The Diplomat Doctor

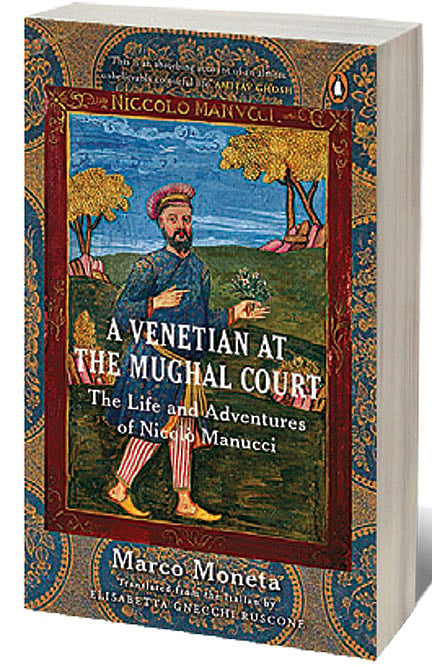

IT’S HARD TO believe Marco Moneta’s A Venetian at the Mughal Court is a work of non-fiction. This remarkably well-researched biography of Italian traveller, writer, diplomat, and court doctor Nicolò Manucci (1638–1720) has the irresistible magnetism of fiction. Teeming with action and populated by a colourful cast of characters including emperors, Viceroys, sultans, merchants, missionaries, ascetics, Sufis, doctors, adventurers, rebels, and rogues, Manucci’s life in Mughal India makes fascinating reading. Manucci lived in India for over 60 years—between 1656 and 1720. He was a man in the thick of things; an articulate and alert witness to critical events of the time.

Moneta makes good use of Manucci’s own Storia do Mogor, weaving in several passages of interest from Manucci’s book into the biography. Storia do Mogor, written decades ago, is a first-hand account of Manucci’s experiences in the Mughal Empire, which coincides with the reigns of Aurangzeb (1658-1707) and Bahadur Shah I (1707-1712).

A Venetian at the Mughal Court reels you in right from the start when “greatly wishing to see the world”, the teenaged Manucci hops on a ship in 1653 in search of adventure. English nobleman Henry Bard, Viscount of Bellomont, takes the penniless boy under his wing. The Viscount is headed to Persia in the hope of soliciting the Shah’s help for exiled Charles II. Manucci travels with the Viscount across the Ottoman Empire to Esfahan where he manages to learn Persian as well as court protocol. Later, the two head to India (Surat) with plans to move on to Delhi. When Lord Bellomont passes away, 18-year-old Manucci is left to fend for himself in an alien land.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Despite setbacks, Manucci not only managed to survive but also be at the centre of “almost all events that made history” in his time. He “took part in the battles that decided the fortunes of the Mughal empire; he witnessed the rivalries, intrigues, jealousies…and crimes by Mughals and Europeans, he visited and lived in courts, palaces and centres of power.” He went on to work as a soldier, a diplomat, and as a court physician to Aurangzeb’s son Shah Alam, undeterred by the fact that he had little or no formal education.

A keen observer of the human race, Manucci also chronicled the history of the Mughals and the socio-political churnings of the time. He learnt Turkish, Persian, Urdu, French and Portuguese. A man of “extraordinary character”, he rose from obscurity to a position of influence thanks to his keenness to learn and adapt, and his gift for being at the right place at the right moment. Manucci did express the desire to return to Europe more than once, but his attempts to go back were never fruitful. Eventually, “having become accustomed to the climate and the food of India”, he settled down in Madras and Pondicherry.

Moneta peppers the book with the larger-than-life quality of Manucci’s exploits as well as an impressive array of historical facts. The result is a rich history of Mughal India, written in an engrossing and easily accessible style. The Italian-English translation by social anthropologist Elisabetta Ruscone is seamless. Manucci comes across as a flesh-and-blood character, not a hero mothballed in the distant past. The people he interacts with—whether kings or commoners—emerge as three-dimensional figures who are bound to capture the reader’s attention.

This book is essential reading for modern readers for many reasons. It paints a clear picture of the workings of the Mughal court and sheds light on the transformation of the European presence in the subcontinent at a defining moment in history. Manucci’s experiences at the courts of the Mughals and the sultans of the Deccan, in Delhi and Lahore, in the missions of Agra and Goa, on the battlefields, and his many journeys by foot and on horseback across the length and breadth of India are not to be missed.