The Fall of Red Fort

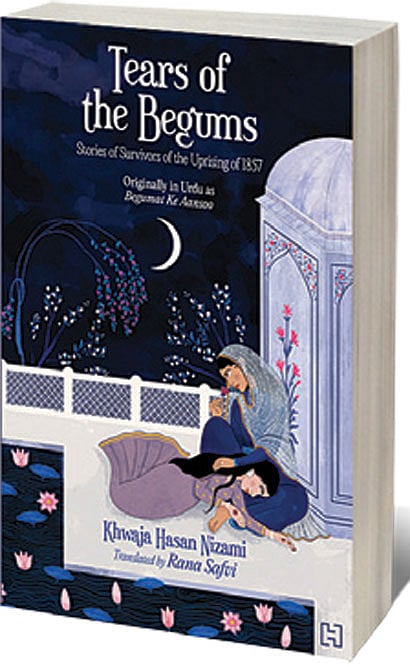

AN URDU ANTHOLOGY comprising oral histories collected from witnesses of the Uprising of 1857 by the 19th-century Sufi, Khwaja Hasan Nizami, in a volume titled Begumat Ke Aansoo is reincarnated in English by Rana Safvi’s earnest translations, Tears of the Begums. Safvi’s translations are diligent: they are spun from three Urdu editions of the volume, the last of which was published by the Khwaja’s heir, Hasan Nizami Sani, in 2008. The English translation makes a crucial architectural intervention with the very first chapter titled, ‘A Picture of the Ghadar.’ It is a bird’s eye view of the Uprising, composed by the Khwaja, which appears somewhere in the middle of the 12-book-edition he wrote about the Uprising. Safvi refurbishes this note as the opening entry in the translated anthology. It recounts the fall of Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last of the Mughals, from which flow the tragedies of the Mughal Empire.

The recorded histories, which comprise the aftermath of the hostile siege of Delhi, are as varied in tone as the Khwaja’s interlocutors. One entry, ‘Bahadur Shah, the Dervish,’ reads like a second-hand memoir, inviting us into the psyche of the former ruler who is seen after the fall as an “enlightened mystic,” resigned from warcraft and to religion. “This country now belongs to God,” the Mughal king says after the takeover, “and He can bestow it on whomever he pleases.”

Another entry attributed to a nameless faqir is inflected by the accents of a different genre. Written by, or perhaps even narrated to, the Khwaja like a parable, it is a reap-what-you-sow story. A nameless faqir, who relays this story to the Khwaja, is disabled by the king’s princes when he reprimands them for hunting. He drags himself to a cemetery with an injured leg wishing a similar fate on his attackers. When the Siege occurs, the princes get their due when they are dragged through the market by the British.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In an anthology that swells with quotidian Mughal voices in the shadow of the British Raj, melancholic characters narrate how the Uprising flattened their grandeur and snuffed their noble careers. There is a prince, for instance, the son of Mirza Babar, Bahadur Shah’s brother, who is rendered anonymous in the annals of Indian history, recast as a cart driver after the fall of the Empire. There is Qimat Beg, a chef at Bombay’s Taj Mahal Hotel who was the son of the emperor and his slave girl. There is a princess who pleads to the photograph of the Vicereine of India, Lady Hardinge, to lift her out of her misery. Her story is deeply disfigured by her melancholy so much so that the Khwaja is compelled to offer an immediate follow-up entry with the “real story.”

As is the lot of any oral history, narratives will be plagued by the inconsis-tency of memory, the over-saturation of mourning and melancholia, the absence of—and need for—annotations. Safvi is an able mediator here. With the authority of a literary scholar, she stands congress with the Khwaja. Safvi tempers the melodrama in his interlocutors’ trauma and offers linguistic, historical, and cultural annotations. With the opening note, especially, she deftly installs a linear poetics of historical storytelling in English that distinguishes her craft from the temporal poetics of the Khwaja’s Urdu. Here is a translator marking her pen and her presence alongside spectral voices of the Khwaja’s interlocutors, contributing to a growing labour of translators to be seen, not as a subset of but alongside the voices they translate.

Deficiencies weaken this translation too. Safvi is not always thorough with the annotations. For readers unfamiliar with the Siege or with Urdu, she is sometimes absent from the footnotes. Nonetheless, it is an important submission to what may become an important text in the canon of Mughal history in English, especially in the last decade or so, which has seen many historians recount the biographies of the Mughal titans. Safvi’s translations bring the everyday into the conversation, animating the miscellaneous who may not have been as prominent as their kin with heavier titles, but whose tragedies were just as pronounced.