palat is Nair’s great-grandson.

While one can ask whether the case of O’Dwyer vs Nair did in fact ‘shake the empire’, the authors must be commended for highlighting this little remembered episode in India’s struggle for freedom.