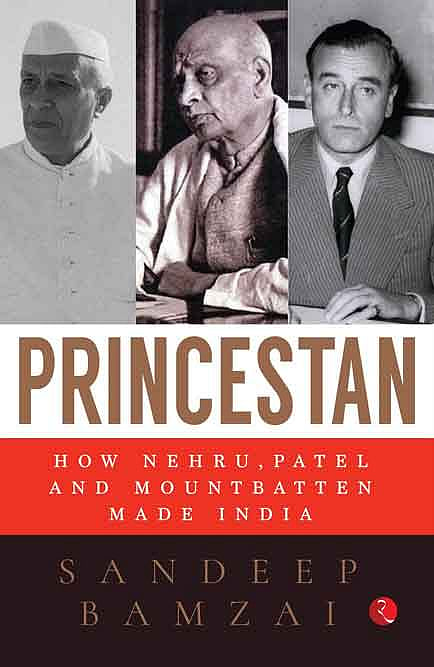

The Making of India

Ever since 2014, nefarious attempts have been made to rewrite history to deny Jawaharlal Nehru any role in the integration of the Princely States with a view to giving the credit entirely to Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (and VP Menon)—a claim never made by either Patel or his principal aide. Sandeep Bamzai has put the issue into balanced perspective in his well-researched and well-documented book, Princestan.

The expression is Winston Churchill’s. Bamzai reports that after meeting Churchill on March 29th, 1945, Archibald Wavell, then viceroy of India, recorded in his diary, that Churchill “seems to favour partition of India into Pakistan, Hindustan and Princestan”. Seeing off Wavell, Churchill said, “Keep a bit of India”. Fortunately, the British people voted Churchill out of office a few weeks later and the Clement Attlee government was elected, determined to get out of India as soon as possible as post-war bankruptcy pushed living standards in the United Kingdom to below WWII levels. But, as Narendra Sarila has shown (The Shadow of the Great Game: The Untold Story of India's Partition), what was perhaps a hint of avarice on Churchill’s part, was transformed by the defence establishment into backing Partition because they believed, not without reason, that while India would reject any continuing defence relationship with Britain, Pakistan would be more than ready to accommodate British interests. This facilitated the Political Department’s relentless efforts to convert the princes into the “Third Force” in India allied to the Crown.

To Nehru, the idea of “Princestan” was “anathema”. Bamzai shows how in the early 1920s, when Mahatma Gandhi and Patel were toying with “trusteeship” and not the “abolition” of the princely order in a third of the territorial area of British India, Nehru was inveighing against the feudalism and tyranny of the princes. It was Nehru who “smartly architected” through the All-India States People’s Congress (AISPC), which he founded in 1927, a series of Praja Mandals in the princely states to “spread (the Congress) charter…despite Gandhi’s opposition to active interference”. Several leaders of the Praja Mandals were destined for prominence in independent India—UN Dhebar (Congress president); Pratap Singh Kairon (Punjab chief minister); Giani Zail Singh (president of India). They grew from small-time workers in anonymous corners of the country into front-rank leaders of the nation, having received their political brooding in the Nehru-created AISPC.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Patel stood with Gandhi in their disagreement with Nehru over Congress activism in the Princely States. Nehru, on the other hand, “opposed with all his grit the enslavement of common public in the Princely States”. Thus, in his presidential address to the Lahore session of the Congress in 1929, Nehru underlined that “the Indian states cannot live apart from the rest of India” and moved the resolution on the subject at the Haripura session of the Congress in 1938, reiterated at Tripuri in 1939. “This antipathetic approach remained the bedrock of the future relationship between what Nehru perceived to be an extension of monarchy and true democracy.”

Bamzai notes that “long before Sardar Patel started corralling the Princes…it was Nehru who was at the vanguard of the Congress’ idea of integrating the Princely States by giving the people power…Nehru and Nehru alone defined the rubric of sentiment against the princes”. Adds the author, in the context of the early negotiations for the integration of the states, “While Sardar Patel was conciliatory, Nehru was direct and even brash”. To make his point, Bamzai contrasts Patel’s remarks to a delegation of Deccan rulers who came in July 1946 with a proposal to form a union of Deccan states to preclude full integration into the Union of India with Nehru’s principle argument to the same delegation at a separate meeting with them. Where Patel “averred” that “there was no immediate intention to disturb the present arrangements”, Nehru bluntly opposed “small states being attached to big states…it (attachment) must be in neighbouring provinces (of British India) and never in another (princely) state”.

Bamzai searches assiduously through the record to establish that Nehru “was the progenitor of the idea of breaking the back of the princes”. To this end, Nehru was instrumental in building a popular movement under the auspices of AISPC, over which he presided for 20 years, to demand an end to princely overlordship and integration into a democratic, republican India. Without this movement, carefully nurtured by Nehru over two decades, it would have been the Congress v/s the Princes when the denouement came in 1947. Instead, it became the Congress and the States’ Peoples against the feudal order allied to the Political Department of the departing Imperial establishment. Without the AISPC, and its exertions over two decades, it is entirely possible that the ambiguities in the Indian Independence Act and the dodgy statements and actions of British Prime Minister Attlee and his Secretary of State for India Lord Listowel, the Political Department in Delhi, headed by Sir Conrad Corfield, scheming with the Narendra Mandal (Chamber of Princes), particularly the faction led by the nawab of Bhopal, would have prevailed in establishing some form of “Princestan”. Indeed, Nehru would not have been able to enlist Lord Mountbatten’s active support for a “united and unified” independent India, unless and until the states’ peoples rose against their serfdom. Moreover, Gandhi and Patel would have been proved right in cautioning against interfering with the system of princedom if Nehru and the AISPC had not relentlessly worked among the states’ peoples for two struggle-filled decades. And we would have been left balkanised from the very beginning of our existence as an independent nation.

The instrumentality for doing this was also Nehru’s. He was the one who suggested that before Independence was proclaimed, the Political Department, the guardian of the princes’ interests, be wound up and reconstituted as the States’ Department (Ministry, after Independence). Nehru then requested Patel to head the new department/ministry. Patel in turn persuaded VP Menon, who was planning retirement, to take over as secretary of the ministry. It is this sequence of events that Bamzai describes as “a relay race in which batons were handed over by Nehru to Mountbatten to Sardar Patel and VP Menon—a tough race which they completed in record time”.

The background to these developments (which show Nehru as a statesman) were other developments that showcase Nehru as an activist and agitator. His principled opposition to the maharajas and nawabs and lesser princelings was reinforced by his personal experience of being jailed in Nabha state in 1923 when, accompanied by K Santanam and AT Gidwani, he defied an order by the ruler of Nabha banning their entry into the state. He was sentenced to 30 months’ imprisonment, but after being incarcerated for about a fortnight in Jaito and Nabha jails, he was released when, with great reluctance, he fell in with his father’s and Gandhi’s wish that he sign a bond promising never to enter Nabha again.

That only fired his commitment to freedom for the states’ people in a united and unified India as an inseparable component of freedom from colonial rule. To give practical shape to this goal and meet Gandhi’s insistence that there should be no “active interference” in the affairs of the Princely States until the states people’s awareness had been roused, Nehru founded the All-India States People’s Congress and remained its president till independence brought in its wake the integration of the states into the Indian Union, cuttingly holding to his frank view of the princes that “some are hopelessly backward, some steeped in mediaeval darkness, some are patriarchal, very few maintain good government”.

He avenged himself on the Nabha setback by defying the Faridkot ruler’s order banning his entry into the state. On May 27th, 1946, Nehru tore the order into pieces and “with him at the forefront” marched into the city with “the surging peaceful mass of humanity from across Punjab”. The ruler gave way, and negotiations resulted in a pact between Raja Harinder Singh and Nehru that removed all restrictions on flag hoisting; conducting political propaganda; release of detenus; and an investigation by the chief justice of the state into police excesses. A few months later, after hiccups in the implementation of the accord, the raja “finally announced that a legislative council would be established”.

Nehru, the agitator, then went to “the final frontier called Kashmir” in June 1946. His route took him from Murree to Domel on the Kashmir border where he was subjected to a “murderous assault” by Maharaja Hari Singh’s guards. He brushed them aside and walked to Kohala where he was served with an order under the Defence of Kashmir Rules to leave the state. Ignoring the order, Nehru chose to walk on to Srinagar, 132 miles away. They got as far as Kohala where they were arrested and removed to the Dak Bungalow in Uri that had been declared a jail. Two days later, a telegram came to him from Congress President Maulana Azad, ordering him to return immediately to Delhi, but he had made his point which he explained at a press conference in Delhi on June 25th, 1946:

“Highnesses and excellencies don’t count in people’s eyes in the India of today. Treaty rights, which are dead as doornails, or dynastic rights, which have no value in the people’s eyes, don’t count. It is only human rights that count.”

Meanwhile, Nehru, the statesman-cum-agitator, nurtured his brainchild, the AISPC, from infancy to the kind of adulthood displayed at their Ludhiana session in 1939 and the Udaipur session in 1946, but perhaps most significantly at the meeting of the AISPC Standing Committee on September 19th, 1946 at which a resolution was passed (with Nehru’s presence but in the absence of Patel and Gandhi) covering inter alia the AISPC’s views on all controversial matters relating to the states—ranging from Cochin, Kashmir, Hyderabad and Gwalior to the Eastern States Agencies and Bastar. The states’ people had come of age and negotiations could proceed not on the basis of “trusteeship” [which Gandhi defined as “trusteeship only if they (the princes) become servants of their own people”]—a concept far removed from the absolute dictatorship for which the princes were fighting. This reconciliation of Gandhi’s views with Nehru’s led to the Deccan princelings being advised by Gandhi when they met him in Panchgani in mid-1946 to “meet Pandit Nehru as he was certain that Nehru would guide them in an appropriate manner”. Note: Patel was not yet in the picture. And it was Nehru, not Patel, who wrote to one of the Deccan princelings, the raja of Phaltan:

“We have to first of all examine the whole background—geographical, linguistic, cultural—and then of course the most important the exact desire of the people concerned.”

That Nehru, more than anyone else, was pushing Gandhi and Patel in the direction of abandoning their inclination to “trusteeship” is amply proved by the consistency with which Nehru pushed his case for a total Congress commitment to abolishing the princely order. Thus, in his presidential speech at the Lucknow Congress on April 12th, 1936, “Nehru claimed that Indian Rulers and their ministers have spoken and acted in an increasingly fascist manner. Nehru harboured a pathological hatred for the autocracy…He opposed the sin of autocracy and had a subliminal hatred for the imperial patron-client system that protected the sinner but didn’t condemn the erring Prince”. Then, at the Udaipur session of the AISPC in 1945, Nehru “argued that the princelings were mere mirror images of British Imperialists” and “held that the will of the people was the only paramount power worth recognizing”. “…it was Nehru alone,” says Bamzai, “who displayed enormous hatred against the Princely Order, for he believed that they were worse than the British in subjugating their people”. Perhaps the most cogent reasoning against the Political Department’s plans of restoring sovereignty to the princes on the lapse of paramountcy came from the Nehru-led AISPC Standing Committee in June 1947:

“ …if paramountcy lapses, it cannot mean that the Princes should function as autocratic and despotic Rulers…(Further), (t)he Cabinet Mission’s statement of May 16, 1946 made it clear that the States would form part of the Indian Union and it was not open to any State to leave the Union…To recognize the right of these States (which ‘had submitted to the suzerainty of the Moghul Empire, the Mahratta supremacy, the Sikh Kingdom and finally the British Power’) to independence now is to go against history and tradition, law and practice, as well as pragmatic implications of the situation today…on the lapse of paramountcy, sovereignty resides in the people of the State and the Prince can only be a constitutional Ruler.” The gravamen of the argument was summed up in the slogan, “the people of the States must have an essential voice”.

It was also, at Nehru’s instance, that the AISPC Standing Committee on June 11th, 1947, called for “a new central department” to “discharge the functions of the Political department”.

All this strengthened Nehru’s hand as he walked into the wolves’ den at his meeting on June 13th, 1947, under Mountbatten’s chairmanship, with Sir Conrad Corfield of the Political Department—and succeeded in enlisting Mountbatten’s support in getting Sir Conrad and his department out of running the princedoms. How significant was the Nehru-Mountbatten alliance in bringing about a sea-change in the British government’s attitude towards the lapse of paramountcy is perhaps best illustrated in this extract from Corfield’s memoir, The Princely India I Knew, published in 1975:

“I pointed out to (Mountbatten) that if he used his influence as the representative of the paramount power to persuade the Rulers to enter into political arrangements with a successor government, he would in my view be acting contrary to the spirit of the promises made in the Cabinet Mission Memorandum…Moreover, there could be no guarantee that the limited adherence which was now suggested would not after independence be extended. My protests were of no avail.”

After a fierce showdown with Nehru, in which Mountbatten sided with Nehru (and Jinnah with Corfield), Corfield put in his papers and flew back “home” on July 23rd, 1947. Nehru had succeeded in securing “good riddance to bad rubbish”. The road was thus cleared for the Crown Representative’s famous meeting with the princes two days later, on July 25th, 1947, at which Mountbatten hammered the last nail into paramountcy’s coffin. A “united and unified” India was made possible.

Nehru, as the Prime Minister-designate, then requested Patel to take over the new States Department. In keeping with the principle of devolution, it was left entirely to Patel to decide how to carry forward the work of integration. Nehru, as prime minister, only retained the strategic responsibility to oversee the seamless integration of the Princely States into the Union, the tactical and technical details being wholly entrusted, as in any sound system of governance, to the duo entrusted with implementing the strategic vision—the minister and his secretary. In the same light, the external dimension of integration was retained by Nehru as the minster of external affairs. As such, Nehru continued to be involved in the story of integration but without interfering in the remarkable domestic endeavours of Patel and Menon.

The external dimension came in various guises, principally Pakistan’s efforts to muddy the waters, beginning with Junagarh and extending through Kashmir down to Travancore and Hyderabad. In Junagarh, once the nawab had packed up his dogs but not all his begums, and bankrupted the Treasury, before departing for Karachi, Nehru was in correspondence with his counterpart, Liaqat Ali Khan. He explained to the Pakistan prime minister, in a telegram dated November 9th, 1947, how the Junagarh State Council, represented by its member in charge of the Junagarh forces, Harvey Jones, had approached the Government of India’s regional commissioner in Rajkot with a letter from the Junagarh Dewan, Sir Shahnawaz Bhutto (father of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto), “appealing to the Government of India to take over the Junagarh administration”. The letter further said this “unanimous request” of the Junagarh State Council was “supported by the public of Junagarh”. On this basis, the Indian armed forces were authorised to enter the state without any international opprobrium attaching to the action.

Nehru’s involvement with Kashmir is too well-known to dwell upon here, but what has vanished from public memory is the attempt by the Dewan of Travancore, the wily Sir CP Ramaswamy Aiyar, to use the monazite sands of the Travancore (now Kerala) region, required for manufacturing thorium to make atomic weapons, as the bargaining counter to secure a separate independent state. The story is well worth reading in full, but in this review, I will concentrate only on Nehru getting a resolution passed at the Indian Science Congress in January 1947 “that the state should own and control these minerals—specially minerals required for the production of atomic energy, pointing to the nefarious goings on in Travancore”. He later threatened the use of air power if these shenanigans continued, and sent Council of Scientific and Industrial Research head Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar and Homi Bhabha “to obtain first-hand information about the state’s arrangements with Britain…Sir CP capitulated without a fight” notwithstanding VD Savarkar having urged Aiyar to “declare independence of our Hindu Travancore”.

Although Nehru’s role is less known or, more often, deliberately twisted or obscured, in the police action in Hyderabad, for which Patel had operational responsibility, it was Nehru, as early as June 1948, who made the larger objective abundantly clear: “We have made it perfectly clear to Hyderabad …that ultimately there must be accession”. While a few days later, he wrote to his deputy prime minister that “Military Action should only be indulged in when the Hyderabad government or their Razakkars etc make it impossible for us to desist”, he also had instructions sent to Army commanders that “a strict blockade should be maintained”. On August 29th, he wrote to VK Krishna Menon, that as “Military action becomes essential, we (will) call it, as you have called it, Police Action”. Then on September 10th, 1948, he issued an ultimatum to the nizam: “With great regret we intend to occupy Secunderabad”.

In sum, it was Nehru who had the vision to envisage India without its 565 princes and some 50 lesser princelings; it was Nehru who founded and guided for 20 years the AISPC that raised the states’ peoples against their rulers in the Princely States; again Nehru who persuaded Mountbatten to become his ally in interpreting HMG’s assurances to the princes in such a way that they could not baulk at their integration into the Union of India; Nehru who left the task of implementation to Patel; and Nehru who stood behind Patel as he went about the humongous task assigned to him. Thus, it is Patel’s many and fulsome tributes to “my leader” Nehru that should hold the stage against all attempts, now rife, to portray their partnership as a divided house. Sandeep Bamzai’s contribution to correcting the perspective is both scholarly and heroic.