The Endearing Paradoxes of Vajpayee

EVERYONE’S LIFE IS awash with contradictions, but there is a case for believing they were the very stuff that defined Atal Bihari Vajpayee. In her lively and absorbing biography of “India’s most loved Prime Minister”, Sagarika Ghose attempts to come to grips with these paradoxes, laying them out, trying to square them up, and leaving them unresolved when no explanations are possible— the last, quite correctly. It is biographical conceit to assume that something as complex as humans and their behaviour can be fully understood.

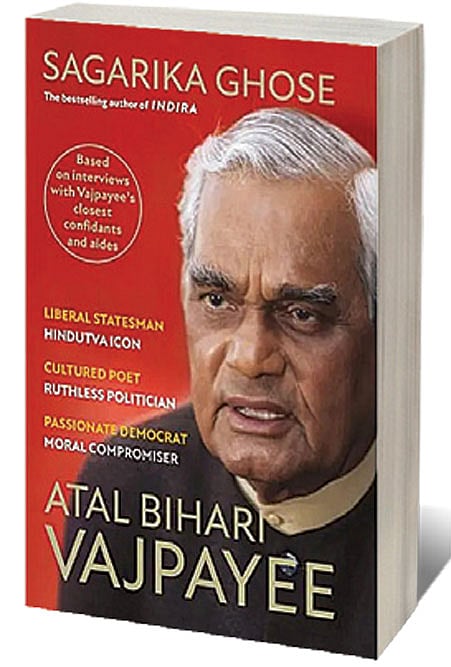

The book’s cover flags three of these incongruities—Liberal Statesman/Hindutva Icon, Cultured Poet/Ruthless Politician, Passionate Democrat/Moral Compromiser—but one could add many more to the life of a man who was never easy to pin down. As the biographer of a person who died only four years ago, and as a journalist who covered the Vajpayee era, it was perhaps natural that Ghose would use the profusion of living witnesses to unravel this enigma of a man.

Biographers who prefer to know their subjects only from written record like to maintain that their accounts are more detached and ipso facto more objective. But Ghose’s purpose is different. Hers is not to render Vajpayee in a chronological or accumulative manner (there is not much on his early years, for instance). Nor is it to write in an impassive non-opinionated way. She is critical when she feels the need to be. (“Appallingly, on Gujarat, Vajpayee the calculating politician prevailed over Vajpayee the constitutional moralist.”) And there are words of praise for such traits as his “parliamentary spirit”, his ability to forge personal relationships across political divides, and his engagement with Pakistan and the people of Kashmir.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

So, who was Vajpayee? Ghose doesn’t pose the question explicitly. But it seems very much at the back of her mind as she grapples with the changeable ways of her “slippery hero”, one day a “moderate” and the next day a “hardliner”, endowed with a chameleon-like ability to meld with the shifting political mood. The picture that emerges is of a man who, for all his virtues, was a thoroughgoing politician, driven by a sharp ambition that lay concealed behind a cultivated mist of charismatic unworldliness. He was not above being ruthless to those he considered political rivals. Vajpayee played a pivotal role, for instance, in the downfall of Balraj Madhok (who went on to accuse him of an ugly conspiracy). And he cut down KN Govindacharya, who was blamed for describing Vajpayee as a mukhauta (mask), a charge the LK Advani camp follower and party ideologue denied, strongly and repeatedly.

Ghose’s treatment of Vajpayee suggests he was anything but a mukhauta, at least not in way the expression was used to describe him. His moderate face was not something he donned for the sake of others, nor was it a part of a BJP ploy to appear middle of the road or politically temperate. The various faces he wore (or the masks he donned, if you must) were those he chose to. His discomfort with what Ghose calls the uber-Hindutva groups (such as the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and the Bajrang Dal) was real. His disapproval of the shape the Ram Janmabhoomi movement was taking and his belief that Narendra Modi must resign following the Gujarat riots weren’t simulated either.

When he did fall in line with views he opposed, it was because he knew, as canny politicians do, that you only pick the battles you can win. As for his ability to change tack and obliquely defend what he once seemed to oppose, it was built around his proclivity to speak in generalities, with a strategic ambiguity that helped to at least partially obscure the contradictions.

The dizzying arc of his political life—which Ghose notes almost spanned the entire length of post-Independence India since he started contesting elections as early as 1955—is a story of many things. It is a tale of how Jana Sangh lived for decades in the shadow of Congress, particularly under the towering presence of Jawaharlal Nehru. The 1960s saw BJP entering into an electoral understanding with other parties in the cause of anti-Congressism, which developed into a broad and ideologically incohesive coalition against Indira Gandhi in the 1971 general election. This, in turn, prepared the ground for Jana Sangh to forsake its identity by merging into the Janata Party after the Emergency was lifted, only to reorganise as BJP in 1980.

It was during the mid-eighties that the Sangh stepped up the Ram Janmabhoomi campaign. It was spurred, among other things, by Rajiv Gandhi’s capitulation on the Shah Bano controversy and his attempt to compensate politically for this by going along with the order to unlock the Babri Masjid for Hindu prayer. It was for this brief period, something like a decade, that Vajpayee’s authority was diminished, with Advani (and others such as Murli Manohar Joshi) growing more assertive. But the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1991 doused some of the hot-headed fervour the movement had generated, and only a couple of years later, BJP stared at defeat in Uttar Pradesh and elsewhere in the north.

In late 1995, Advani suddenly announced that a marginalised Vajpayee would lead BJP as its prime ministerial face in the next election. Ghose attributes this to Advani’s “political astuteness” and a recognition of his own limitations. But it was also a brave decision, taken in the face of a disappointed RSS and other sections of the Parivar. It was also a tacit acknowledgment that, in the prevailing political circumstances, Vajpayee’s ability to build coalitions and reconcile differences were needed once again. Ghose describes him as a “terrific listener”. She also regards him as a liberal in the sense that he was open to forging close friendships with people he strongly disagreed with—a virtue that is not merely missing, but also frowned upon in these terrifyingly polarised times.

His first stint as Prime Minister lasted only an embarrassing 13 days, but Vajpayee was back, for one year the second time, going on to complete a full term after winning the post-Kargil election in 1999. Almost a full term is more accurate. Come 2004, Vajpayee was reluctantly persuaded by his inner circle to advance the election. It seemed logical given BJP’s huge wins in the December 2003 State Assembly elections (the so-called semi-final) and an economy that was booming with double-digit growth. But an overconfident party failed, principally because it had lost the DMK (which had pulled out of the NDA well before the election) and did not anticipate the TDP’s dismal performance in Andhra Pradesh. It also performed poorly in Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat, but these setbacks were partially offset with gains in other states.

It is here that Ghose begins her account, with the story of loss. It is not clear why she does so, but it is possible she believes that this was the most dramatic swing in Vajpayee’s career. Written with a keenness to engage the reader, with generous sprinkles of anecdotes and political insight, the book paints a convincing portrait of a man—his virtues, his faults, the compulsions that moved him to act, and the constraints that stayed his hand. If the book leaves one feeling there is still more to the man, it is hardly the author’s fault. Blame it on the conundrum called Vajpayee.